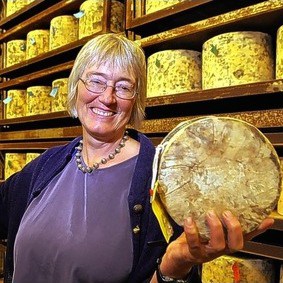

Find out what’s happening this month on Mary Quicke’s farm in Devon, England, where she and the team make the award-winning Quicke’s Traditional Clothbound Cheddar!

When I was a child, it felt like we always had two good weeks of frost in February. That desiccates diseased leaves, so plants are healthier. The soil structure gets shattered with the frost, giving lovely friable tilth. The slugs and slug eggs and bugs and bug eggs freeze, and the weakest wild creatures starve, giving a clean start to the spring.

Recently, we’ve had a warm run of Februaries—slugs, bugs, the weakest young, and molds all survive, giving more mouths for our crops to feed. So we are looking forward to some promised cold weather. No doubt we’ll complain when it’s here.

The warm mid-winter kept everything growing. The pastures kept the luminous green of active growth. My damson tree flowered. The bumble bees kept buzzing. It feels like all that growth is over—hopeful, skipping unwarily into the jaws of the frost that must surely come, a ravening wolf from the Arctic behind the wandering jet stream. And the later the frost, the shorter the cold time, as the lengthening days coax warmth back into the soil and water.

CROPS – The new life promised in the warm winter may get singed by cold, and it will recover. The wheat and barley are hardy troopers, frost resistant until they flower. The oilseed rape may put out a flower or two, and those flowers are so sweet they can stand a little frost. As the soil warms up, their roots will go foraging for nutrients to feed the growth in readiness for spring. Waterlogged soil cramps the roots, so we’ll see if our soil care was sufficient to keep the roots healthy from the wet of last month.

GRASS – The grass, with all its established roots and more robust soil structure, grows as soon as we are free of frost. The grass grew so actively through the winter, it’ll be interesting to see how it comes through. Actively growing grass will resist the frost, and we want it to leap into action, to feed the freshly calved cows.

COWS – The Spring cows are popping—first slowly, a few early birds, producing little calves that we nurse along. By the middle of the month, there are calves everywhere, the farm suddenly full of that distinctive blart of a calf making its feelings known. Our little crossbreed cows calve easily, and the calves are vigorous. The new Jersey crossbreeds in particular are bursting with life and vigour. It’s so satisfying to see a calf hit the ground, given a lick from its wondering dam, take that first breath (I notice myself holding mine till it does), then marshalling its unwieldy legs, teeters itself upright, then nudges its way around till it finds what? Aaaaaah, suck, slurp, that’s what’s I’m looking for. Then no more than twenty four hours together, to avoid a too-sad detachment, and calves go to join their herd-mates, little subdued creature, within a day skipping and bonded. The cows go to join their herd, again bruised then a welcome recovery, within earshot of their young.

Those first milkings are tough. Like people, their udders fill up with “nature,” that sore firmness that sets the milk flow off. There you are, battered and bruised by calving, missing your calf, sore and swelling udders and someone puts a milking machine on you. The older cows have seen it all and know the relief that milking brings. The first-time heifers can’t know, and it takes a little while to gain their trust (lack of trust expressed by some sharp little kicks, painful if you are in the way). By the third milking, they too learn to love it. In French, the milking parlour is the salle de traite, the treatment room, a place of relief and quiet intimacy.

Then there is the magic day when the cows go out to grass. They skip, buck, charge, and butt each other in delight, then settle down to the serious business of harvesting the delicious leaves.

CHEESE – In the cheese dairy, we watch to see how the milk is, and immediately that next milking after the ladies go out, the flavour and aroma changes, taking on notes reminiscent of a cow’s breath: warm, animally, and utterly gorgeous.

Now the work starts as at first a handful of fresh calved cow’s milk comes in, then a torrent. We finish off the jobs of the quieter time, cleaning and repairing racks, in readiness for the labours to come over the next few months.

Mary Quicke