In the verdant hills of the Swiss Emmental region, more than 3,000 feet above sea level, Bernhard Meier and his wife, Marlies Zaugg, are Emmentaler AOP cheesemakers in the oldworld tradition at the Käserei Hüpfenboden. In this area, husband-and-wife teams usually operate these small käsereien, or cheese dairies, sharing the daily work and routine while living adjacent to or upstairs from the facilities.

Meier and Zaugg are unusual since both are trained cheesemakers; normally just one person in the couple has formal training. They produce two wheels of wheels of Emmentaler every day, plus a few other cheeses and butter, which they sell locally. The 12 farmers who deliver milk twice daily to Käserei Hüpfenboden own the dairy and hire Meier and Zaugg to produce cheese, which is typical. After initial aging, cheeses are transported to the underground caves of Gourmino, a company just four miles north that ages wheels for up to 24 months, then negotiates sales and exports throughout Europe and beyond. This interdependence—among farmer, cheesemaker, and affineur—has been cultivated for centuries, and the union provides support and livelihood for all parties.

The Emme river valley—home to Käserei Hüpfenboden—is the birthplace of Emmentaler, as the name itself states. Thal is German for valley, but when spelling reform in 1902 simplified the written word to align with phonetics, thal became tal (just as thaler, which means “from the valley,” became taler). This mountainous region of west central Switzerland is in the Germanspeaking part of the country, though most inhabitants also speak French.

Dairy farming remains this region’s dominant economy. The Appellation d’Origine Protégée (AOP, previously known as AOC) for Emmentaler was set in 2000, establishing intense guidelines to ensure that Emmentaler AOP may only come from this region, in perpetuity. Without a doubt, original Emmentaler cheese is indeed Swiss. But what is it, exactly? And why are other cheeses with big holes made elsewhere in the world also called Emmentaler?

The answer is timely, as the European cheese union is lobbying aggressively to protect coveted cheese names with historic and location-based origins, such as France’s Brie and Camembert, England’s Stilton and cheddar, and Italy’s Parmigiano Reggiano and Pecorino Romano. A region’s topography—including water, soil, landforms, and more—naturally dictate the style of cheese produced there, and it’s no different with Emmentaler.

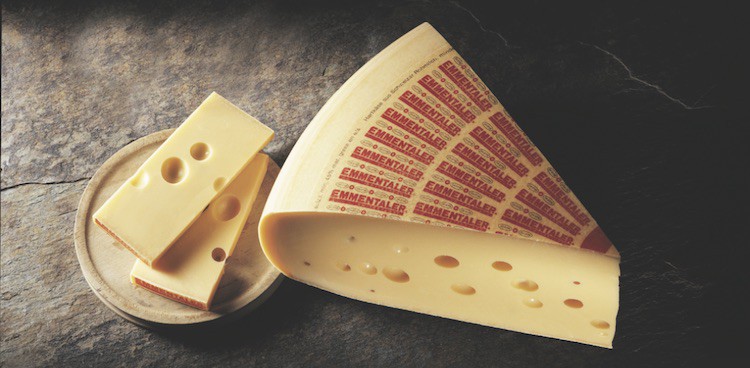

But the recipe for traditional Emmentaler is copied widely around the globe—the iconic holes, or “eyes,” dotting the cheese’s paste are recognizable from afar. Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery but what’s referred to ubiquitously as “Swiss cheese” is invariably based on the original Emmentaler AOP. Cheeses produced similarly to Emmentaler include protected curds such as Germany’s Allgauer Emmentaler and France’s Emmental de Savoie and Emmental français est-central; plus Norway’s Jarlsberg, Holland’s Maasdam, and any other holey cheese, including those created in the US and sliced in delis across the country. All are well-made, popular cheeses in their own right . . . but they’re not Swiss Emmentaler AOP. This is the distinction that’s near and dear to those proudly making this quintessential Swiss cheese as well as to those looking for the nutty, buttery, real deal.

Rules governing Emmentaler AOP production are strict. Milk is most important: cows must feed only on grass (or hay in winter) from pastures within designated areas of production. Each day, farmers deliver this unpasteurized milk to the käsereien, where it is heated gently in a copper-lined vat. A mix of traditional, proprietary cultures (mainly Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and Propionibacterium freudenreichii, all provided by a government-run lab) is added to the vat. The latter culture, commonly known as proprionic bacteria, feeds on lactic acid during aging to produce carbon dioxide, which in turn creates cherry- to walnutsized holes throughout the paste of the cheese. No preservatives or GMO ingredients are allowed at any stage of production.

The wheels at Käserei Hüpfenboden, however, are crafted a little differently. A small amount of whey—approximately half a cup—is removed from the vat during cheesemaking, incubated 48 hours, and used as the sole acidification for a new batch of Emmentaler (acting very much like the “mother” culture in sourdough bread). These cheeses bear a special label and are recognized by Slow Food as its Presidio’s Traditional Emmentaler, produced just as it has been for centuries.

The creation of Emmentaler AOP—from curd-cutting and “cooking” to hooping and brining—can be emulated (and it is), but results won’t be the same, as milk and cultures used in the production of Emmentaler are unique to the region. Each käserei’s wheels are labeled accordingly so even the consumer can pinpoint its origin, down to the dairy and make date. Most traditional dairies turn out four to eight wheels per day, each three-anda- half feet wide by ten inches high and weighing over 200 pounds. These are obviously not the simplest cheeses to heft, but they do age and travel well, which was the original intention.

Cooking the curd during production creates a harder, denser cheese suited for aging; rural mountain dwellers required long-lasting foods. Made at high altitudes in summertime, where cows feed on lush Alpine grasses and flowers, Emmentaler has been an important historical food source. After railroads were built in the mid-1800s, grains and other provisions were sourced easily and dairies in the low-lying Emme valley were able to churn out cheese year-round. Cheese has been a staple since the Middle Ages, though the number of Emmentaler makers has dropped markedly in the last century—from over 900 in the 1930s to 140 today. Still, Emmentaler production has increased, due to technological advances and the expansion of larger manufacturers as smaller käsereien shutter.

If you want to try Emmentaler AOP, your local cheese counter is the crucial link. Wheels—labeled with the symbol of the Switzerland Emmentaler Consortium, which features the iconic red cross of the Swiss flag—must be aged at least four months to meet AOP standards, but they may be aged up to 18 months. (Your monger may even have the Slow Food cheese from the Käserei Hüpfenboden for your picnic basket or fondue pot.) The older the wheel, the denser and deeper the flavor—all the better to savor with an exceptional bottle of wine.

Finding Emmentaler AOP in the US

Emmi is the largest affineur and exporter of Emmentaler AOP. Two are available in the US: a younger version, typically aged four months, with a softer, milder texture and taste; and wheels aged 12 months in Kaltbach caves halfway between Bern and Zurich (the latter are easily recognized by their black rinds, produced by the cave’s flora).

With two large cellars in Langnau, Gourmino is the last remaining affineur in the Emmental region. Its Emmentaler is available in the following ages: four to six months (mild); 12 months (surchoix); and 18 months (reserve); plus specially labeled Slow Food Emmentaler, aged 14 months.

Aged 16 to 18 months, Sélection Rolf Beeler Emmentaler comes to America in collaboration with Caroline Hostettler’s Quality Cheese of Fort Myers, Fla. It’s dense and intense, with a dark-brown rind and an ivory-colored interior yielding rich aromas and flavors.