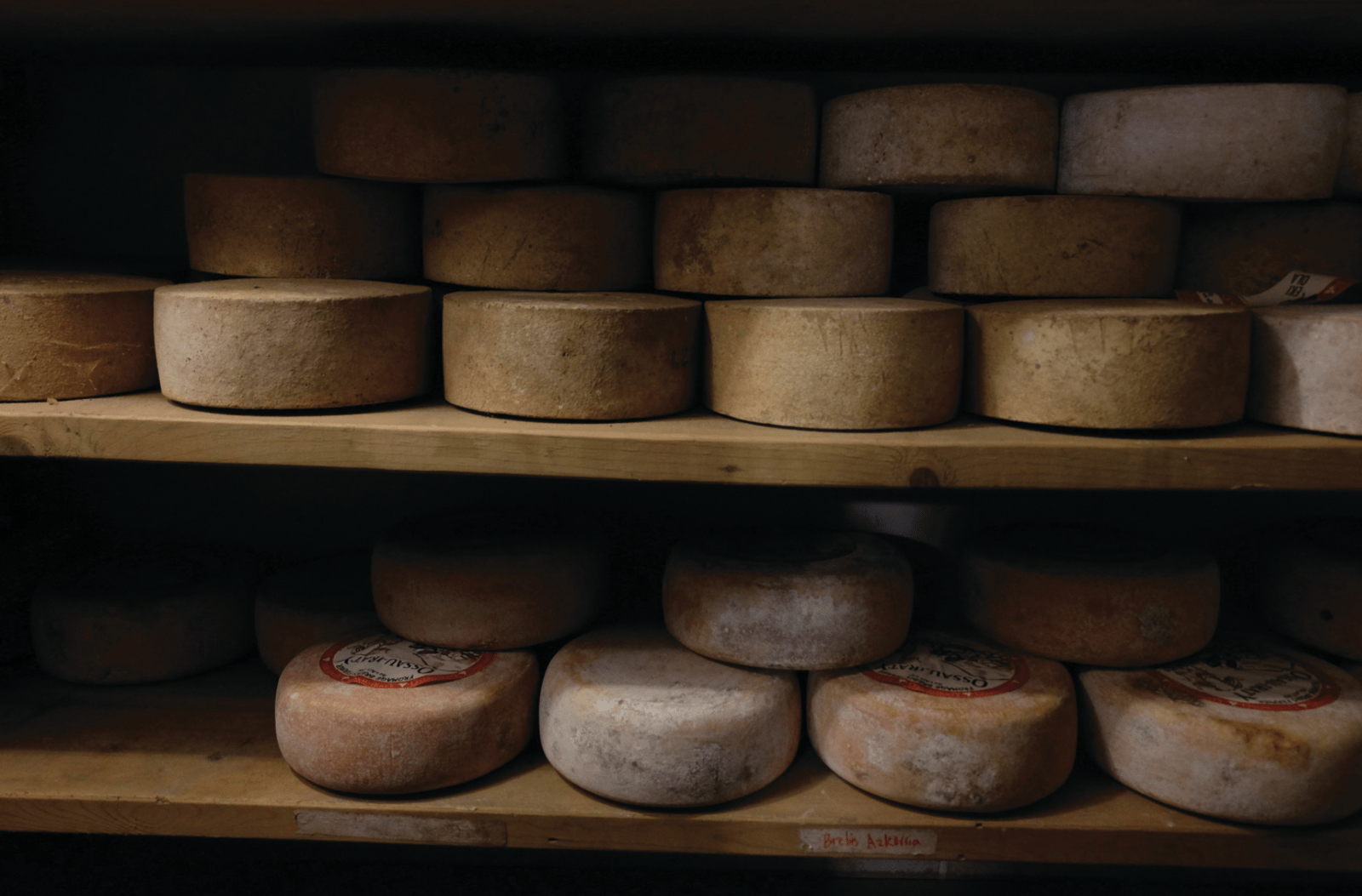

Wheels aging in Formaggio Kitchen’s cheese cave

I work for a museum and run a visual arts magazine. Each week, I attend several exhibition openings, talks, or workshops, and if there’s one thingI can count on, it’s that a mediocre cheese board and a too-sweet bottle of Pinot Grigio will be present. When I’m on the hunt for something better than the flavorless brie I snack on in gallery lobbies, I head to my favorite cheese shop: Formaggio Kitchen in Cambridge.

After several visits to Formaggio, I realized that a good cheese shop is like a good museum; It inspires, educates, and excites the senses thanks to the experts behind the scenes. Like viewing a sculpture on a pedestal, unwrapping a cheese at your dining table is the final stage in a long (and often underappreciated) process.

I’d heard rumors of a cave tucked behind the sprawling counter at Formaggio’s Huron Avenue location, where owner Ihsan Gurdal sought to store imported cheeses in a more traditional, stable setting than a refrigerator. I was fortunate to peek my head into the cave on a sunny spring day when Julia Hallman, Formaggio’s general manager, escorted me down the shallow staircase amidst the hustle and bustle of the kitchen’s lunch rush. Something about descending into the cave was like peering into hallowed archives at the Met while on a guided tour, minus the hand-held audio guide.

“We don’t consider ourselves affineurs,” says Hallman, who throughout her thirteen-year tenure has done just about every job inside the shop. “Rather, we want to pay the cheese and cheesemakers respect by giving each cheese the best long-term storage possible.”

“It’s like art!” I exclaim as Hallman laughs in agreement.

When a work of art enters into a collection at a museum, its first stop is the registrar and conservator where it will be examined—and if necessary cleaned, repaired, and recorded in a database. These crucial first steps ensure that the artwork has arrived in the condition it was promised, which means checking for any scratches, fading, broken parts, or water damage. But sometimes, a long journey in a crate or years of improper storage can leave an artwork in poor shape, creating a hard task for the conservation and curatorial team.

When Gurdal started importing cheeses to the United States, he found himself in the tough position that art conservators sometimes face. Many of the imported cheeses had been damaged during travel, poorly stored, or were otherwise compromised. Gurdal came to understand the importance of cheese storage and care during his many trips to Italy and France, so building a cheese cave, though novel for the US in the ‘90s, seemed like an obvious solution.

The first iteration of Formaggio’s cave was MacGyvered-yet-effective. In 1996, Gurdal transformed his office—situated in the damp basement below the Huron Avenue storefront at the time—by installing several wooden racks, a specialized air conditioner, and a small fountain pumping out a steady stream of water.

Twenty-five years later, the original cave has been dubbed “Old Cave” and holds what Hallman refers to as the more “delicate” cheeses—the ones that require more moisture, like washed rinds and blues. The prized possession? A sheep’s milk brebis from France’s Pyrenees Mountains with a yellow and gray spotted exterior. “This cheese really exemplifie swhy the cave is so important to us,” Hallman says while carefully examining several wheels. She explains that this Ardi Gasna (a Basque sheep’s milk cheese) is made by a cheesemaker with a multi-generational history and finished by a renowned affineur, Christian Pardou, who is known for working with small, local cheesemakers in the region. “The cave allows us to store the cheese with confidence that we are honoring its legacy and giving customers the best possible version of that cheese,” Hallman says.

Back upstairs, the handwritten cheese labels and tiny jars of jam on the shelves make me feel as though I’m no longer on my weekly shopping trip, but transported back in time. This, I realize, is possible because the staff at Formaggio are more than just gourmet food lovers—they’re curators, conservators, historians, and educators actively preserving works of art.

Formaggio is a testament to storing your art well, and your cheese better.