It’s a balmy afternoon in Reggio Emilia, Italy, and I’m standing in a barn with a cow breeder named Marco Prandi, staring into his phone. “Allora cerchiamo la natività…” he mutters to himself while scrolling through Google Image search results. Thumbnail-size paintings of nativity scenes from artists in bygone eras whiz by until, finally, he lands on one. He enlarges the image. I lean in closer to examine the Natività di Cristo, a 15th-century Renaissance painting by Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Prandi points out the requisite characters surrounding chubby baby Jesus. “Mary… Joseph… the… come si chiama… donkey?” Finally, he zooms in on a gorgeous, crimson-hued bovine with majestic white horns and a tuft of fuzz on the top of her head. Then, he gestures toward the stables in front of us, where a cow nonchalantly munches on a pile of hay. “The same,” Prandi says—and he’s right. This cow looks like she was plucked from the Bethlehem manger of the Renaissance painter’s imagination and transported to a barn in the Italian suburbs.

Why does it matter if a 15th-century painter’s bovine muse happens to resemble the cow in front of us? If you believe that a cow is just a cow, it doesn’t. But we’re in the headquarters of the Consorzio Vacche Rosse, where passionate farmers and cheesemakers toil daily to voice the historical importance of this breed, to recount a saga involving destruction and redemption, as well as love, science, art, and cheese.

Reversal of Fortune

The saga begins around 1200 A.D., when 200,000 heads of this cow breed—known as vacche rosse (“red cows”) or Reggiana— roamed these plains. Set in the midst of Italy’s most productive swath of flat landscape, the breadbasket of Reggio Emilia harbored enough Reggiana cows to craft a whole lot of cheese; from their milk, Benedictine monks created a giant firm wheel—Parmigiano Reggiano—that could be aged for years. For a full seven centuries, Reggiana remained the go-to bovine breed in the Reggio Emilia region, its population stable, its milk transformed into epic wheels, its likeness painted by the masters.

But between 1945 and 1981, everything changed. The red cow population suddenly plummeted. The decrease was unprecedented: from 200,000 to just a few hundred. “That’s basically extinction,” says Andrea Berti, director of business development at importing company Atlanta Corporation. “To me, that’s one of the most interesting facts,” he says. “What happened there?”

The answer is at once simple and complex, a confluence of local factors and a microcosm of a global tragedy. Agriculture rapidly industrialized worldwide in the second half of the 20th century. For dairy farmers, that meant growth in scale; for breeders armed with new scientific tools, that meant pressure to select the most productive cows. Locally adapted, less productive breeds were replaced or crossbred until they’d effectively disappeared.1

By the end of the century, half of all Europe’s domesticated livestock breeds had gone extinct, and over 40 percent of those remaining were endangered. In Italy, change happened quickly. When World War II ended, people moved from villages to cities, from fields to factories. Farms that remained had to produce a lot more to survive. Instead of using Reggiana cows to pull tractors, farmers bought machines; instead of Reggiana milk, dairies opted for foreign breeds—like Holstein and Friesian cows—that could produce a third higher quantity.

With more milk, cheesemakers could meet the demand for Parmigiano Reggiano, which was growing in popularity. Its international fame eventually motivated them to solidify a Denominazione di Origine. Controllata , or DOP, in 1955, enshrining the use of raw milk and copper vats to distinguish the traditional cheese from industrial imitations. But the certification (today an EU-wide PDO), stipulated nothing about the breed of cow. And so the great Reggiana fell into obscurity.

Bouncing Back

In the early 1990s, faced with impending extinction, breeders of the few remaining red cows decided to take action. They formed the Consorzio Vacche Rosse, and founders were old stalwarts who had persisted over the years; today, “a number of them are dead,” says Luca Bedogni, a young employee of the consortium, “but they started to make a change. They convinced some younger farmers to breed this type of cow.” Marco Prandi, the consortium’s current president, comes from a long line of cow breeders in Reggio Emilia.

Like most of his peers, he grew up raising Holsteins. But his grandfather had raised red cows—he’d even won an award for the bovines at a local agricultural fair in 1933. As word spread of a movement to bring back the nearly lost breed, Prandi and his brothers joined in, gradually transitioning their herd back from Holstein to Reggiana starting in 1998.

They weren’t alone. Today the consortium has around 26 breeders. Some raise herds as small as 12; others have more than 200. Some breeders are as young as 26; others are over 80 years old. “Every farmer has a different history,” Prandi says. “Young, old, little, big, in the mountains, in the plains. But we all have one big love for these cows, love for the vacche rosse.”

A breed brought back from the brink because of love alone: It makes for a romantic story, but not a very realistic one. “Biodiversity is a beautiful idea,” Prandi admits, “but the breeder has a wife, has children. We don’t only work for the glory. We can save the breed only if we can make money back.” And to make that money back, breeders needed to prove that their milk was unique.

Thinking Different

With encouragement from the newly minted consortium, Italian researchers began examining the breed. They found that despite a lower yield, Reggiana cows’ milk contains a higher fat and protein content, as well as more calcium, phosphorus, ash, and citric acid. Looking at genetics, they discovered a super-high incidence of a genotype for a specific variety of casein protein in its milk—a protein proven to result in higher cheese yield and quality.

Physical traits in the cow were observed, too: a longer lifespan with less frequent sickness, and a well-developed rumen (the largest of its four stomachs) more conducive to grass feeding than grain feeding. Armed with this knowledge, it was time to make cheese.

The consortium teamed up with a Reggio Emilia–based animal research center and, along with financial help from the Ministry of Agriculture, launched a program in a local Parmigiano Reggiano production plant to separate milk from the Reggiana breed from milk of other breeds, making red cow–only wheels. The recipe was the same, following PDO guidelines—but the rules were stricter. First, Reggiana cows would eat more grass.

While 50 percent of a cow’s diet must be grass or hay when making Parmigiano Reggiano, that local, non-GMO forage makes up at least 90 percent of the Reggiana diet. Second, the cheese would be aged longer. While regular Parmigiano Reggiano can be sold after 12 months of aging, Vacche Rosse Parmigiano can only be sold after 24 months.

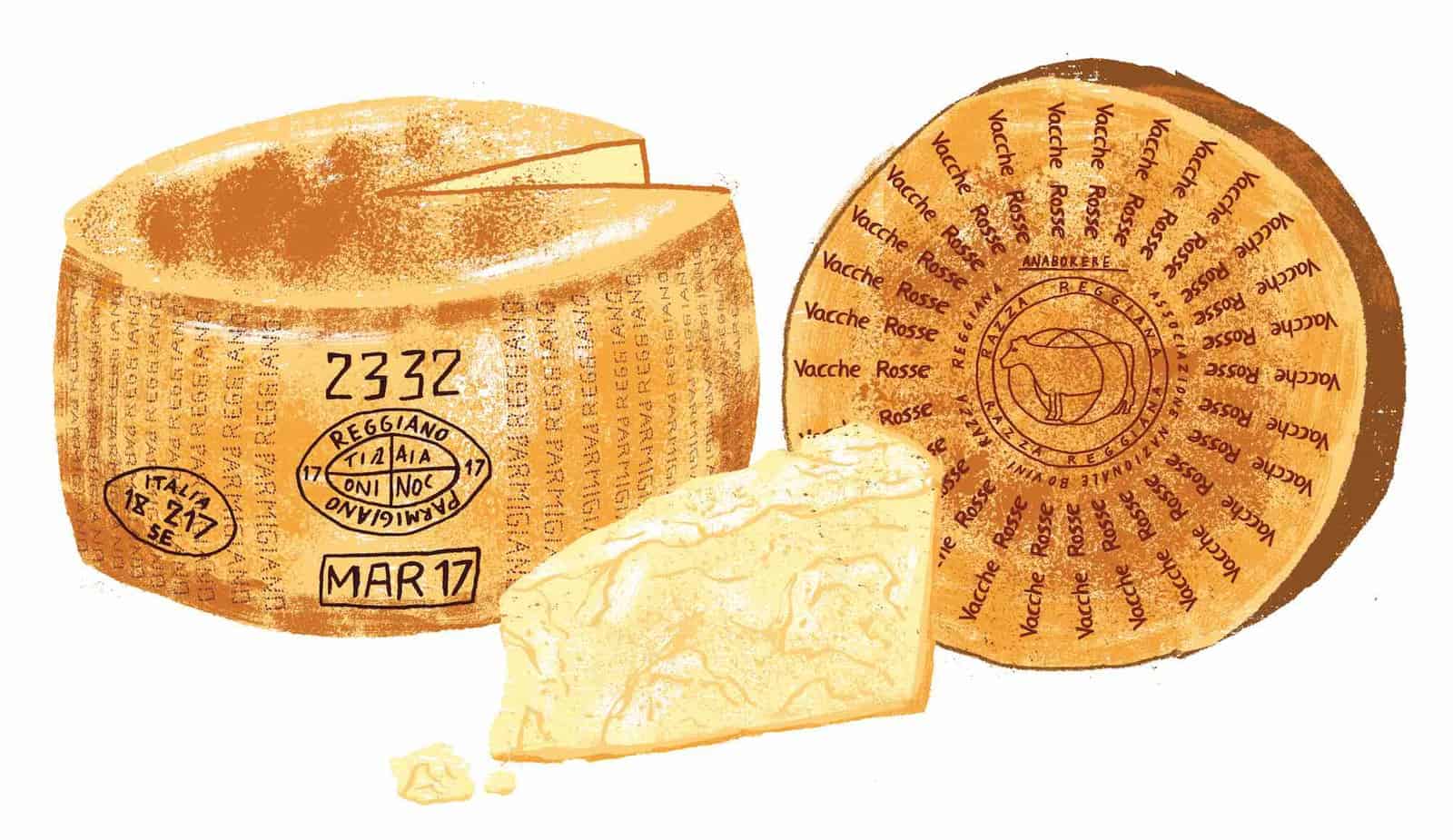

A grass-fed diet and longer aging go hand in hand. Wheels of this cheese—stamped with a red, cow-shaped logo surrounded by a spiral of “Vacche Rosse” on top, in addition to the PDO Parmigiano Reggiano stamp on the side—yield a different texture and flavor. “You get more of the grassy notes, and more complexity,” says Andrea Berti. “It’s much softer, more elastic.”

As the cheese progresses to over three years of aging, developing a deeper golden paste studded with amino acid crystals, it never becomes granular or pungent—but the flavor becomes more concentrated, the smallest morsel filling the palate with notes of butter and hay. “With its depth of flavor, it’s a longer, rounder cheese,” says Greg Blais, head cheesemonger at Eataly USA. “It just has more character.”

Going Global

With grass feeding, long aging, and a less productive cow, it’s no surprise that the Vacche Rosse Parmigiano Reggiano is more expensive by the time it reaches the cheese counter. (Today, while you might pay $20 to $26 a pound for a Parmigiano Reggiano, a Vacche Rosse version will usually retail for at least $30.) Blais, who has been selling the cheese since the late 1990s, remembers when his customers were initially turned off by the price. But he kept pushing the cheese, and eventually, people were coming back for it. “They just couldn’t deny the quality,” he says.

It’s the classic example of how you can either buy a lot of one thing, or a little of something good,” Blais adds. “Say you’re going to spend $10 on cheese. You’ll either spend it on a bowling ball–size piece of garbage, or something like this that you use a miniscule amount of, but [it] has such weight to it.” The monger has a handful of allegories to accompany his pitch. “It reminds me of those lembas from Lord of the Rings —the hobbit eats half of it and it’s the meal for like 20 weeks,” he says, or: “I had a piece of this cheese that I brought to three apartments I lived in. It outlasted, like, three leases.”

Blais’ strategy mirrors that of Marco Prandi, who says it takes two parallel methods to win people over. “We do tastings of the cheese, and we explain the difference. Taste the cheese, explain the difference. Taste, explain. Taste, explain,” he repeats, his body teetering left and right along with his gesturing arms. It’s working. In the past year, exports to the United States have increased 400 percent. “Now we have the problem that we almost finish the cheese!” Prandi exclaims.

The surcharge goes back to the source. In 20 years, the red cow population has crept back up from a few hundred to almost four thousand. Consortium members now earn a return for Reggiana milk that’s both higher in price and more stable than for conventional milk—an escape route from the economic treadmill that so often forces farmers to scale up or shutter. The benefits also echo back to local hay producers, who have a reliable outlet for their GMO-free grass.

A local breed nearly destroyed by agriculture’s globalizing forces is now recovering with the help of global consumers. Maybe it takes just the right formula—a mix of passionate makers, effective communication, and discerning turophiles willing and able to pay extra for quality—to bring back hope for livestock biodiversity.

The 15,000 wheels per year now being produced in two cooperative red cow consortium dairies pale in comparison to regular Parmigiano Reggiano’s 300,000 annual wheels—but that’s part of the charm. “We’re in a society where we want everything right now,” Prandi says. “The fact that the production is limited reminds people that you have to wait for the right time to have something good.”

From the relics of monks and painters to the wheels that wait 40 months to be cracked open, the saga of the red cow has a moral we can trace—and taste. Prandi sums it up: “We teach people the value of time.”