Behind the rise of making cheese at home and the people who shaped a movement

Less than four years passed between the time Mat Lloyd received a £5 cheesemaking kit for Christmas from his sister-in-law and the day one of his cheeses earned international acclaim. At the 2023 International Cheese and Dairy Awards in Stafford, England, Lloyd’s pepper-crusted garlic cheese, Pepper Devil, earned a gold medal in the flavored semi-soft cheese category, and he was named that year’s top novice cheesemaker.

Lloyd remembers his first DIY cheese: a paneer. “It was a simple, tasty cheese,” he says. “From there, I experimented with different recipes, different techniques.” It’s the alchemy that keeps him going. The fact that a spectrum of cheeses can be made from the same type of milk fascinates him. Lloyd’s not yet given up his day job as a business consultant, but he has built a commercial-grade micro-dairy called The Rennet Works Cheese Studio near his home in Gobowen, a village of Shropshire, and says his cheeses sell out within days of being made.

Lloyd is one of 53,500 worldwide members of a Facebook group called Learn to Make Cheese. The group is private, so members are vetted to ensure they are actually humans and not bots or advertising operations. Founded in 2014 by Chera Gunter Renouf, the former owner of cheesemaking gear and culture supplier Cheeseneeds.com, the group shares information about everything from the best recipe for cow’s milk feta to where to source drawstring bags for making clothbound cheddar. Members post about how to construct an inexpensive cheese press and spend a lot of bandwidth determining whether the holes in a pictured homemade cheese are mechanical (good) or a sign the cheese has blown (bad).

Perusing the posts (which hit at a rate of 10 per day), it’s very clear that an ever-present theme is safety. The forum is heavily moderated for all anti-social behavior like bullying or talking politics. And the moderators consistently weigh in on food safety concerns as basic as sanitation, as biological as reminding folks not to make bread or process fruit in the kitchen at the same time as making cheese because various yeasts would be in the air, and as practical as recommending vacuum-packing to lock out contamination or fix a cracked rind during affinage. And moderators and members alike are never afraid to say, “Don’t eat that!” If you’ve spent good money on milk, hours in the kitchen making the cheese, and months waiting for it to age properly, being told by your peers that they see signs of bacterial or yeast contamination in your finished product is never welcome news. But there are always offers from the moderators to do some forensic investigation into your process to see where the contamination might have happened.

Learn to Make Cheese member Annette Lyon has been making cheese in her Connecticut kitchen for about six years. Her first was a mozzarella made during a pandemic Zoom session with her daughter who was living in Los Angeles. Her daughter’s cheese was a fail, but Lyon’s success served as a launching pad into her new hobby. Friends and family members are always up for tasting her cheeses, but not many are curious enough to make them with her, so she enjoys the technical help and camaraderie of the online community. Lyon considers herself an intermediate hard cheesemaker now, having produced farmhouse cheddar, Colby, pepper jack, Cotswold, and Wensleydale cheeses.

There are myriad reasons why members join the group, explains long-time moderator Tracey Johnson. She grew up in southern England but moved to Prince George, British Columbia, in 2012. When Johnson arrived, she was shocked she could not buy Welsh Caerphilly, a staple of her past. “Your cheese choices in this town were orange, white, and orange and white,” she says.

Since the nearest fine cheese shop was located 500 miles away in Vancouver, she poked around the internet for information on how to make cheese at home. She found the Facebook group and jumped in with both feet. Her first cheese was a cheddar, which she readily admits was a hot mess, far too shallow for the mold she used. “It looked like a frisbee,” she says.

Johnson’s participation in the group quickly accelerated. Renouf became a mentor. Johnson pursued formal cheesemaking credentials, purchased Cheeseneeds.com in 2022, and has since taught thousands of cheese lovers to make their own at home. When Learn to Make Cheese members express doubts about ever being able to make some of the beautiful cheeses they see in posts, Johnson shows them the photo of her frisbee cheddar.

DIY Kits

Home cheesemaking, like sourdough bread baking, enjoyed a pandemic popularity surge when house-bound humans had a lot of time on their hands and the national cheese supply chain was experiencing many disruptions, explains Paula Butler, owner of Standing Stone Farms Cheesemaking, a Murfreesboro, Tennessee-based outfit that hosts cheesemaking workshops and sells DIY kits. It’s a slower, deliberate, contemplative hobby that keeps the maker in the moment and, if all goes according to plan, yields delicious results.

Butler was bit by the cheesemaking bug on a 1993 trip to The Inn at Little Washington in Virginia. It was there that she first tasted the fresh, flavored chèvres made by Heidi Eastham of Rucker Farm Tack House Creamery in nearby Flint Hill. Butler went for a farm visit.

“It was magical,” Butler says. “Heidi was wearing a long, flowy skirt and had a handkerchief holding her hair back. She had baby Nubian goats milling around her. Her cheese was hanging in the creamery, so she had time to hang with us.” After a couple of glasses of wine and four or five hours of chatting about cheesemaking, Butler began to think, “I want this kind of life.”

In 2005, Butler moved with her family from the Washington, D.C., area to a piece of land in Gallatin, Tennessee, about 35 miles northeast of Nashville, built a hobby farm, bred a herd of goats—from Maggie and Molly and a buck named Tamatrix—and started making cheese. To offset the cost of her expanding herd, she taught others how to make cheese. And those students needed cheesemaking gear, so she worked with a supplier to assemble kits. Sales for her DIY kits took off in 2011. She sold the farm in 2021 and moved her business to its current location.

A quick Amazon search demonstrates that DIY kits remain a big part of her home cheesemaking story 15 years later. There are over 30 varieties from Butler’s company and a slew of competitors, like Cultures for Health, Fermentaholics, New England Cheesemaking Supply Company, and Urban Cheesecraft. The kits range in price from $10 to $150. At the lower end, you get the basics: a thermometer, citric acid, rennet (liquid or tablets), cheese salt, cheesecloth, safe-handling instructions, and recipes. This essentially equips new cheesemakers to pull off fresh cheeses like ricotta, queso fresco, and paneer. At the higher end, you get the whole shebang: large stainless-steel pots, cheese ladles, fine-mesh strainers, mesophilic cultures, calcium chloride, and cheese molds. Everything but milk, really. With more advanced kits, home cheesemakers are equipped to make aged cheeses like cheddar, feta, gouda, and Monterey Jack.

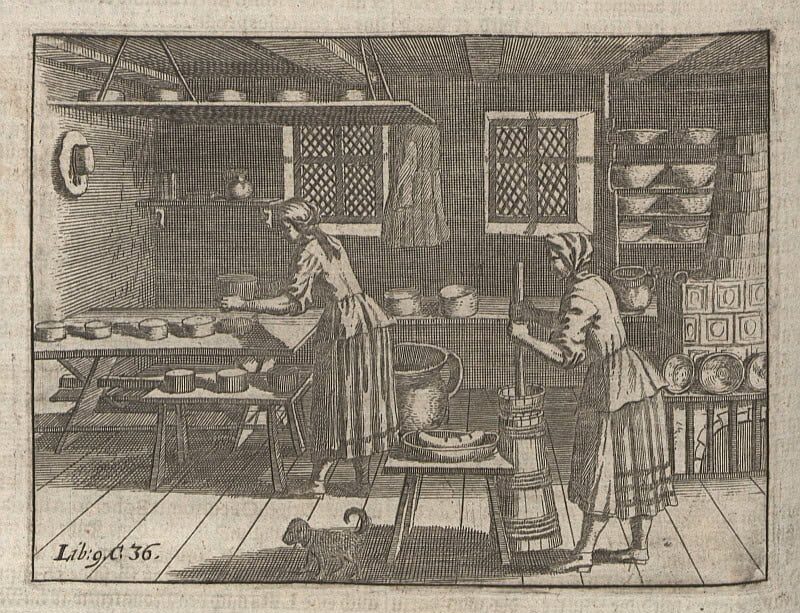

Historically, though, turnkey home cheesemaking kits delivered to your door is not the norm. “Two hundred years ago, all American cheese was made in the home,” writes Ricki Carroll in Home Cheese Making, originally published in 1982 and now in its fourth edition. In 1800, when 90 percent of Americans lived on farms, making cheese was just part of a farmer’s wife’s life. The first US cheese factory wasn’t built until 1851 in upstate New York. The convenience of being able to easily purchase packaged cheese and subsequent federal and state food safety campaigns waged over the next 100 years convinced the general cheese-consuming public that store-bought was always the safer option.

Concerned with the effects industrial food production was having on human health and the environment, the Do-It-Yourself culture of the 1970s reclaimed some of the self-sufficiency skills practiced by their ancestors. Carroll was a vocal member of that group, kept a herd of goats at her Ashfield, Massachusetts, home, and made cheese from their milk. In 1979, using Carroll’s previous book, Cheesemaking Made Easy, Maine-based cheesemaker Caitlin Hunter started making chèvre with milk from her goats using basic kitchen equipment she already had on hand. “My first big investment was a thermometer,” says Hunter, who established Appleton Creamery and went on to make cheese professionally for 40 years. “In those days, direct-set cultures for home cheesemakers weren’t available, so you had to make your own from a mother, much like sourdough.”

That back-to-the-land sentiment is echoed today by the modern homesteader’s movement. In fact, there is a Homestead Cheesemakers Facebook group with 46,100 members. The conversations there are very similar to the larger Learn to Make Cheese group and many members post on both.

The Importance of a Good Recipe

“There are so many cheese recipes out there that you really never have to make the same one twice,” Lyon says. But not all cheese recipes are created equal, Johnson argues. They can have bad or missing information because the writer assumes a certain level of cheesemaking experience. Or they may not account for certain situations, such as if a home cheesemaker has well water and the recipe doesn’t remind them to boil it before washing curds. “Instant contamination,” Johnson says.

Her signature cheese recipe is called Yesterdaze, which she developed in honor of her mother’s 75th birthday. Johnson wanted to mark the special day with homemade cheese, but flying commercially with a wheel posed several logistical and legal challenges. She needed a recipe she could make quickly once she hit the ground in England. Yesterdaze is a brined, fresh cow’s milk cheese that’s ready to eat tomorrow, but it looks like it’s aged, she explains. Her mum was impressed with its mild, gouda-esque taste. Johnson has since published the recipe in Cheese Please!: A guide to the therapy of cheesemaking at home and reviews of the recipe and the cheese are glowing.

Carroll’s book is also widely considered a good source for recipes, as is Cheesemaking.com, the site maintained by New England Cheesemaking Supply Company, which was founded by Carroll and is now run by her daughter. Other books recommended by cheesemakers interviewed for this article include Mastering Artisan Cheesemaking by Gianaclis Caldwell, Artisan Cheese Making at Home by Mary Karlin, 101 Recipes for Making Cheese by Cynthia Martin, and Keep Calm and Make Cheese by Gavin Webber.

“There is no better advice for a home cheesemaker than to start with a solid recipe and follow it step by step. At least the first time so that you understand the processes and know how the end result is supposed to taste, smell, and feel,” Lloyd says. From there, he insists, the sky is the limit for how you can make those cheeses your own.

A Progressive DIY Cheese Repertoire

Mozzarella is simply not a beginner cheese, says Tracey Johnson, owner of British Columbia-based cheesemaking supply company Cheeseneeds.com. “The Internet may have led people to think [it is], and it just isn’t—50 percent of the time you’ll get a wonderful stretch and a beautiful smile for your Instagram pictures; 50 percent of the time you get ricotta,” she says. Making this cheese requires a proficiency in pH measurement.

Instead, start with an acid-coagulated cheese like paneer or ricotta, says Johnson. You’ll need a pot, milk, lemon juice or vinegar, cheesecloth, and a good step-by-step recipe.

“Yes, these lactic-set cheeses are forgiving,” says longtime cheesemaker Caitlin Hunter, formerly of Appleton Creamery in Maine, who is now offering cheesemaking classes. With success under your belt, both Hunter and Johnson say home cheesemakers can progress to rennet-set feta, parmesan, and Caerphilly-style cheeses. Those cheeses will introduce new makers to the processes of cutting and stirring curds.

Then makers can move into more technical cheeses, like cheddars. And finally, Johnson says, cheesemakers will be ready to tackle cheeses like gouda, edam, and havarti that require makers to wash the curds, a process that removes some of the liquid whey and replaces it with warm water.