People tend to focus on what they can see: the big stuff. But one of the most abundant populations on earth is too small for us to see: the teeming lives of bacteria. Bacteria are more numerous than any other organisms on earth. There are probably more than a million bacterial cells on the tip of your finger right now. But don’t freak out! We need bacteria. They reside in our digestive tracts and break down compounds we can’t digest (and in the process give us vitamins our bodies can’t make for themselves, like vitamin K). They also work cooperatively with bakers, brewers, and cheesemakers to give us bread, beer, and cheese. Most of the time, bacteria are our friends.

This is not to say that all bacteria plays nice. Listeria monocytogenes has been the culprit of many a dairy closure in the past few years. This strain is highly resilient and can’t always be killed by conventional sanitizers. It also has a significant case-to-death ratio, dwarfing that of the more well known Salmonella. According to Catherine Donnelly, a professor in the Department of Nutrition and Food Science at the University of Vermont, the percentage of cheeses that test positive for Listeria each year are slim to none; this bacteria strain is usually environmental, found on floors, drains, and stainless steel surfaces. And when there is an outbreak, it’s due to unmonitored imports that don’t fall under domestic regulation.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), charged with keeping Americans’ food safe and free of contaminants, has always been afraid of these menaces, especially with regard to the dairy industry. The results are laws and regulations concerning pasteurization and the Current Good Manufacturing Process, which demands that all surfaces in food production be adequately cleanable and maintained in good working condition. But with that kind of language, much is left open to interpretation in the way of permissible tools and practices–like wooden shelving, for example.

Bacteria convert carbohydrates into gasses, forming the holes you see in a Swiss-style cheese. / Photo Credit: Pinprick via Compfight cc

This is all to explain why the cheese world was in such a panic this week. Statements from the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition letter to the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets’ Division of Milk Control and Dairy Services ended up posted on cheese blogger Jeanne Carpenter’s website. These statements seemed to threaten to end the use of wooden shelves in cheesemaking, citing worry that the material was too unhygienic and had too much risk potential for the growth of Listeria.

culture watched the story unfold, and listened to the outcry of both cheesemakers and cheese lovers over the harm such a ban would do to the American cheese industry. In fact, some worried that imported cheese using wood shelves for aging would not be allowed into the country under a joint interpretation of the Food Safety Modernization Act, the act cited in the letter. The FDA quickly issued a statement on Tuesday and then an official “constituent update” on Wednesday night. The final update stated that wood had not been banned, though they continued to say that “the communication was not intended as an official policy statement, but was provided as background information on the use of wooden shelving for aging cheeses and as an analysis of related scientific publications.”

Historically, the FDA has expressed concern about whether wood meets this requirement and these concerns have been noted in its inspectional findings. However, the FDA will engage with the artisanal cheesemaking community, state officials and others to learn more about current practices and discuss the safety of aging certain types of cheeses on wooden shelving, as well as to invite stakeholders to share any data or evidence they have gathered related to safety and the use of wood surfaces. We welcome this open dialogue.

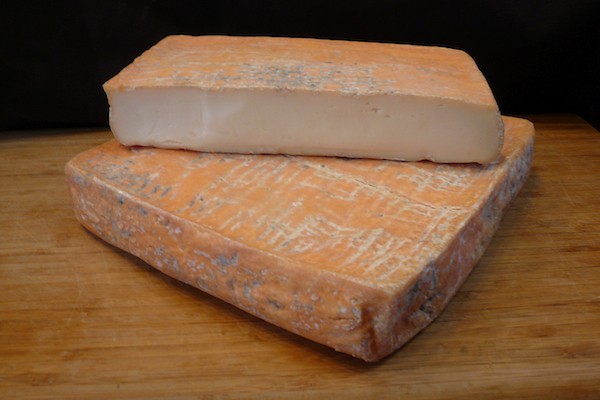

So what does this mean? While they aren’t banning wood surfaces yet, they’re very open about their concerns over the use of a material that they deem unsterile. To be fair, they also claim they’re open to the other side (despite never mentioning who specifically they’ll consult in the artisanal community). Their one-track mind for safety also seems to disregard the characteristics that wood aging adds to cheeses. To put it bluntly, they’re interested in food manufacturing that is perfectly sterile, measurably so, and not in the tangy flavor and creamy texture of Taleggio, which wouldn’t happen without the moisture stabilization caused by wooden shelving.

Wood shelving stabilizes the moisture inside cheeses, changing both the consistency and the sharpness.

Let’s forget about flavor and texture for a moment. Let’s also pretend that every single strain wants to kill you. What’s the solution if you want a perfectly sterile aging surface for your cheese? You need to be diligent about keeping sanitary. Does that mean changing surfaces? The cost of replacing wood aging shelves could hurt cheesemakers and affineurs. Brooklyn Kitchen cheese buyer Aaron Foster says of wood, “It’s certainly less expensive than stainless steel or plastic.” As stated previously by Catherine Donnelly, Listeria is often found on stainless steel surfaces, so that kind of surface wouldn’t be sterile enough. And plastic–we butcher meat on it, don’t we? Yes, but we also don’t consume meat raw until it’s been cooked, the bacteria being killed off by the heat. We can sterilize the surface of plastic, but pathogens like Listeria have a biofilm protectant that shields them from everything except heat. Plastic melts.

So then stainless steel and plastic are out of the question. It’s up to us to keep our wood sanitary–but how do we do that? Wood burns, so you can’t heat it, right? Actually, many cheesemakers already use heating techniques that destroy a bacterium’s biofilm. After a good power washing to remove surface debris, the core temperature of the wood is heated in a pasteurization process, sterilizing not only the surface, but the porous center of the wood as well. Then it’s off to a kiln to dry where the temperature and dry environment add a final bacteria-killing punch that fries the little buggers off the board.

A French cheesemaker powerwashes and air dries his wooden aging boards. / Photo Credit: New England Cheesemaking Supply Company

The rest is just common sense; the American Cheese Society recommends frequent checks to make sure the wood is well-maintained and free of imperfections. If a board is broken, throw it out–they’re cheap enough to replace. There are also treatments that will create a positive biofilm on the board (yes, we’ve come back from that horrible imaginary world where all bacteria want to kills us. There are good bacteria again!), forming an impenetrable barrier against and repelling foreign pathogens like Listeria. Cheesemakers want their products to be safe too, bad cheese is bad for business and they certainly don’t want to harm their valued customers. And if the FDA still wants to ban wooden boards, it should look at how one small change could destroy an entire industry.

Photo Credit: Mitchmaitree via Compfight cc