This is the first in a blog series about Raw-Milk Cheese. This section focuses on the science behind the risks of consuming unpasteurized cheese.

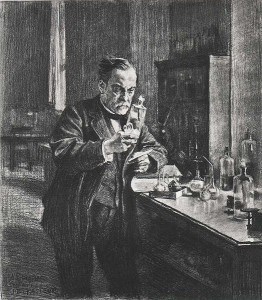

In 1856, Louis Pasteur discovered that fermentation was caused not merely by chemical reactions but by the work of a living organism, yeast. From this simple revelation, the way we conceive food underwent a fundamental shift. Nourishment was no longer inert or passive but living, diverse, and dangerous. Though Pasteur illuminated our understanding of disease and microbiology, to this day people choose what they eat not because of lucid conceptions of microbiology but because of unseen, phantasmal agents of evil. We are haunted by words like “germ” or “toxin.” People develop powerful, fundamental beliefs about what they should eat, but often rationales fail to rise above the vaguest notion that what we’re eating could be eating us.

Pasteurization involves heating a substance in such a way so as to kill harmful microbes. It also has the side effect of killing many other not-so-harmful bacteria, many of which count in the flavor profile of milk and cheese. In 1948, the first statewide requirements that milk be pasteurized were legislated in Michigan. Often hailed as one of the greatest contributions to food safety in modern times, milk fell from its status as a primary carrier of food illness. Interstate sale of unpasteurized milk was banned in 1987 by the Food and Drug Administration, but individual states were still empowered to regulate pasteurization for products that didn’t leave their borders. To this day, the topic of milk pasteurization and its role in cheese making is hotly contested. Through this cheesy fog-of-war, it can be difficult to tell what is safe and what isn’t. Should you eat raw cheese? After sifting through the available data for the United States (sorry Europeans—your continent is a whole other can of worms) my answer is a firm, resounding maybe.

First the bad news. In the period from 1993–2006, the Center for Disease Control reports that 60% of all dairy outbreaks (73 total) came from unpasteurized sources. An outbreak is defined as a food illness that two or more people contract from the same product. This statistic is worse in context; the 2003–2004 and 2005–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys reported that less than 1% of milk drinkers drank raw-milk. That means that—for milk—incidence of outbreaks was 150 times greater on a per gallon basis.

At a closer look, though, things get a little complicated. The CDC report on cheese-related outbreaks from 1998–2011 shows similar data on a surface level. Despite a vast disparity in total consumption, outbreaks levels are roughly the same, with 38 outbreaks for unpasteurized cheese and 44 for pasteurized cheese. However, not all unpasteurized cheeses are created equal. A report on cheese compliance from the Food and Drug Administration shows a rosier picture. After testing 17,324 unpasteurized cheese samples, incidences of pathogens in domestic cheeses seemed quite low. E. coli occurred in 0/478 samples in 2004, 0/317 samples in 2005, and 0/210 samples in 2006. Listeria occurred in 6/412 samples in 2004 (1.5%), 2/286 in 2005 (0.7%), and 2/163 in 2006 (1.2%). Salmonella occurred in 3/502 samples in 2004 (0.6%), 2/329 samples in 2005 (0.6%), and 0/211 samples in 2006. The study finds this data encouraging; not only are the rates well below those of other European countries (which generally hover around 5% occurrence), but in general they trend downward, showing greater regulatory compliance over time. Note that this study draws data from cheese operations with a history of microbiological contamination, and the samples themselves are the “likely suspect” cheeses as qualitatively determined by the inspectors—they are looking for the worst of every batch.

Single-state outbreaks attributed to cheese, by state and pasteurization status, 1998-2011

Data from Centers for Disease Control

Why the discrepancy? Well, remember that while the FDA is assessing the product itself, the CDC is only concerned with the end result: disease outbreak. That means that some questionable outbreak sources are glossed over by the CDC. It seems the culprit is primarily foreign or imported cheeses. Both studies identify them as the main cause of pathogens. In fact, in the CDC study, half of all unpasteurized outbreaks were attributed to soft Mexican cheese (queso fresco). The study also states that 15% of unpasteurized outbreaks happened because of illegal operations, including one sketchy sounding unlicensed street vendor (note, if you hadn’t figured this out, don’t buy your fresh cheeses out of unmarked vans). If you look at only legal domestic cheese, the number of outbreaks drops from 38 to 16. The CDC further says that many instances of pathogens in cheese (especially salmonella) are caused by environmental contamination from other animals and not the raw milk itself in the cheese. While this is an intrinsic problem of raw-milk cheeses, which are normally made on small farms, it is a problem that can be targeted and mitigated by regulation. Some outbreaks were caused by ignoring rules, specifically the legal minimum of 60 days for ripening. These too could be curtailed through regulation.

It’s worth noting that raw-milk cheese is safer than raw milk, which contributed 82% of milk-related outbreaks from 1993-2006. Indeed, the FDA study identifies a relatively high presence of S. aureus in raw milk and raw-milk cheese, but the CDC only reports outbreaks for raw milk. This is likely because S. aureus is easily outcompeted by starter cultures. These bacteria normally responsible for flavoring cheese are a health boon—they tend to have a pacifying effect on pathogens, making cheese safer than milk as a rule.

In a small cheesemaking operation, it is much easier to find and target potential contaminants. Anthropologist Harry West points out that, since these cheesemakers often rely on regional reputation, they work much harder to ensure food quality and safety. Though the US has gotten much better at industrialized food production since Upton Sinclair, making food on such a scale bears unique risks. The CDC reports that, for pasteurized cheese outbreaks, 35% of contaminants were introduced by bare-handed contact by a handler/worker/preparer, 31% by handling by an infected person or carrier of pathogen, 23% by storage in contaminated environment, and 19% by glove-handed contact by handler/worker/preparer (in many cases there were multiple sources of contamination). These causes affected 0% of unpasteurized cheese. This isn’t to suggest that it is better to have your deadly pathogens come from more wholesome, less dehumanizing sources. It should suggest that the model of large scale food production has its own distinct flaws.

So if you eat raw-milk cheese, there is a higher chance you will contract a pathogen than if you eat pasteurized cheese. That risk is probably lower than what is purported by the CDC, especially if you buy through legal, domestic sources. You certainly shouldn’t eat it if you are too young, too old, or too pregnant. But if you do your research, understand what the risks are and why, and—most importantly—accept those risks as real and valid, raw-milk cheese seems viably safe.

Next week, I’ll continue this line of thought with a look at the benefits of raw cheese both real and imaginary. Stay posted for the juicy details on whether raw milk can cure what ails ya.

Why is it that unpasteurized dairy has been such an issue in the US. I have lived in places where people have been eating raw milk cheeses for generations pretty much without incident? At this point the truth is that the rate of death and illness caused by the following legal activities, those being cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption, FAR outweighs the risks of eating raw milk cheeses. The Americans ought to get it together when it comes to this. If they can’t learn how to do it themselves then at least allow the import of these cheeses from people abroad who know what they are doing. There is just nothing to say when it come to raw milk cheeses. As far as I am concerned pasteurized cheeses will sadly always pale in comparison to their much funkier raw counterparts…

The CDC study had several other serious flaws.

For example, when it could not be determined if the milk was raw or pasteurized, it was assumed to be raw. Of course all legally produced cheeses would have been clearly defined as raw or pasteurized, therefore shunting the indeterminate ones into the raw category simply added most of the “bathtub cheeses” into the raw category.

Also, and this may be the most telling flaw of all, the study covered a period of time when there were something like 16 billion pounds of milk consumed in the US, resulting in just a handful of outbreaks. (I don’t have a copy of the study with me, here in my North Forty pasture, but the statistics are in either the abstract or the intro) The morbidity stats on this tsunami of milk are so low as to be statistically insignificant–you might be ten times more likely to be killed in a car crash on the way to the store tham the chances of gettimg sickened by a dairy product.

Now if you were one of the unlucky ones who got sick, this is still bad news, but frankly, the most obvious conclusion to be drawn from the CDC study is that all dairy foods, raw or pasteurized, are amongst the safest foods that you can eat.

This is clever, entertaining, and interesting!