There’s been a lot of debate about the safety of raw milk cheese versus unpasteurized cheese. Sometimes the arguments from both sides are overwhelming. Is pasteurization necessary? Beyond that, what the heck is pasteurization? Since I was a kid, I vaguely knew that milk was pasteurized to make it safe to drink, but I couldn’t tell you much beyond that. So let’s dig into the history of pasteurization to see where it came from, what it’s all about, and why it’s still happening today.

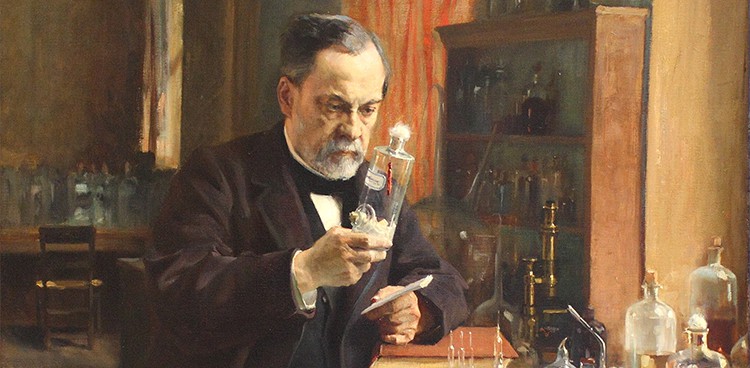

To do that, we have to go back to nineteenth-century France and the work of Louis Pasteur. As you probably guessed from his name, Pasteur invented the process of pasteurization. But he did not initially set out to look at milk. He was interested in the preservation of beer, wine, and vinegar like any good Frenchman should.

His goal was to figure out what fermentation was and why it happened. One of his targets was lactic fermentation—how the sugar in milk turns to acids. The prevailing theory in the 1850s was that fermentation was a chemical reaction that had no biological cause. Pasteur’s work discovered something quite different. He made the argument that microorganisms, or bacteria, caused fermentation’s chemical reactions to happen in the first place.

In the simplest terms possible: Pasteur discovered that bacteria causes fermentation. In the case of milk and lactic acids, bacteria in the milk made it curdle more quickly. By eliminating the bacteria in the milk, it could be preserved longer. The easiest way to get rid of the bacteria was to heat the milk. Thus began the pasteurization process. The FDA currently defines pasteurization as heating milk to a temperature of 145 degrees F and maintaining it for at least 30 minutes. Milk can also be heated to higher temperatures for shorter amounts of time.

Milk wagon in front of the W.B. Hage Creamery in San Diego, 1895

Why did it matter how long it took milk to curdle? All milk before pasteurization was raw milk, which can contain some serious bacteria. In the US, people moving to urban areas in turn caused serious problems. Milk transported from the countryside to the city would spend a good deal of time at higher temperatures, making it a target for bad bacteria. Milk produced closer to the city often had cows in cramped and unsanitary conditions, making the milk full of bacteria from the get-go. The number of people getting sick and dying from consuming contaminated milk triggered a nationwide discussion. The Illinois Supreme Court sums in up nicely in a statement from 1914: “There is no article of food in more general use than milk; none whose impurity or unwholesomeness may more quickly, more widely, and more seriously affect the health of those who use it.”

Despite the health concerns milk presented, not everyone embraced it wholeheartedly. Because milk regulations did not dictate that milk must be pasteurized, many producers avoided taking on the cost of buying the equipment they would need to pasteurize. Not that it mattered much—he general public thought that milk contaminated was more because dairies were lazy and if they would just maintain standards of cleanliness, their milk would be safe to drink.

The large dairies that were able to buy pasteurization equipment exposed their milk to more people in the production process, which worried the public. They thought that dairies who adopted pasteurization then cut out other cleanliness measures to save on costs. The Women’s Municipal League in Boston had a solution: they instructed housewives to pasteurize their milk at home.

A panel on a Louis Pasteur monument that we’re pretty sure is Death menacing some adorable dairy animals. Photo Credit: “Louis Pasteur monument…” by Kiev.Victor | Shutterstock

Finally, some producers didn’t properly pasteurize their milk. They exposed it to high temperatures between 120 and 180 degrees F but not for the proper length of time. This helped preserve the milk but didn’t ensure it was safe to drink, leading The Jersey Bulletin to proclaim in 1908: “Many mothers are cheated into the belief that they are getting a safe milk when they buy what is described as commercially pasteurized milk. Such milk should by labeled NOT Pasteurized. It is a humbug and a fraud, for it has not been pasteurized at all.”

In 1921, the federal government was still advising people to pasteurize their milk at home. The US Department of agriculture actually released a pamphlet that suggested people eat cheese as a safer alternative! It took a lot of time and struggle to adopt pasteurization in the US, but the process did have an impact. In 1938, disease outbreak caused by milk were about one-quarter of all outbreaks caused by food and water. That number is mind boggling to the modern reader and goes to show why pasteurization and safe milk was such a huge concern.

Feature Photo Credit: “Louis Pasteur in his laboratory” by Albert Edelfeldt, 1885