Another turn in the great cycle of life. Spring started back in December, when it was so warm. The forecasters tell us we’re in for a cold blast, so all the primroses, roses, fuchsias, grass, and even camellias that strutted their stuff in December will get a rude shock. My challenge is to keep the flowers, herbs, and salad going for the Kitchen café if it gets really raw. I love seeing them on people’s plates, challenging them to eat their delicious beauty.

WILDLIFE – A hard frost is tough for the wildlife too. Deer can nuzzle away snow to get to the grass (and crops) to feed. Animals that dig for worms, slugs, and assorted yummies hidden under long-term pasture start finding that a challenge, particularly if weakened by disease. So we’ve revved up our protection of our animals to stop any sorrowful badgers getting close to our cattle. Foraging birds look for our untrimmed hedges, and a bold robin follows me around as I turn soil over in my garden.

CROPS – The crops can shrivel with cold drying winds; a blanket of snow keeps them safer. The roots will be safe either way; mostly the frost acts as a fungal treatment, shriveling any diseased leaves. We ‘store’ the grass that grew in the warm time pre-Christmas on the pasture to feed the cows when they calve in early February. Farmers often worry about ‘winter kill.’ My experience is that if you leave lank, undergrazed grass, that can be damaged by a cold snap. If it’s short or healthy enough, even quite long grass survives frost—look at your lawn or grass verges.

COWS – Our milking animals are all inside on silage. They stand by the gate, sniffing the grass growing on warmer days. Patience! As soon as the ground is strong enough you will be out, end of this month or early next, we hope. They are all in calf and now getting on with the pleasurable business of milking, that intimate and generous time when as a milker you provide them the relief they need and they give their bounty to you. No wonder the Hindus worship them.

HEIFERS – The dry cows and heifers are half in buildings, half out on crop. They did so well last year outside, despite atrocious weather. We wanted to see if we can take the steps to keep any unwell wildlife away from them on the crop (triple electric fencing and no hard feed outside). We wanted to hedge our bets, so half are inside. That presents its own challenges; unwell wildlife is drawn to buildings where feed is if the ground is hard, so we’ve done what we can to proof the buildings. Even in very hard weather, cattle still seem to prefer outside, going into a sort of hibernation as they stand together, the herd providing shelter for the individuals.

CHEESE – In the cheese dairy, we make much less cheese in January as many of the animals are dry. The January milk is surprisingly rich, even with preserved and not fresh grass. Our breed mix of New Zealand Friesian, Swedish Red, and Montbeliarde maintain a rich, flavorsome milk through the year.

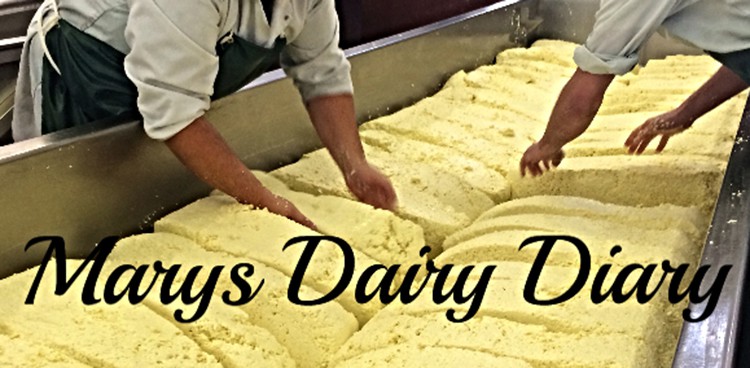

I was asked to say how we make the different cheeses. Almost all cheeses are made with quite subtle changes to the basic recipe of milk, cultures, rennet, and salt: remarkable when you think of the huge variety of cheesy wonderfulness that arises. All our cheeses come from small differences in the amount of culture, the temperature of the scald (cooking of the junket)—just 6 degrees of Fahrenheit or 3 degrees of Centigrade separate our cheddar from our Double Gloucester, which is enough to develop a softer, sharper-flavored cheese. We add annatto, the dye from the seed of a South American tree (you can see it in the Eden Project) to make the Red Leicester and the Double Gloucester red. We handle the curd in the same way, draining the whey and cheddaring (turning the blocks of curd several times). The lower temperature of the Double Gloucester and Red Leicester scald means they get slightly more (0.01 to 0.05%) acidity developing in a shorter time. That means they hold more moisture, and we need to take care in salting or too much salt gets washed out, which can lead to bitterness. We’ve worked out how to hold the salt in, so now these cheeses are sharp and buttery in flavor.

Recipe: Whey Butter and Pancetta Brioche

I’ve used this lovely recipe from Slow Food’s forgotten Foods recipe bank, highlighting our hand-rolled whey butter. You can find it here. Chef Joe Mercer Nairne baked these loaves for his kitchen brigade’s breakfast and they went down a storm! Breakfast, brunch, lunch, or dinner, these tasty Brioche offerings would be a delightful treat any time of the day!

Ingredients (for 8 loafs)

- 250g unsalted whey butter

- 420g T55 flour

- 22g fresh yeast

- 42g sugar

- 17g salt

- 5 whole eggs

- 8 slices of pancetta

Method

- In a kitchen aid bowl measure out yeast, flour, sugar, and salt. Refrigerate for at least 2 hours.

- Dice the cold whey butter.

- Attach the kitchen aid bowl, pour in the eggs, and start the mixer. Once combined start feeding in the cold diced butter.

- Once all the butter is incorporated, keep mixing at high speed until you have a strong elastic dough. Refrigerate for at least 6 hours.

- Line 8 individual brioche molds. Cut the dough into 16 equal pieces. Place one piece of dough in the bottom of each mould then lay a slice of pancetta on top. Place a second piece of dough over the pancetta. Allow to proof for one hour or until the dough is bulging over the top of the mold.

- Preheat the oven to 175°C.

- Glaze with egg yolk and place in the oven for 12 minutes until golden brown.

- Turn out onto a wire rack and cool.

Yum!

Something to do on a cold January day!