Paso Robles—located halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco—is perhaps best known for its robust wine industry; Its proximity to the coast along with ideal growing conditions make it a mecca for tourists and vintners alike. But the city is also home to a number of small farms and dairies. It’s hard to know the average Californian’s perception of a farm, but there’s likely a certain expectation of small-scale producers—that the operations have been handed down through generations and a level of instinctual practice and hereditary knowledge is at play. But talk to any rancher or farmer in the Central Valley and you’ll quickly find that precision is key to strong production and there’s little room for error when it comes to staying afloat.

A Well-Rounded Career

With nearly 30 years of experience in the dairy industry, Reggie Jones, founder and head cheesemaker at Central Coast Creamery, knows his way around a wheel of cheese. While some would assume his passion was cultivated by a life surrounded by dairy, it was actually quite the opposite. “I got into cheese by happenstance,” Jones says. “I had a degree in biological sciences, and no job.” After signing up at a temp agency, he was placed in a lab at a large-scale cheese factory and things just clicked. Jones quickly moved his way up to plant manager, overseeing the production of over 2,000 pounds of cheese a day and a team of over 400 people. Later in his career, Jones worked for a group that specialized in whey refining technology before taking over regional sales for a large seller of cultures and enzyme.

Jones always knew he wanted to open his own creamery. From his point of view, there was a clear gap between small-scale niche producers and the colossal creameries churning out cheese for the masses. “I made a comment to my wife 20 years ago that [there will be] very big cheese factories and very small ones, and nothing in the middle. You can’t be in the middle and make commodity styles and compete with the big guys, and you can’t make artisanal [if] your equipment’s too big, so you can either be small or large.

For his cheeses, he knew which direction to go: “I wanted to be small and make quality products. I thought that more complex flavor profiles were the next logical step for American palates.” But that didn’t mean he couldn’t bring everything he’d learned from large-scale operations with him to this new endeavor. “There’s no doubt that the road I traveled gave me the experience required to make it happen,” he says.

For Jones and his wife, Kellie, co-owner of Central Coast as well asa biochemist and pharmacist, Paso Robles felt like the perfect place to start. “We conceptualized the company in 2007, and while coming up with a name ,thought about where we [wanted] be. Paso Robles was this burgeoning wine area and [while] there were a couple cheesemakers here, they were very small.”

Production space was cheaper than areas with a more established cheese scene, like Point Reyes or Sonoma, and it helped that nearby California Polytechnic State University was Kellie’s undergraduate alma mater.

Playing the Long Game

Most new cheesemakers ease into things, starting off with soft cheeses that age quickly to kick-start sales. Instead, Jones began with Goat Gouda (now a multi-award winner). “We wanted [it] to be four or five months old. So, you’re in business, then you have to wait to see what the final flavor profile and result is,” says Jones. Keeping his day job as regional sales manager, Jones spent Central Coast’s early months refining his process and seeking out dairy producers; it was important to him that the milk was local, single-source, and came from happy animals. This was an easy enough task for their cow’s and goat’s milk cheeses, but sheep’s milk proved to be hard to find. So Jones turned to Europe.

Ewenique, made with 100 percent sheep’s milk, was initially produced for Central Coast in Holland using milk from Spain. From an economic standpoint, it made perfect sense: Sheep’s milk is easy to come by in Europe, and usually at a very reasonable price point. Ever aware of the importance of supporting domestic producers, once Jones was able to secure a constant supplier of sheep’s milk cheese in 2018, they brought production home to Paso Robles. “It became a philosophical problem. We saw how tough it is, not only for our dairy producers here but also for our fellow cheesemakers. You see every year, people going out of business—a lot of that has to do with cheap imported cheese coming from overseas. We didn’t want to be a part of that problem.”

Over the years, the creamery’s line has grown to include numerous award winners, like Goat Cheddar; the Alpine-style Bishop’s Peak; semi-firm, mixed-milk Seascape; and Holey Cow, a creamy, whole-milk Swiss style—the only of its kind produced in California.

Process and Culture

Nearly all of Central Coast Creamery’s cheeses are aged at a lower humidity, keeping them semi-firm with a tight natural rind and a noticeable lack of mold. From the start, one of Jones’ main goals was to create cheeses that would appeal to a variety of palates and could withstand nationwide distribution. This meant foregoing a lot of the aging and packaging experimentation that most small producers are wont to do.

Every step of Central Coast’s process is meticulously planned, from their milk processing schedule—sheep’s milk on Mondays and Fridays, cow’s milk on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, and goat’s milk Wednesdays and Thursdays—to the forming of their wheels, which are rotated and pressed multiple times to ensure the fortitude of their rinds. The thought that goes into the development of each cheese is equally matched by the care Jones puts into the company’s culture.

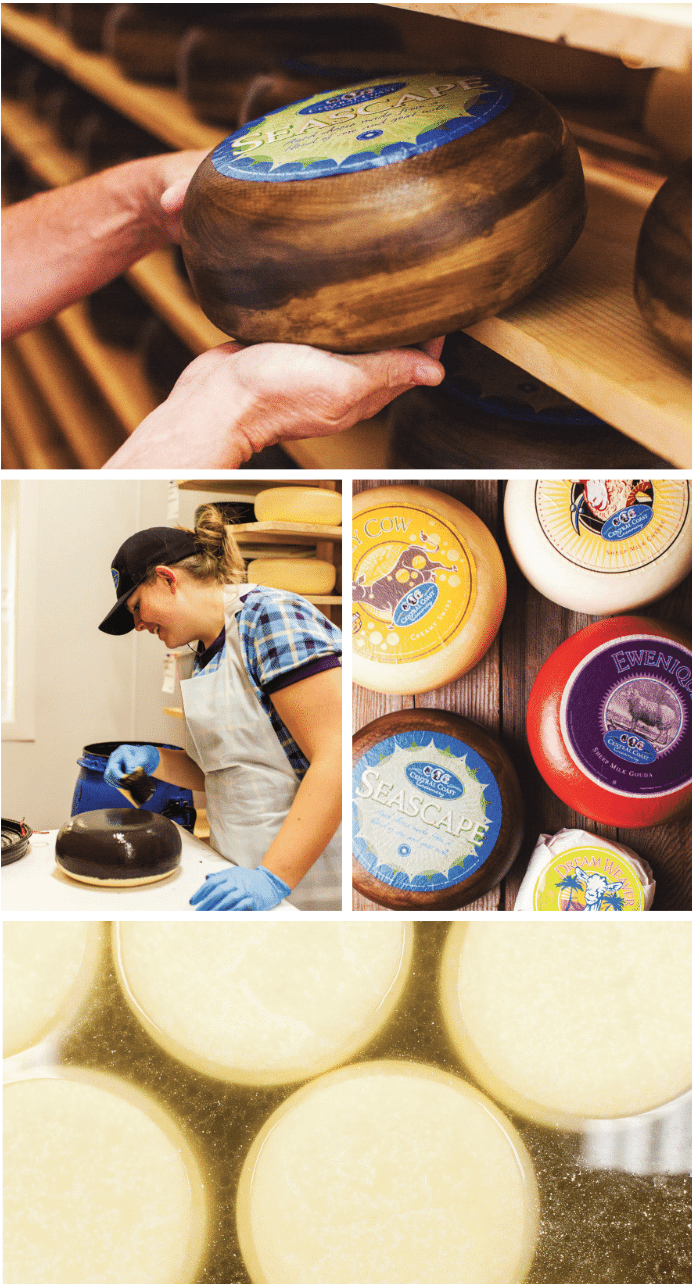

Clockwise from top: Semi-hard Seascape, a mixed cow and goat’s milk cheese; a variety of Central Coast Creamery cheeses; wheels in brine; wax being applied to Goat Gouda

To wit: All of Central Coast’s milk suppliers are family-run farms located within a few hundred miles of the creamery. The whey from each batch of cheese is stored until local pig and cow farmers pick it up and add it to their feed. The creamery is closed on weekends to allow employees time for themselves and their families. Recently, Reggie and Kellie’s teenage daughter, Avery, has followed them into the cheesemaking business, launching Shooting Star Creamery and experimenting with her own line of cheeses. “She’s following [our] road map,” says Jones. “It’s very smart because Central Coast Creamery has all the distribution channels already setup—it should be easier for her to get products approved.” So far, Shooting Star is off to a great start, winning third place Best of Show at the 2019 American Cheese Society Judging and Competition with Aries, an aged Alpine-style sheep’s milk cheese.

Risk and Reward

One would hope that making exquisite cheese was enough to sustain a business, but artisan cheesemaking is often a losing game. It’s hard to know which cheeses will be hits and which will fall flat—even those well-received by judges and distributors can be ignored by consumers. One of Jones’ favorite cheeses, Bishop’s Peak, will soon be retired due to lack of sales. It’s a story many producers know, not just within the cheese industry but across the food world. Yet, this struggle also lends itself to innovation—in Central Coast’s case, the creation of Dream Weaver, the creamery’s first washed-rind goat’s milk cheese, as well as several soft cheeses currently in development. “It’s funny how you can have a concept and then it completely changes,” Jones says. “You have to keep evolving.”

Central Coast Creamery will be doing even more to make itself a household name. Their first retail store is opening soon in Santa Cruz, and another shop will follow shortly after in San Luis Obispo. The Santa Cruz shop will be run by a cheesemaker, with the hope that customers will get in-depth explanations on the creamery’s process as well as accurate descriptions of flavor profiles for all the cheeses. “People are going to come into the store and ask questions and they’re going to be able to get our whole story,” Jones says.

Eventually, Jones hopes to open a second creamery in the southeastern US to bring a special line of cheeses to the East Coast and expand their network of dairy producers. But for the immediate future, the focus remains here in California, where this creamery will continue to churn out quality wheels and build up their presence in the cheese world and beyond.