This is the third in a blog series about Raw-Milk Cheese. This section focuses on some of the cultural forces waging war with the federal government over raw-milk regulations. Missed last week’s post on the health benefits of consuming cheese made from unpasteurized milk? Check it out!

THEY BURIED HIM AMONG THE KINGS BECAUSE HE

HAD DONE GOOD TOWARD GOD AND TOWARD

HIS HOUSE

– Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, Westminster Abbey

Will Studd experienced every cheesemonger’s worst nightmare—he lived to bury his own Roquefort. In 2003, he was ordered by the Australian government to destroy an 80 kg shipment of the famed blue cheese he had received fresh from France. Studd, who described Roquefort as the king of French cheeses, fought tooth and nail to reverse the regulation that forbade cheese made from unpasteurized milk. Proving at the very least that the laws surrounding cheese were crystal-clear, the government ordered that he bury the cheese in refuse. Taking the cheese off of death row, Studd wrapped it in the French Tricolore and transported it by hearse to its grave, where a dump truck was waiting to obliterate it from our pantries but not from our memories. In a painful reversal, the Australian law was changed to allow Roquefort only two years later. Neveretheless, as Studd put it in an interview for culture, “There are times when standing up for principles of choice can be seriously risky and emotional, but if you don’t take the risk you get nothing at all.”

This is only the starter-culture for raw-milk activism, a world that can only be described as bizarre. From burials to SWAT raids, udder-anarchists to something called “microbiopolitics,” raw milk seems to bring out the strange in us. Suit up, for we are about to airlift into the war-torn swamp of the raw-milk debate, a battleground that is cultural, political, academic, and religious all at once.

Setting the Stage: Raw-Milk Cheese Makes Strange Bedfellows

The people you might meet at a raw-milk rally fall into two groups. The first type could be described as “crunchy.” These neo-hippies eat organic, compost their toenail clippings, and have Bernie! shirts from before you were born. The second type might have been called Tea-Partiers in 2010, but for the sake of relevancy we can just think of them as libertarians (let’s just say that these people have made politically inspired purchases at costume stores at least once in their lives). As someone who lives on the border between New Hampshire and Vermont, I am familiar with these types—they even have separate states! For them to come together on a political issue is uncommon, but cheese can be miraculous at times.

The motivations surrounding this convergence are tangled and fascinating. In a 2010 raw-milk rally on the Boston Common, the predominant demographic was the Libertarian group, and the prominent theme was individual rights. Activist Max Kane was most explicit with his notion that we have “every right to eat the natural foods of the earth.” He went on the make the oddly pro-choice claim that “the only way another person can tell you what you can and can’t eat is if they claim control of your body.” This contrasts with the communal rights claimed by the crunchy group. Since most raw milk originates on small, non-industrial farms, and since it mostly is obtained through milk-sharing and food clubs, the rhetoric tends to hinge around the strength of communities and the primacy of community responsibility over government regulation.

Splitting the difference between these competing justifications is Vernon Hershberger, who claimed that pasteurization laws violated his religious freedom after he was arrested for the unlicensed sale of raw milk. The Bible tells him to share his food with his brothers and sisters (meaning his unpasteurized cheese and his customers). Hershberger managed to hit his marks both for personal liberty and community responsibility. Hershberger was ultimately exonerated.

The similarity in vision between the two groups brings into question their purported differences. Both have a certain longing for a rosy agrarian past, where Farmer Joe could trade a bushel of apples for Farmer Bob’s hen and call it a day. Raw milk has a special symbolic significance, a purity even. In an interview for a 2012 New Yorker piece on raw milk, two-Michelin-star chef Daniel Patterson identified a sentimentality to the raw-milk food he served. His upper-crust clientele sought nostalgia through food, and “raw milk is a primary touchstone of that sort of agrarian, old-fashioned way of life.” A common slogan of the raw milk movement is “Raw Milk Heals.” This applies to the purported health benefits, but it also refers to a sort of regressive societal healing. Raw milk is often described as tasting “alive” (how something other than, say, a squirming octopus can taste alive is beyond me). Masked in this flavor profile is a societal critique: the flavor of industry/technology is unpalatable to activists, especially in contrast to a more life-affirming system.

Dairy Farmer Mark Mcafee describes the taste of pasteurized milk as “dead and burned.”

Photo Credit: Mark McAfee, Founder of Organic Pastures Dairy by Take Back Your Health | CC

An Anthropologist’s Take

In the mid-20th century, Michel Foucault termed the phrase “biopower,” and introductory philosophy classes have never been the same since. For those of you who still forget which letters to pronounce when talking about Nietzsche (it’s the ‘N,’ ‘ie,’ ‘ch,’ and ‘e’), biopower is a theory surrounding surveillance and large populations. The basic idea is that an organization (i.e., a government) can control its citizens through monitoring their actions. Heather Paxson, MIT professor and author of Life of Cheese: Crafting Food and Value in America, came up with the term microbiopolitics for the ways in which people are controlled by monitoring their microbes. This applies specifically to raw-milk cheese, whose microbes have been put under intense scrutiny.

Paxson discusses Pasteurians and post-Pasteurians, intimidating terms for germophobes and their friends who tell them to chill out. The idea here is that, after Pasteur figured out how to make food safer, people started obsessing about getting the safest food possible. This is how “germ” became a dirty word; people were so concerned with maximizing sterility that anything microbial became suspect. Some people have started resisting this idea. Food shouldn’t be subjected to constant, neurotic concerns over pathogens. It should be celebrated as a source of health, not condemned as a possible infectant.

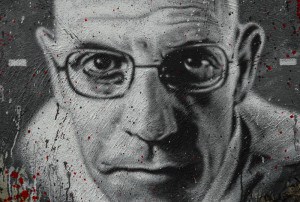

Michel Foucault pioneered theories in surveillance and “biopower.”

Photo Credit: Michel Foucault, Painted Portrait by Thierry Ehrmann | CC

Post-pasteurians emphasize the power of microbes to improve health. Rhetoric about natural, wholesome, or organic food expresses the idea that people are willing to swallow some risk (literally) in the pursuit of self-betterment. More importantly, they seek to reclaim eating as an individual choice, not a regimen laid out by medical professionals and bureaucrats. This seems to be the real rub—maximized hygiene isn’t just the norm, it’s the law. Why should my choices about what I eat matter to the government? Microbes shouldn’t be the sole purview of officials. This is the logic used by raw-milk activists. Cheese is a composite of several living organisms, and eating it raw proves that people aren’t controlled by their fear of germs and don’t accept the governmental obsession with micro-organisms.

Can Lysteria be Good for You?

August 3, 2011, was a bad day for James Stewart. It started out a day like any other: stocking his meat cooler with Bison testicles, replenishing his camel milk supply, preparing to take his 9k in “fruit money” to the bank. This was, of course, before an LAPD SWAT team showed up at his door with federal agents, ready to seize it all and flush 800 gallons of raw dairy down the drain. Stewart ran the now-infamous uber-organic specialty store called Rawesome. After agents collected undercover information about his unlicensed traffic, they showed up in full force to book him. Bail was set at $123,000.

Rawesome catered to an upscale clientele who demanded the extreme of freshness and organic. Rather than the Vermont hippies campaigning for the farm next door, this demographic is chic-crunchy. The question of “rights” seems like a distant populist whine—who would have thought the FDA could shut down the specialty store where John Cusack’s chef exclusively shopped? This caste focuses primarily on health, and their approach is alarming.

Rather than enlightened post-Pasteurians, Rawesome clients were willing to sign away liability for any pathogens they contracted, and you have to figure that risk was pretty darn high. Moreover, employees demonstrated not only nonchalance toward these deadly microbes but active desire. After the USDA discovered Lysteria in samples taken in 2010, they consumed those samples anyway! Paxson echoes this: in extreme examples of the organic-minded, there isn’t any distinction between good and bad bacteria. Rather, “‘the naturalness’ of raw milk accounts for its healthfulness.” In this view, pathogens become good things because they are natural.

I interpret this as an extension of the Pasteurian obsession for hygiene. Rather than an irrational fear of germs, extremists in the raw-milk community have an irrational fear of chemicals (or anything deemed not natural) or the government. Something can only be good insofar as it lacks those elements, and it is bad if it possesses them. This sort of mindset is why I was interested in this topic in the first place—if we can accept a balanced and level-headed approach to raw-milk cheese, perhaps we can learn to get over these bizarre prejudices. Just as we shouldn’t cower in front of our germs, neither should we cower in front of our toxins, or in front of our governments, or in front of our corporations. The world isn’t out to get us, especially not through our cheese.

Tune in next week for the final installment, in which I actually eat raw-milk cheese, contract e. coli, and perish!

Feature Photo Credit: Raw Milk Rally Downtown LA by Ann Marie Michaels CC