A cousin of cheddar, Colby cheese is mild, sweet, and elastic, with nutty, milky notes. Widely considered to be one of America’s first original cheeses, Colby is in a class all it’s own: the recipe has been around for nearly 150 years, and it has been wildly popular for nearly as long. Its mild flavor makes for endless pairing opportunities, and is the perfect addition to your table.

Origin

Colby was created by Joseph F. Steinwand in—where else?—Colby, Wisconsin. Invented in the late 1800’s, Steinwand created Colby by tweaking a traditional cheddar recipe, which resulted in a milder, sweeter, and immediately popular cheese. Originally, the cheese was made in tall, cylindrical shape called the “Longhorn” shape, pressed into 13 pound horns, and waxed before sale. Today, Colby is most often made in large blocks before being cut and waxed. The semi-hard cheese is made from cow’s milk and should be eaten young (four to six weeks is recommended), as aged Colby becomes dry and cracked.

“Joseph F. Steinwand in 1885 developed a new and unique type of cheese. He named it for the township in which his father, Ambrose Steinwand Sr., had built northern Clark County’s first cheese factory three years before.”

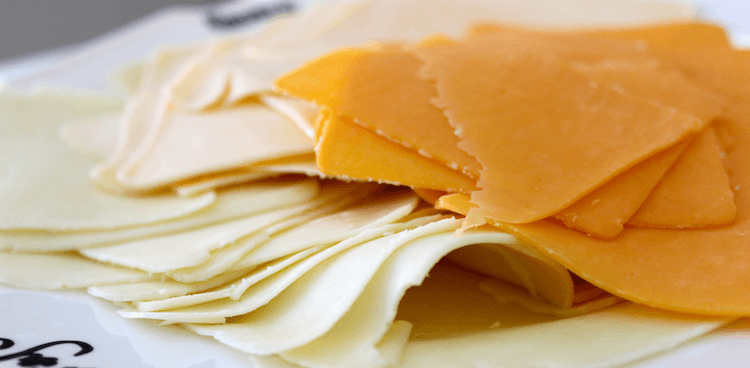

Photo from New England Cheesemaking Supply Co.

Colby—originally called Colby Swiss Cheddar—is a rindless, golden cheese with a springy, firm consistency. It has more moisture than its cheddar cousin, and a more open texture, dotted with small holes. These natural holes are an integral part of a true Colby wedge, and have been a central point of debate for Colby producers. In the 1970’s, Wisconsin’s Department of Agriculture amended the required characteristics of Colby, saying “The cheese may have evenly distributed small mechanical openings or a closed body.” The addition of the term “closed body” meant that modern producers could take shortcuts in the traditional process, and instead label a cheese that resembles a mild cheddar as a Colby.

How It’s Made

Colby starts out like any other cheese: milk is heated and a culture is added to separate the whey from the curd. While cheddar undergoes the “cheddaring” process, stacking the curds so they can knit together under their own weight, Colby follows a different approach, known as the “washed curd” process.

After the curds and whey have separated, most of the whey is drained off, and fresh, cool water is added to the curds. This has two main effects on the finished product. One, it lowers the temperature of the curds, which gives the cheese a higher moisture content. And two, it rinses the curds free of milk sugars, which gives lactic bacteria less to process and results in a lower acidity for the final cheese. This gives the cheese a soft, elastic feel and sweeter flavor. After the cheese has been rinsed, it is salted, pressed, and allowed to dry out before being dipped in wax to properly seal and protect the block.

Authentic Wisconsin Colby cheese. Photo from Wisconsin Cheese Talk

How to Eat It

Because of its mild flavor, Colby is not often used in cooking. Instead, slice, grate, or cube the fresh cheese into nearly any dish for a light lactic tang and toothsome bite.

- In a glass: To avoid overpowering the cheese completely, opt for a milder wine like Chardonnay or Zinfandel, or play off Colby’s nutty flavor with a red or brown ale.

- On the cheeseboard: Slightly sweet sliced Colby balances salty olives or pickles nicely, while whole-grain mustards add a vinegary kick to the low-acid cheese.

- In the kitchen: Colby melts beautifully, but be carefully not to drown the cheese with aggressive flavors. Try it in a classic mac ‘n’ cheese for extra elasticity, or have it stand in for a too-sharp cheddar in a diner-style sandwich.