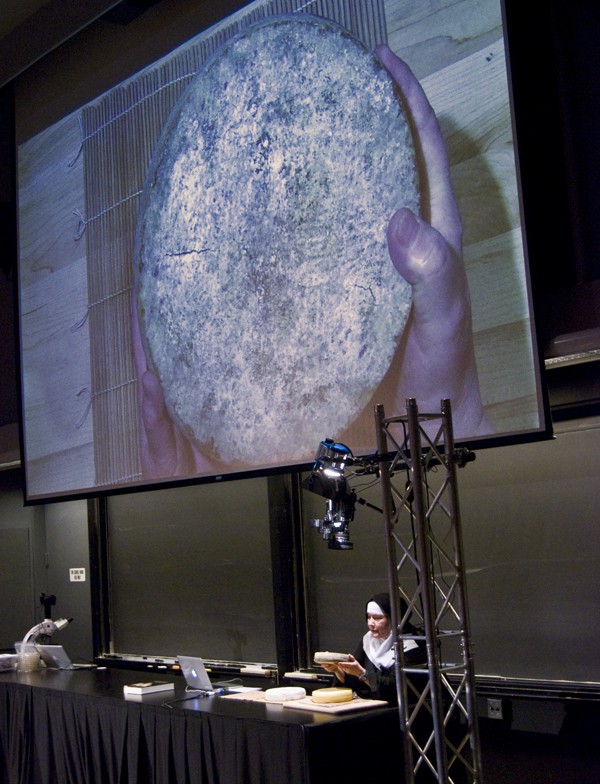

Last night, Harvard Science Center was packed with cheese nerds eager to learn about the intersection of cheese and microbiology from both Sister Noella Marcellino, Ph.D. of Abbey of Regina Laudis (lovingly referred to as the “Cheese Nun”) and Mateo Kehler of Jasper Hill Farm—plus bonus guest Ben Wolfe, Ph.D., a microbiologist at Tufts University. The talk, “Delicious Decomposition: Tales from the Cheese Caves of France,” was the latest topic in the school’s annual Science and Cooking Public Lecture Series.

Ahead, enjoy a few of the educational highlights you missed:

The human love affair with cheese dates back to 6,000 BC

Rock carvings found in the Wadi Teshuinat cave in southwest Libya show scenes of daily prehistoric life, including milking cows and making dairy products. There’s even a depiction of a calf standing near its mother while she’s being milked—a common practice for some breeds that need to see their offspring to let down milk.

You can age cheese solely using the air we breathe

Sister Marcellino ripens her cheese using the natural flora of Bethlehem, Conn. The process begins the day the cheese is formed, when natural yeast starts to consume the lactose in the milk. By the time the cheese is ready for market, it is home to a complex and delicious ecosysytem. “What happens in the cave is a transformation,” Sister Marcellino said, “One gram of soil contains 10 billion microorganisms and perhaps thousand of different species. So what we do is we put cheese in a cave so it can be close to the soil.” Unlike many cheesemakers, Sister Marcellino doesn’t add any commercial cultures to her cheese.

It takes a multi-generational microbial village to make a cheese

Each successive microbe in the aging process of a given cheese is able to move in because of the environment their predecessors created for them. As Sister Marcellino described it: “Something like geotrichum . . . burrows down into the cheese surface and almost tills the surface, aerates it so other microorganisms can go down into those channels.”

Biodiversity in microbes equals diversity in cheese flavors

“The diversity of the local strains of microorganisms in the region contributed to the diversity of the cheeses in France,” explained Sister Marcellino. “Just as you want to save a certain kind of tree in the rainforest, you want to save the microbes that are part of a region because they’re the ones that contribute to the flavor and special unique character of the cheese.”

Mateo Kehler from Jasper Hill Farm and Dr. Ben Wolfe from Tufts University talk microbes and cheese.

It’s hard to recreate terroir after pasteurization

“The microbial ecology of raw milk is the sum of the practices on the farm,” Kehler explained. All microbes that contribute to cheesemaking come from the unique environment outside of the udder. When asked about what pasteurization does to milk, Kehler responded: “What does it do? It wipes everything out. You start with a blank slate and then you have to try to recreate, artificially, this diversity.”

This myriad of colors exemplifies the diversity in microbes that make the cheeses we eat every day. Photo credit: Wolfe et al, Cell, 2014

If you’re a science geek and a caseophile, you want to be Ben Wolfe when you grow up

“What we are trying to do in the lab is not to just understand a single cheese . . . but all cheeses in the world. What microbes are out there and what patterns of diversity of those microbes. It’s food CSI,” said Wolfe. Cheesemakers don’t always know exactly what microbes are creating their cheeses. Wolfe’s work strives to idetify these microbes so that makers can recreate a cheese traditionally made in another part of the world and also identify nasty invaders and determine why the intruders moved in.

No matter the cheese event, someone asks “When should I eat the rind?”

Sister Marcellino immediately answered, “Did you already eat it?” Kehler then chimed in: “It’s where all the work is! These rinds are soaked in labor!” They both continued to explain that no matter what—beyond wax and cloth bandages, of course—eating the rind won’t hurt you. It’s a matter of personal preference.

All photos by Ryan Kaminski-Killiany