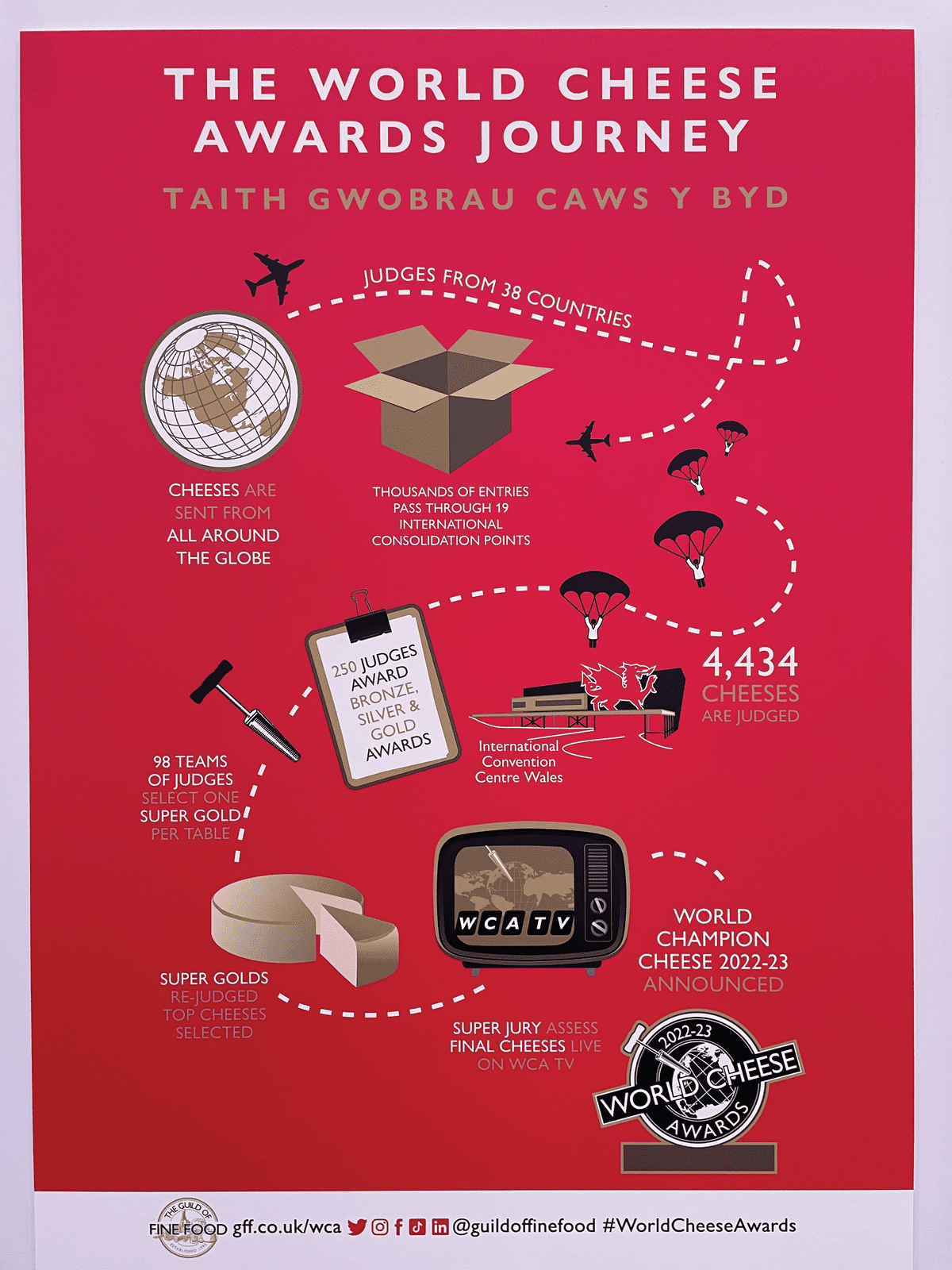

The rich sound of a Welsh choir fills the corridor as my fellow judges and I file into the exhibition hall at the International Convention Center Wales for the 34th annual World Cheese Awards (WCA). Wearing our official aprons, which match the color of the huge red dragon sculpture outside the building (the red dragon is the symbol of Wales), all 250 of us gather for a group portrait before dispersing to find our assigned tables and meet our teammates. This is my second time as a WCA judge, and although I know what to expect, the enormity of the whole enterprise still leaves me awestruck. Arranged on the tables are 4,434 cheeses from nearly every corner of the globe, and the people in the room are a veritable who’s who of the international cheese world—some of whom I feel lucky to now consider friends.

At table four, I meet Thibault Dupas, head cheesemonger at La Fromagerie du Louvre in Paris, which opened in June. Having made cheese in Australia and worked at the Fine Cheese Company, in Bath, UK, he speaks perfect English, and I’m grateful I don’t have to roll out my rusty French. He also knows a great deal about cheese, which he conveys in a friendly, collaborative way as we set about our task. The judges have been briefed by John Farrand of the Guild of Fine Food (GFF)—the UK-based organization that hosts the WCA—to score each cheese on its own merits, and to be mindful that some cheeses will have traveled thousands of miles and may be in less-than-optimal condition. We have also been advised that if a cheese seems “off,” not to score it at all.

Thibault and I have 43 cheeses to taste and score (each table has 40 to 45), and while some tables have three judges, it’s just the two of us. I’ve been assigned the role of coordinator, which means I’m responsible for entering the scores into an iPad. He suggests unwrapping all the cheeses before we begin—a smart move since many of them are encased in plastic and need to breathe for their flavors to emerge. He deftly opens the larger wheels with a two-handled cheese rocker knife, since the best- tasting part of these will be near the center.

Some of what’s on the table is easily recognizable as goudas, manchegos, and bries, but each cheese is numbered; we don’t know the makers or the countries of origin. The scoring system is straightforward, and we are expected to come to a unanimous decision. Out of a possible 35 points there are five each for appearance, body and texture, and aroma, and 20 for taste and mouthfeel. Less than 23 points results in no award; 23–26 wins a Bronze, 27–30 a Silver, and 31–35 a Gold.

The first cheese is a fresh chèvre log. We suspect it’s European because the flavor is more goaty than most American chèvres, and since it’s a fine example of the style, its score adds up to a Silver. We each take a spoonful of the second one, a lactic-set cheese in small cups, and immediately spit it out—it has spoiled. We taste on through the rest of the cheeses, leaving the blues for last, and cleansing our palates between bites with apple slices and plenty of water. Two more cheeses are deemed unfit to eat and are not scored. We chat with judges at neighboring tables about how sad it is when despite cheesemakers’ best efforts, cheeses arrive to the awards in bad shape—a problem exacerbated by the current transit slowdown.

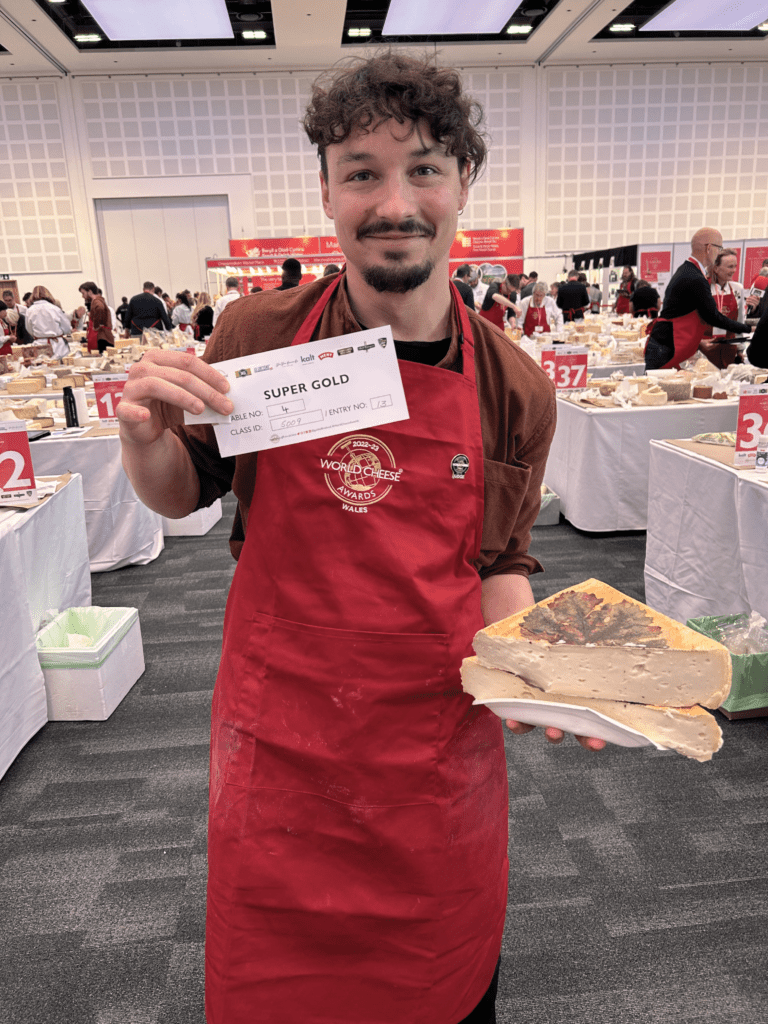

Our final task is to choose one Super Gold cheese to advance to the next level of judging. We have just two Golds on the table—a striking goat’s milk taleggio- style cheese, washed in white wine and adorned with a grape leaf, and a creamy blue. The former is a no-brainer choice, and Thibault carries it to the Super Gold table in the far corner of the room. When this first round of judging is finished, the table will hold 98 Super Golds, which the Super Jury—made up of 16 cheese experts from as far away as South Africa and India—will whittle down to the 16 cheeses that will go to the finals.

First, however, there is the judges’ lunch, which includes a Ukrainian cheese tasting (more cheese!) My favorite is an aged gouda style, which has the characteristic crunch of tyrosine crystals. The WCA

was supposed to be in Kyiv, Ukraine, this year, and it is the first time that Ukrainian cheeses have entered. Out of 39 cheeses, 13 of them ultimately win awards, including a Gold and a Super Gold. The slogan proclaimed on T-shirts and tote bags handed out at the Ukrainian cheese booth in the exhibition hall, says “Freedom Tastes Great,” and I’m thrilled to have one of each to bring home.

At 4 p.m., a sizeable crowd gathers in the convention center auditorium for the finals, which are emceed by Nigel Barden, a longstanding contributor to BBC Radio London and a gregarious champion of good food and drink. The 16 members of the Super Jury, which include Whole Foods VP of Specialty Cathy Strange, and former culture contributor Carlos Yescas, are introduced and take their seats at a long table onstage. As if he is presenting fine art objects, Barden’s sidekick, bowler hat–wearing cheese expert Charlie Turnbull, brings out each of the 16 finalist cheeses in turn to sing its praises; there are 10 from Europe, four from the UK, and one from the US—Greensward, a bark-wrapped cow’s milk wheel from Murray’s Cheese. The jury then votes by holding up numbered placards with seven as the top score. Excitement builds as an Italian gorgonzola dolce garners 98 total points, only to be topped by Switzerland’s Vorderfultigen Gourmino Le Gruyère AOP surchoix with 103. The final cheese is a French buffalo milk tomme, and when its score of 94 is tallied, there’s a whoop at the back of the auditorium. It’s from Joe Salonia of Gourmino, which ages the cheese, and Denis Kaser of Le Gruyère AOP, who gleefully run down to the stage, knowing their cheese has triumphed.

Later, at the festive judges’ dinner, Farrand announces that the 2023 WCA will be in Trondheim, Norway, and thanks the Welsh government for its hospitality. There are impassioned, grateful speeches from Salonia, Kaser, and Patricia Michaelson, founder of the UK’s La Fromagerie cheese shops, who is clearly stunned to receive the GFF’s Exceptional Contribution to Cheese Award. “It’s written on the walls of caves,” Michaelson says about how long humans have been making cheese. The finished products win the awards, but everyone in the room is a testament to the fact that it is people, working in harmony with the land, the animals, and each other, who have for centuries been responsible for creating what the late artisan cheese advocate Anne Saxelby called “this transcendent, joy-provoking food.” The joy around us is palpable, and the magic of the connections made through cheese puts us all in the winners’ circle.

Note: Cheeses from the 2022 World Cheese Awards will be featured in the 2023 Best Cheeses Issue.