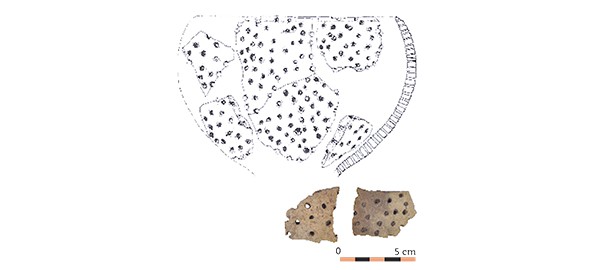

Archaeologist Peter Bogucki still remembers that “Aha!” moment in 1981 when he realized the mysterious fragments of perforated pottery he’d been uncovering for years at Neolithic farming sites in northern Poland could be evidence of the world’s earliest cheesemakers.

“I was looking at 19th-century sievelike ceramics used for cheese manufacturing at a friend’s home in Grafton, Vermont,” Bogucki said, “and on a long, rainy drive to Boston, it struck me that their similarity to those roughly 7,000-year-old hole-pierced potsherds was beyond coincidental.”

Bogucki, an associate dean for undergraduate affairs at Princeton University, was a key member of an international team investigating ancient Polish agricultural sites when he made the connection. (The area under investigation—Poland’s Kuyavia region—was quite familiar to him. He had started working in Poland as part of his PhD research at Harvard in the 1970s, but his interest in Polish prehistory arose during an undergraduate summer program in Kraków. To impress a young woman in the program with his archaeological knowledge, he suggested they visit a local museum. As a result, Neolithic farming cultures in Poland became the focus of his studies, and the young woman became his wife.)

About three decades after Bogucki’s road-trip realization, a team led by University of Bristol geochemist Richard Evershed suggested testing Bogucki’s cheese theory by sending 50 samples of small chips of potsherd fragments to fellow researcher Mélanie Salque for chemical analysis.

Tests revealed high levels of milk-fat residues on the artifacts. Since cheese is the only dairy product that requires straining, it was safe to assume these ancient ceramics may have indeed been used for that purpose. Early cheeses, the team theorized, were moist and pungent, resembling ricotta or fromage frais.

Evidence of the cheesemaking tools—potentially the world’s oldest—caused a sensation when revealed in Nature last December. But interest—and insights—didn’t end there. Researchers have since theorized that consuming cheese not only added an abundant protein source to the depressingly dull diets of our Neolithic ancestors, it also transformed our DNA.

“It’s amazing to think that cheesemaking might have come about as a result of the inability of ancestral farmers to digest fresh milk,” Evershed writes in an email.

Prior to the advent of cheese, humans typically became lactose intolerant soon after infancy. The domestication of cattle began about 10,000 years ago, and dairying only a millennium later. Genetically speaking, that means it didn’t take long for our ancestors to learn how separating curds from lactose-rich whey made an easier-to-digest product. But was there a deeper incentive (other than creating prototype cheeseburgers, of course)?

“One idea is that drinking [animal] milk… supplemented breast milk, and enabled mothers to wean their children more quickly,” says Mark Stoneking, an evolutionary genetics expert at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany (Stoneking wasn’t involved in the study). “Since most women aren’t fertile while nursing, the earlier a child is weaned, the sooner the woman will become fertile again and can thus have more children. So maybe the advantage was that it enabled women to have more children.”

Bogucki agrees, adding that Stoneking’s ideas about birth spacing “might have made cheese a particularly attractive resource to hunter-gatherers to draw them into the farming way of life. And farmers want to minimize birth spacing due to the need for agricultural labor that is undermined by high childhood mortality.”

There could have been an additional economic factor, Bogucki adds: Cheesemaking may have “provided an opportunity to transform an abundant but unwieldy resource (cow’s milk) into a storable and transportable substance (cheese).”

While none of these theories are yet verified as fact, what remains intriguing is the possibility that the cheese production pioneered by early Europeans bred a biological change in humankind, eventually leading to our ability to consume dairy products—and promote our love of cheese—well into adulthood.