It’s not often that you meet a cheesemaker who has earned a PhD in economics as well as a law degree from the University of Wisconsin and who once worked for the U.S. senator who founded Earth Day.

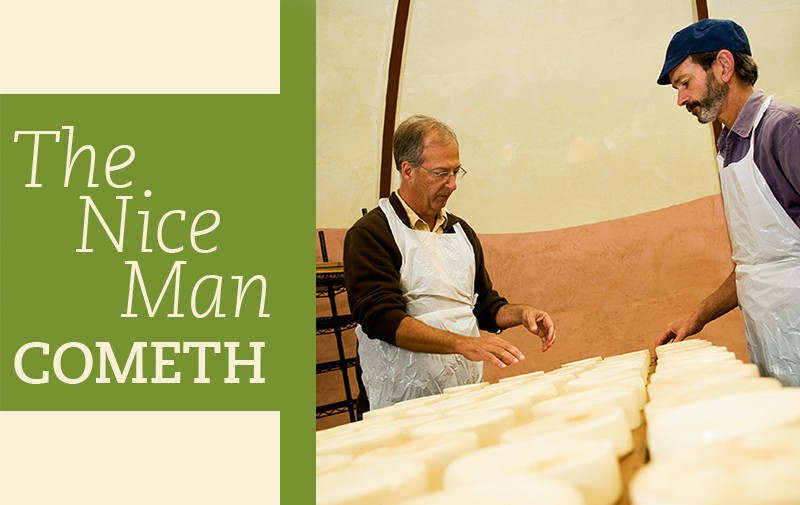

Then again, Bob Wills is not your average cheesemaker. Wills, now 54, didn’t start making cheese until he was 34. In fact, the thought never crossed his mind until the day he met Beth Nachreiner, whose parents happened to own Cedar Grove Cheese, a small creamery in southwest Wisconsin. The pair met while Wills was working as

an economist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Nachreiner was working in Wisconsin as a political advisor. Three years after getting married, the couple took over her retiring parents’ cheese factory in the tiny town of Plain, and Wills left behind a promising academic career as a research associate at the University of Wisconsin.

He hasn’t looked back.

“I never really liked the academic world. I always had a sense of wanting to own my business, although why, I don’t know—it’s a crazy and stressful thing to do,” he says laughing. “But the truth is, I can’t imagine doing anything else.”

In Wisconsin, home to more than 1,200 licensed cheesemakers and 124 cheese plants, making cheese is usually a family profession. Many hail from second-, third-, and even fourth-generation cheesemaking families. Here in America’s Dairyland, working as a cheesemaker is not seen as merely a job, it’s a way of life—and often a tough one, full of long, weird hours. Most cheesemakers leave for work while their neighbors are still sleeping and return home twelve or fourteen hours later, six days a week. To top it off, very few cheesemakers ever get rich. Wills admits he’s still waiting to strike it rich nearly two decades into the journey. But Wills, like most who enter this hallowed profession, does it for more than just a paycheck.

“It’s a great lifestyle and a good way to raise kids,” says Wills. He and his wife just sent their oldest son, Bo, off to college. Daughter Emma is a senior in high school, while son Owen, 12, is a seventh-grader. “Plus, people seem to appreciate the creativity of what we’re doing here at Cedar Grove. We have fun, we’re open to new ideas, and I get to work with some of the most exciting people in the industry every day.”

That’s because Wills, in a strategic move one might expect from a button-down former professor, decided eight years ago to open his specialty cheese plant to farmers interested in having a custom product made from their milk as well as to up-and-coming cheesemakers looking to rent a cheese vat to experiment with new recipes.

An absolute delight

Today, Wills, a Master Cheesemaker in his own right (Wisconsin is the only state to both license its cheesemakers and offer an advanced certification program), has helped launch at least seven cheese brands, including, arguably, the most famous cheese ever to come from Wisconsin: Pleasant Ridge Reserve, crafted by Mike Gingrich of Uplands Cheese Company. Gingrich produced his award-winning Beaufort-style cheese at Cedar Grove for four years before building his own farmstead cheese plant in 2004. But Pleasant Ridge Reserve isn’t the only award-winner to come out of Cedar Grove. Of the 88 awards captured by Wisconsin cheesemakers at the 2008 American Cheese Society Competition, 14 were won either by cheesemakers mentored by Wills or by cheeses currently made at Cedar Grove.

Take Bleu Mont Dairy’s Willi Lehner, for example. A second-generation cheesemaker, Lehner rents space at Cedar Grove to make his award-winning cheeses, including his Bandaged Cheddar, named in the September 2008 issue of Wine Spectator as one of “100 Great Cheeses” of the world. Wills says renting his cheese plant to outside cheesemakers during off-production hours benefits everyone. “I learn something from every one of the people making cheese at my plant. Cheesemakers like Willi—who’s always trying something new—are an absolute delight to work with. They constantly teach me new things, and I offer advice when asked. It’s definitely a two-way street.”

Because of stiff competition, strict environmental standards, and confidentiality issues, very few cheese plants across the nation open their facilities to other cheesemakers. Nobody knows that better than Mike Gingrich. In 2000, Gingrich and his wife, Carol, decided to experiment with making a seasonal, alpine-style cheese from the milk of pasture-grazed cows on their farm near Dodgeville, Wisconsin. The initial investment of building a farmstead plant with an unproven product was intimidating, so instead they approached area cheesemakers to see if any would be willing to rent out their plant for a few hours a week. Wills was the only cheesemaker to say yes, and the endeavor has since paid off for both parties.

“I can’t imagine how we could have gotten started in this business without Bob’s cooperation,” Gingrich says. “For the first four years we made cheese at Cedar Grove, we doubled our production every year and put all of our profits back into the business so we could keep growing. There’s no way we could have done that if we had a mortgage to pay.”

The Big Cheese

Renowned as both a mentor and an incubator for up-and-coming cheesemakers, Bob Wills is not only an award-winning Master Cheesemaker in his own right, but as the head of Cedar Grove Cheese in Plain, Wisconsin, he’s helped build the brand for dozens of award winners.

Here’s a sampling of some of the companies Wills has partnered with since 2000:

- Uplands Cheese Company, Dodgeville, Wis.: Arguably Wisconsin’s most famous cheese, Pleasant Ridge Reserve won the American Cheese Society’s Best of Show in 2001 and 2005 and was named the U.S Championship Cheese in 2003. Cheesemaker Mike Gingrich crafted this beauty at Cedar Grove for four years; later building his own farmstead cheese plant.

- Bleu Mont Dairy, Blue Mounds, Wis.: The New York Times crowned Willi Lehner earlier this year as the “rock star of the Wisconsin artisanal cheese movement.” Lehner crafts several cheeses at Cedar Grove, then moves the cheese to a 1,600-square-foot underground aging cave he built on his farm in Blue Mounds.

- Nordic Creamery, Westby, Wis.: Cheesemaker Al Bekkum launched his own cheesemaking brand in 2007 and makes several cheeses, including two American Original mixed-milk cheeses, Capriko and Feddost, at Cedar Grove. Bekkum won a blue ribbon in his first showing at ACS in 2008.

- Wisconsin Sheep Dairy Cooperative, Strum, Wis.: Wills makes the award-winning Mona and Dante sheep’s milk cheeses for this farmer-owned cooperative, consistently winning awards at national and international competitions.

- Otter Creek Organic Farm, Avoca, Wis.: This nearby organic farm partners with Cedar Grove to craft seasonal organic cheddars, winning a third-place ribbon in the company’s first showing at the 2007 ACS competition.

- Sugar River Cheese Co., Deerfield, IL.: Wills makes certified-kosher cheeses for this company, winning a second-place ribbon at the 2006 ACS conference.

- Next Generation Organic Dairy, Mondovi, Wis.: Wills makes organic, raw-milk cheeses for a group of dairy farmers in north central Wisconsin, adding value to their operation.

Empowering farmers

Wills, ever-modest, downplays the impact he’s had on start-up cheesemakers such as Gingrich. He instead focuses on the bigger picture: “I’m interested in finding ways to empower farmers and partner with others to better market and distribute Wisconsin cheese. Ultimately, life is about people. It’s about relationships and helping people change the way they look at their food.”

In a testament to his personal philosophy of helping others, he harbors no ill will when some cheesemakers, such as Gingrich, leave Cedar Grove and graduate to their own farmstead plants. Instead of viewing it as losing business, he simply finds another opportunity to partner with a neighbor and create another start-up cheese business. “Something always comes up,” he says, smiling.

Lately, that something is a surge in demand from dairy farmers looking to add value to their farms by hiring Wills to craft specialty cheeses specifically for them. One example is the Wisconsin Sheep Dairy Cooperative, based in northwestern Wisconsin. This farmer-owned cooperative pools its milk and ships it to Cedar Grove, where Wills crafts two award-winning cheeses: Dante, an aged sheep’s milk cheese with a buttery, nutty flavor, which took Best in Class at the 2006 American Cheese Society Competition; and Mona, a mixed-milk cheese made from sheep’s and cow’s milk and aged to produce an appealing, robust flavor. The cheeses consistently win ribbons at national and world competitions.

Wills also crafts an array of specialty organic cheeses for Next Generation Organic Dairy of Mondovi and Otter Creek Organic Farm in Avoca, Wisconsin. in addition, he produces a line of certified-kosher cheeses for Sugar River Cheese in Deerfield, Illinois. His next customer might just be a neighboring start-up farmer that has a herd of water buffalo and is interested in making fresh mozzarella at Cedar Grove.

His secret weapon

In all, Wills and his 35 employees—including his “secret weapon,” cheesemaker Dan Hetzel, who has worked fifty-two years at Cedar Grove—craft about 4 million pounds of cheese a year. Wills acts as the wizard behind the cheddar curtain, always coming up with new varieties and overseeing production with a core group of employees loyal to his mission of sustainable production and environmental leadership.

In fact, Wills was the first cheesemaker in the United States to label his cheese as rBGH-free in 1993. He was on the cutting edge of the controversy related to bovine growth hormones and genetically modified foods, and to this day Wills does not feel comfortable using milk that comes from cows given artificial hormones. All farmers who ship milk to Cedar Grove commit to rBGH-free milk production. In addition, Wills is committed to exceeding the standards for wastewater treatment and has sought out innovative methods to run his plant in an energy-efficient manner.

Cedar Grove’s own cheeses are mostly specialty and organic varieties, such as flavored Monterey Jack, Cheddar, Colby, Havarti, and Butterkaese. Between different cheesemakers coming and going, and Cedar Grove pumping out its own cheese, the plant is rarely idle. One begins to wonder when Wills has time to develop new varieties, such as his latest line of layered cheeses. Cedar Grove’s Cumin & Cloves Dutch Style captured a Best of Class award at this summer’s American Cheese Society Competition in Chicago. The cheese is striped with a layer of spices through the center of the wheel, a rich, nutty organic cheddar. Rounding out the new line are Cracked Fennel in Organic Cheddar, Fenugreek in Butterkase, Rosemary in Organic Cheddar, and a new favorite: Naturally Smoked Cheddar with Smoked Salmon & Dill.

Wills crafts all of his cheese with an eye to sustainability. In 2007, Cedar Grove Cheese, along with 13 dairy farms who supply milk to the plant, completed certification with the Midwest Food Alliance in Minneapolis, earning distinction as the first food processor in the United States recognized for its commitment to green technology. The Midwest Food Alliance evaluated several aspects of the businesses, such as environmental practices, labor standards, and animal welfare issues.

Wills says his dedication to finding innovative ways to ensure the plant operates in an environmentally friendly manner stems from his childhood. Growing up in Brookfield, Wisconsin, Wills was taken by his father, a newspaper man, each year on a summer trip to the Boundary Waters, a region of wilderness straddling the Canada-United States border just west of Lake Superior. “I learned that it’s all about the water, plain and simple,” he says. He continues to apply that childhood lesson in every aspect at Cedar Grove, from the way he chooses to treat his wastewater to the way he powers his plant.

This philosophy is part of the reason Wills and the rest of Wisconsin’s cheesemakers are seen more and more as innovation leaders in a state once better known for its foam cheese heads and commodity cheddars than its specialty and artisan varieties.

The Living Machine

Wills is committed to recycling as well as reducing Cedar Grove Cheese’s energy usage. In 2000, he implemented an earth-friendly and cost-effective way to handle the 7,000 gallons of wash water used daily in their facility. Named the Living Machine, this elaborate greenhouse system mimics the water cleaning power of wetlands using natural microbes and plants. At the end of the complex process, wastewater is filtered into clean water and returned to the ecosystem via nearby Honey Creek.

The Living Machine consists of ten tanks, each extending four feet underground and holding 2,600 gallons of water. Tanks are connected by four-inch pipes beneath the ground; gravity causes water to flow between them. With two closed aerobic tanks, a series of open aerobic tanks, a settling tank, and a host of filters—all surrounded by tropical wetland plants that can grow as much as six inches per week—the ecosystem can some days resemble Little Shop of Horrors.

“The natural process of treating our wastewater helps us remember that what goes down the drain matters,” Wills explains.

Wills also oversaw an expansion project to relocate Cedar Grove’s cheese-aging facility from a leased space nine miles away to a new 1,800-square-foot cheese cave attached to the plant in Plain, Wisconsin. The new space is designed to use energy from the plant’s whey chilling unit.

“In addition to considerably more efficient cooling, we eliminated the time and fuel use of moving people and product out of town,” Wills says.

The main room is a dry-aging chamber for sheep’s milk cheeses the plant crafts for the Wisconsin Sheep Dairy Cooperative. Additional aging rooms house dozens of varieties of cheeses made at Cedar Grove, of which more than 60 percent are organic.

“We take pride in preserving old-world Wisconsin tradition and standards in our cheesemaking,” Wills comments, “as well as being at the forefront in organic production, grass-based dairy promo- tion, water treatment, and product innovation.”

The time is now

Wills compares the recent surge in Wisconsin’s specialty and artisan cheese production to similar periods in history when a confluence of actors would meet on one stage to challenge one another and make each other better. Wisconsin cheesemaking has entered one of those periods.

“There are pivotal times and places for the cheese industry, and this period in Wisconsin is one of those times,” he says. In the past six years, the state of Wisconsin, including its Dairy Business Innovation Center, the Wisconsin Specialty Cheese Institute, and Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board, has focused on helping Wisconsin cheesemakers create specialty and artisan cheeses, boosting their bottom lines as well as the public image of Wisconsin cheese.  Wills is even bold enough to compare the current lineup of Wisconsin cheesemakers, who together are crafting more than 600 varieties, types, and styles of cheeses, to Keats, Shelley, and Byron, or the American Beat writers in the 1960s, or London musicians circa 1750 to 1800.

Wills is even bold enough to compare the current lineup of Wisconsin cheesemakers, who together are crafting more than 600 varieties, types, and styles of cheeses, to Keats, Shelley, and Byron, or the American Beat writers in the 1960s, or London musicians circa 1750 to 1800.

“I’ve got Sid Cook (Master Cheesemaker of Carr Valley Cheese) just down the road from me,” Wills says. “In fact, at one time, there were three Master Cheesemakers all living within a block of each other near here. It becomes a friendly competition. We watch what each other is doing, and we strive to be better. In the past few years, the state’s dairy infrastructure has really come together, and now consumers see the potential for American cheeses to be as good or better than their European counterparts.”

And, he continues, “All of this leads to cheesemakers stretching themselves to capture the public’s imagination. We’re generating more creativity and energy among all of us than we could ever do on our own. It makes each one of us better.”