Yes, Korea has a cheese scene.

Last week I found myself wandering the streets of Hongdae, a popular commercial district packed with people my age (twenty-something-year-olds). Restaurants in this area serve traditional Korean street food with an unexpected twist: cheese. Spicy dishes, like tteokbokki (spciy simmered rice cakes) or dakgalbi (spicy stir-fried chicken), are often paired with mozzarella cheese to cut the heat of gochujang (red pepper paste) or gochugaru (ground red pepper) dishes. If my ancestors were to witness these cheese alterations, they would not know what to make of it.

Korean food was not always paired with cheese. In fact, Koreans traditionally did not consume milk. During the Josun Era, milk was prohibited from consumption. At that time, cows were prioritized for agricultural labor., andcows’ milk was reserved for calves. It is estimated that the first time Korea was introduced to cheese was in the early 1920s, but enjoyment was strictly limited to foreigners and upper class citizens.

The first Korean cheese was made from goat cheese. Belgium missionary Didier Serstevens, who served as the head priest of Imsil church from 1964, raised two goats (specifically, long-tailed gorals) in the open fields of Imsil, which he received as a gift from another priest. Imsil is a remote town in the North Jeolla Province of Korea and, when Serstevens first arrived, the people who lived there relied on agriculture and livestock to make a living. Serstevens, hoping to spur local business, sold goat’s milk and, soon, cheese.

The operation began in a small cave measuring neatly 23 feet. Inside, the first iterations of cheese were made using yeast from makgeolli (Korean fermented rice wine). By 1968, Serstevens and his team at Imsil successfully made Camembert cheese with the help of a French employee who had about one month’s worth of experience. The following year, Serstevens embarked on a three-month long journey to Belgium, France, and Italy to learn cheesemaking techniques. He said his heart fluttered when he was able to return to Korea with notes on manufacturing cheese from an Italian expert. Yet, upon returning to his post in Korea, the priest was greeted by only one remaining worker. The rest had grown skeptical, and sold their goats and left the Imsil Creamery.

Nevertheless, with the turn of the decade, Serstevens began producing cow’s milk cheeses such as cheddar and mozzarella. He sold these cheeses under the geographically eponymous name Imsil to his steadily growing customers, who were mostly foreigners and Seoul’s top hotel restaurants. Throughout the seventies, other Korean creameries cropped up, both artisanal and processed. In 1987, HaiTai Foods Company introduced sliced cheese to the Korean market, and several other creameries began producing processed cheese, notably pizza cheese. Also introduced in the late 80s were processed cheeses specifically marketed towards children and young adults—Seoul Wooyoo produced sliced cheese that claimed to have no artificial coloring or preservatives, and Namyang Dairy Company branded their DHA-enhanced sliced cheeses as “Children’s IQ cheese.”

Today, Korea produces several cheeses for mass consumption. They include a mix of fresh and aged cheese styles, like mozzarella, ricotta, cheddar, emmental, camembert, brie and gouda. A demand for halloumi, string cheese, and various snackable cheeses has contributed to a significant growth in cheese production. Among imported cheeses, Parmesan, Feta, and Provolone have proved to be the most popular. Korean cheeses are characterized by their milder taste compared to western counterparts, and all artisanal cheeses produced in Korea receive “K-cheese” certification.

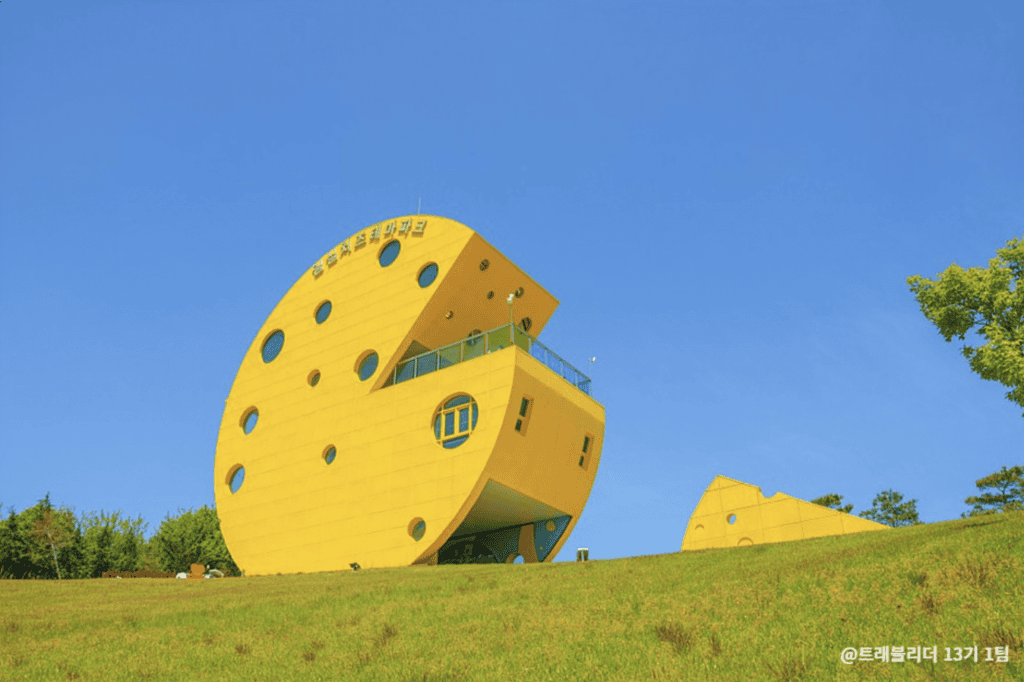

While Imsil itself remains a small agricultural town, Imsil Creamery has established a Cheese Theme Park and Cheese Sciences Laboratory. The latter serves as a research facility for Imsil Creamery. The former holds workshops, including hands-on mozzarella-making classes, in addition to an exhibition space, gift shop, restaurant, and outdoor installations. The Theme Park was designed to replicate the village of Appenzell in Switzerland. Deputy Director Han Jung-seog attributes the success of Imsil Creamery to local dairy farmers. There are 12 ranchers in the town of Imsil and “they wake up as early as 5 a.m. every morning to milk and produce fresh cheese, in addition to milk and yogurt.”

In an era of burgeoning growth in Korean culture, a challenge remains for the Korean cheese industry. Only three percent of artisanal cheeses in Korea are produced domestically. The Imsil Cheese & Food Research Institute recommends that Korean creameries produce more fresh cheese styles, like mozzarella or halloumi, leveraging recent efforts made by the industry to promote local dairy products. Further, producing fresh cheeses remains a financially and gastronomically competitive strategy, especially against the imported aged cheeses that dominate the global, let alone Korean, market.

To revisit my original question, I’m not quite sure what my ancestors would make of melted cheese on their food. Strange, they would think surely, but like or dislike? Who knows. What is for sure is that they would give credit to the cheese producers and public—their descendants—who have turned something so foreign into their own.