All sorts of things can go wrong when producers begin overbreeding their livestock. Temple Grandin calls this “biological overload,” and notes that that one must use genomics “carefully so you don’t have problems.” Recently, overbreeding and farmers’ over-enthusiastic use of Expected Progeny Differences—evaluating an animal’s genetic worth as a parent—has resulted in cows with muscle frames too large for their own legs, chickens with brittle osteoporotic bones, and a host of other problems. Grandin cautioned against these practices in an interview with Canada’s Alberta Farmer and in recent presentations at last month’s Society for Range Management meeting in California.

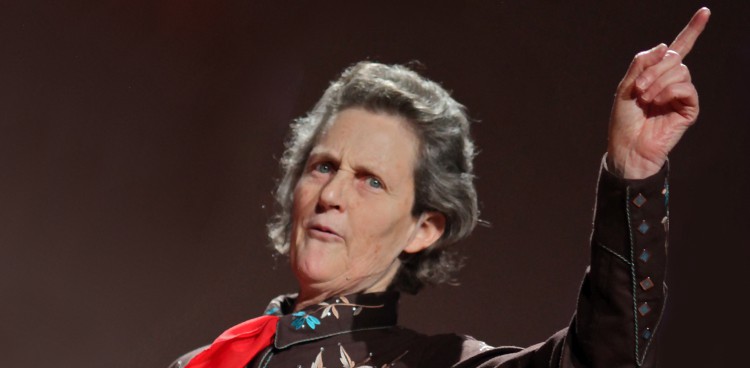

Grandin, an author, autism activist, and professor of animal science at Colorado State University, understands the importance of proper (and smart) breeding techniques. She has long studied animal behavior and is an outspoken expert when it comes to animal-raising best practices. While she lauds feedlots and slaughterhouses for improving much of their handling and slaughtering practices, she still warns farmers that going overboard trying to breed the perfect herd can do much more harm than good when it comes to the welfare of the animals.

In addition to the need to breed heftier cows—so hefty that their legs or cardiovascular systems can’t support their bigger, meatier frames—producers’ push for more milk has spelled lameness and reproduction issues for cattle. Similarly, brittle bones in layer hens is a result of calcium depletion due to increased egg production as well as rough handling. Grandin cited a study out of the University of Bristol, stating that a large percentage of old laying hens have broken bones and beaks due to osteoporosis.

Grandin not only has the best interest of the animals at heart, but also of the producers, noting that farmers must be prepared to be in the public’s eye, a role that is not easy. She notes the importance and necessity of transparency when it comes to producers’ farming methods. After all, consumers are becoming increasingly curious about framing practices, demanding to know where their food comes from and, often more importantly, how it was raised. “We have to look at optimal production,” Grandin urged at a recent International Livestock Forum in Fort Collins, Colorado. Aligning herself with fellow farmers, producers, and agriculture Who’s Whos, Grandin added, “We need to be explaining things to people. Tell our story.” Consumers agree, Professor Grandin.

Feature Photo Credit: “Rain Man’s Rainbow” by Steve Jurvetson, modified | CC BY 2.0