It’s no surprise that paradise has long been imagined as a land flowing with milk and honey. Dairy and nectar might just be nature’s most exquisite gifts: forage and flowers transformed, within the bodies of living things, into substances that nourish while embodying botanical complexity.

Admittedly, here at culture, our idea of utopia trends toward a land of milk. But since we’re pairing fanatics, there’s definitely at least one honey river flowing in our imagined paradise. Besides, what would milk be without bees, the pollinators that sustain the plants that feed livestock? Across ecosystems, milk and honey are inextricably linked; on our plates, the combination is its own little nirvana—rich, plentiful, and simply divine.

So let’s delve into the sweet stuff in all its renditions, from booze to medicine, hive sustenance to cheese plate pairing star. Trust us: The land of honey definitely merits a detour.

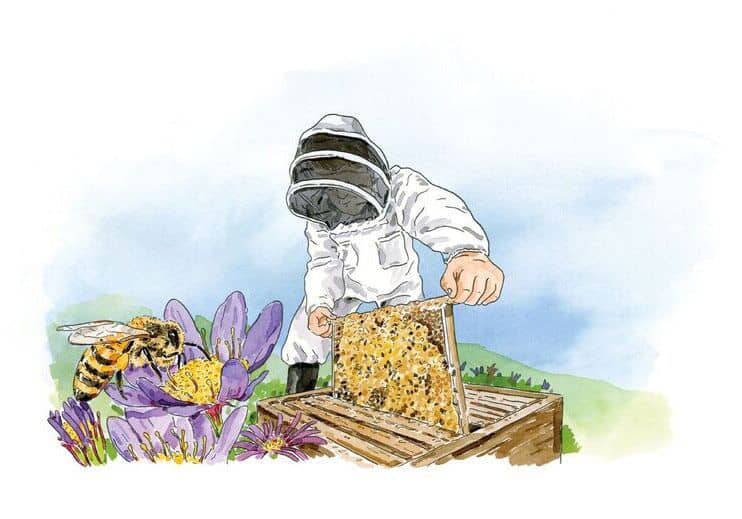

To understand this melliferous miracle, peek into the hive.

1. Flowers and bees have evolved side by side, forming a symbiotic relationship. The blossom produces sweet nectar to attract the bee, which in turn transfers its pollen to other flowers, germinating the next generation.

2. An adult worker bee reaches its straw-shaped tongue into the flower to draw out nectar, which it stores in its body in a special “honey sac.” There, digestive enzymes start breaking down the nectar’s starch into glucose and fructose.

3. The adult worker bee returns to the hive, which harbors a colony with a complex social structure. Here, young worker bees secrete wax to build and maintain the honeycomb, a single queen bee lays eggs, and drone bees mate with the queen.

4. Worker bees deposit the now-concentrated nectar in a thin film on the honeycomb. Once the combs are full, bees seal them shut with a wax layer. Here the honey continues to ripen, with enzymatic changes resulting in the development of flavor and aroma.

5. The beekeeper removes a frame from the hive, then removes the wax layers used to seal the honeycombs shut. At this point, the honey can be consumed or stored. Some beekeepers use a centrifuge to encourage honey removal from the frames, a strainer to remove bits of wax, or heat to extend shelf life.

Milk & Honey

Kasey Francia, ACS CCP and assistant manager at the Bleecker Street outpost of Murray’s Cheese in New York City, composes a platter showcasing her favorite honey pairings.

Caseificio Quattro Portoni Quadrello di Bufala + Honeygirl Meadery Blueberry Mead

“The high butterfat of the water buffalo’s milk perfectly balances a sweet drink like mead, allowing the tartness of the blueberries to shine through.”

Murray’s Cavemaster Reserve / Käserei Tufertschwil Annelies + Mitica Oak Honey

“This combo applies one of our main pairing principles—to marry like flavors with one another. Both the cheese and the honey have rich notes of woods and nuts; together, they taste like a peanut butter and honey sandwich.”

Jasper Hill Farm Bayley Hazen Blue + White Gold Honey

“Blue cheese and honey is a great combo for those who are wary of blue cheeses; the honey has just enough sweetness to mellow the spicy notes of the Bayley Hazen.”

Vermont Creamery Coupole + Red Bee Farmhouse Honeycomb

“Not only do these two look visually stunning side by side, but the delicate sweetness of the honeycomb subdues the tang and acidity of the soft goat’s milk cheese. The textural contrast between crunchy honeycomb and smooth, silky cheese also creates the perfect bite.”

Roncal PDO + Mike’s Hot Honey

“This honey causes heat on the palate, but it’s soothed by the buttery sheep’s milk cheese, which in turn yields a subtle sweetness that marries with the honey.”

Ask a Beekeeper

What is monofloral honey and how do you make it?

Andrea Paternoster is a third-generation nomadic beekeeper in Italy. He owns Mieli Thun, a monofloral honey company started by his grandfather in 1921.

Monofloral honey is harvested from bees that live near the blossoms of a particular flower, therefore obtaining most of their nectar from that flower. At Mieli Thun, we move our bees in search of specific blooming flowers—a bit like a shepherd who moves his herd in search of greener pastures. It’s a beautiful job with plenty of contact with nature.

For example, we make our coriander honey during the first week of June. During one night, when all the bees have returned home, we move them to an area near coriander farms where the plants are just beginning to bloom. We open the doors of the hive in the early morning before sunrise, and after a few hours the bees are in flight searching for flowers. They quickly find the white, fragrant blossoms and collect the nectar. In this way, we obtain pure honey from that flower.

The taste of that honey is very different from the leaf or seed of the plant; it’s fruity and fragrant, with notes of toffee, caramel, cooked milk, and tropical fruit. A professional taster should be able to verify the monofloral origin of the honey just from sensory analysis. But its origin can also be confirmed in a laboratory, where the pollen itself can be analyzed.

How to Taste Honey: Pro Tips from Marina Marchese

When we treat honey like a homogeneous condiment, we don’t give it the credit it deserves. “The general public seems to think that all honey tastes the same,” says Marina Marchese, co-author of The Honey Connoisseur (Black Dog & Leventhal, 2013). “But there are thousands of different varietals, each with its own unique flavor profile.”

Marchese should know. Aside from being an experienced beekeeper, she trained as an expert in honey sensory analysis in Italy and founded the American Honey Tasting Society. Marchese calls herself a “honey sommelier,” a concept that doesn’t seem like much of a stretch given the striking variety in the product and its link to the land—a level of complexity akin to wine.

- Prep your tasting. Like wine, honey should be sampled from lightest to darkest. Serve it in a transparent stemmed wine glass. Like cheese, it should be served at room temperature. Water works well as a palate cleanser.

- Examine the color of the honey, as well as its degree of transparency or opaqueness. (To trained tasters, color helps indicate both floral source and mineral content.) Turn your glass slightly to evaluate viscosity and texture.

- To get those aroma molecules moving, smear the honey using a small spoon around the sides of the glass. Dip your nose into the glass and sniff. The aromas you sense relate to the honey’s botanical source; they might be floral, earthy, fruity, resinous, or musky.

- Scoop up a small taste and let it melt on your tongue. Aside from the requisite sweetness, do you detect other tastes, like bitterness or sourness? Evaluate texture in the mouth: Does it feel velvety, creamy, runny, gritty, buttery, or crystallized?

- Let the flavor linger, considering how it progresses. Is it mild or assertive?Long-lasting or abrupt? Evolving or one-dimensional? A quality artisanal honey should have layers of flavor and an identifiable source, and it shouldn’t taste “off”—fermented or burnt flavors tend to indicate defects.

Ask A Beekeeper

Why Does Honey Crystallize?

Rusty Burlew is a beekeeper and writer in Washington state. She blogs about bees at honeybeesuite.com.

Crystallization is a completely natural process that occurs when the molecules of honey arrange themselves into little cubes—much like granulated sugar. Honey is mostly made up of glucose and fructose, the amounts of each varying according to what plant the nectar came from. Since glucose tends to crystallize quickly, and fructose slowly, those proportions make a difference. For example, honey from alfalfa has a high glucose content, so it granulates quickly, whereas honey from tupelo flowers has a high proportion of fructose, so it granulates slowly.

Creamed honey is a popular spread made by deliberate crystallization; Seeding honey with very tiny crystals causes the honey to take on a smooth, spreadable texture. Although many people try to reverse crystallization by warming it, heating honey above internal hive temperature (about 95°F) can degrade both its flavor and nutritional qualities. Learning to enjoy crystallized honey is a better choice—plus, it won’t drip off your toast!

How to Infuse Honey

- Clean and thoroughly dry an 8-ounce jar. Add 1 to 2 tablespoons of desired herbs or spices to jar. (Try: black peppercorns, sage, orange zest, garlic cloves, star anise, or any spice that tickles your fancy. Plus, find more flavors here.)

- Choose a mild, non-crystallized honey. Pour honey into jar with herbs and spices and stir to combine. Cover and let rest at room temperature. Taste honey each day until flavor reaches desired strength.

- Strain honey to remove herbs and spices and discard solids. Return honey to jar. Store in the refrigerator for up to 6 months.

- How to make hot honey: Add 1 cup honey to a small saucepan along with 2 to 4 whole chiles of your choice (try Calabrian, Fresno, or Thai), sliced lengthwise and seeded. Bring mixture to a simmer over medium heat. Simmer for 5 minutes, then reduce heat to low and cook for another 30 minutes. Taste, add additional chiles as necessary, then cool to room temperature. Clean and thoroughly dry an 8-ounce jar. Strain honey mixture into jar, then discard chiles. Keep for up to 1 month, refrigerated.

Our Favorite Honeys

L’Abeille Occitane Miel de Châtaignier

leather, tannins, bitterness, salt

Botanical source: Chestnut trees in France

Pair with: Alpine or grana styles

Mieli Thun Coriandolo

raisin, chocolate, orange peel, coconut, licorice

Botanical Source: Coriander flowers in Italy

Pair with: Washed rinds

tropical fruit, tartness, anise, jasmine

Botanical source: Ulmo trees in Chile

Pair with: Chèvre

smoke, molasses, yeast

Botanical source: Miombo forests in Tanzania

Pair with: Fresh lactic cheeses

grass, wood, menthol, thyme

Botanical source: Linden trees in Bashkortostan, Russia

Pair with: Bloomy rinds

violet, blueberry, lemon, sweetness

Botanical source: Wild blueberry bushes in Maine

Pair with: Blue cheeses

butter, prune, raisin, caramel

Botanical source: Tulip poplar trees in the southeastern United States

Pair with: Basque-style aged sheep’s milk cheeses