It’s 2019: Are you itching for a makeover? Yearning to reinvent yourself? If so, perhaps your new fashion icon should be cottage cheese. To see what we mean, browse the website of Muuna, a recently launched cottage cheese brand. Between splashes of bright color and snapshots of laughing millennials, you’ll find a video of a young woman in pink workout garb. As blurry background figures pedal stationary bikes, she pops a spoonful of cottage cheese into her mouth. Her face transforms: Skepticism gives way to surprised satisfaction. The tagline is “Bye Bye, Boring.” It’s labeled gluten-free. There’s even a limited edition pumpkin spice flavor.

“We’re here to disrupt cottage cheese,” says Gerard Meyer, Muuna’s CEO. Indeed, the vibrant world Muuna depicts, in which beautiful people gather to giggle around cottage cheese cups, seems a bit like an alien dimension—especially for those of us who grew up shunning the snack. “We’re doing something that’s never been done in cottage cheese,” Meyer adds. “How revolutionary, to actually show people enjoying it?”

Country Shacks and Jell-O Salads

At its essence, cottage cheese is old-fashioned. Quite literally: It dates back eons. Some of the earliest cheeses ever made were likely similar. That’s because the traditional recipe is simple. Fresh milk is left to naturally separate, a fatty layer of cream floating to the top. The cream is skimmed off and the remaining lowfat milk is left to ferment, or “clabber,” its native bacteria producing acids that cause it to curdle. The curd is cut, gently heated, and mixed. Whey is removed and the curds are rinsed in cold water, helping them firm up before they’re drained. Until this point, the process is pretty similar to making a rustic wheel of cheese—but instead of being formed and pressed, the mass of curds is crumbled and mixed, or “dressed,” with cream.

Dairypure Cottage Cheese

“It’s a farmhouse style,” says Sue Conley, co-founder of California-based Cowgirl Creamery. “In the early days, family farms would skim off the cream to make butter, and it was a way for them to use the nonfat milk by making a simple cheese.” Several variations harken back to the Old World, but the first stateside reference to “cottage” cheese dates to an 1831 article titled “Country Lodgings” in Godey’s Lady’s Book magazine. Visiting rural homes, writer Miss Leslie critiqued “not inviting” spreads observed during teatime: “paltry cakes,” “dried beef,” and “cottage cheese.” Its name is thought to reference its origin: cottages in the countryside.

The provincial cheese stayed out of the spotlight until the wartime years of the 20th century, when consuming the creamy curds went from rural habit to patriotic duty. During World War I food shortages, cottage cheese was promoted as a protein source. “Eat more cottage cheese; you’ll need less meat,” urged a wartime USDA poster. The sentiment returned during the second World War, during which sales of the cheese increased five-fold.

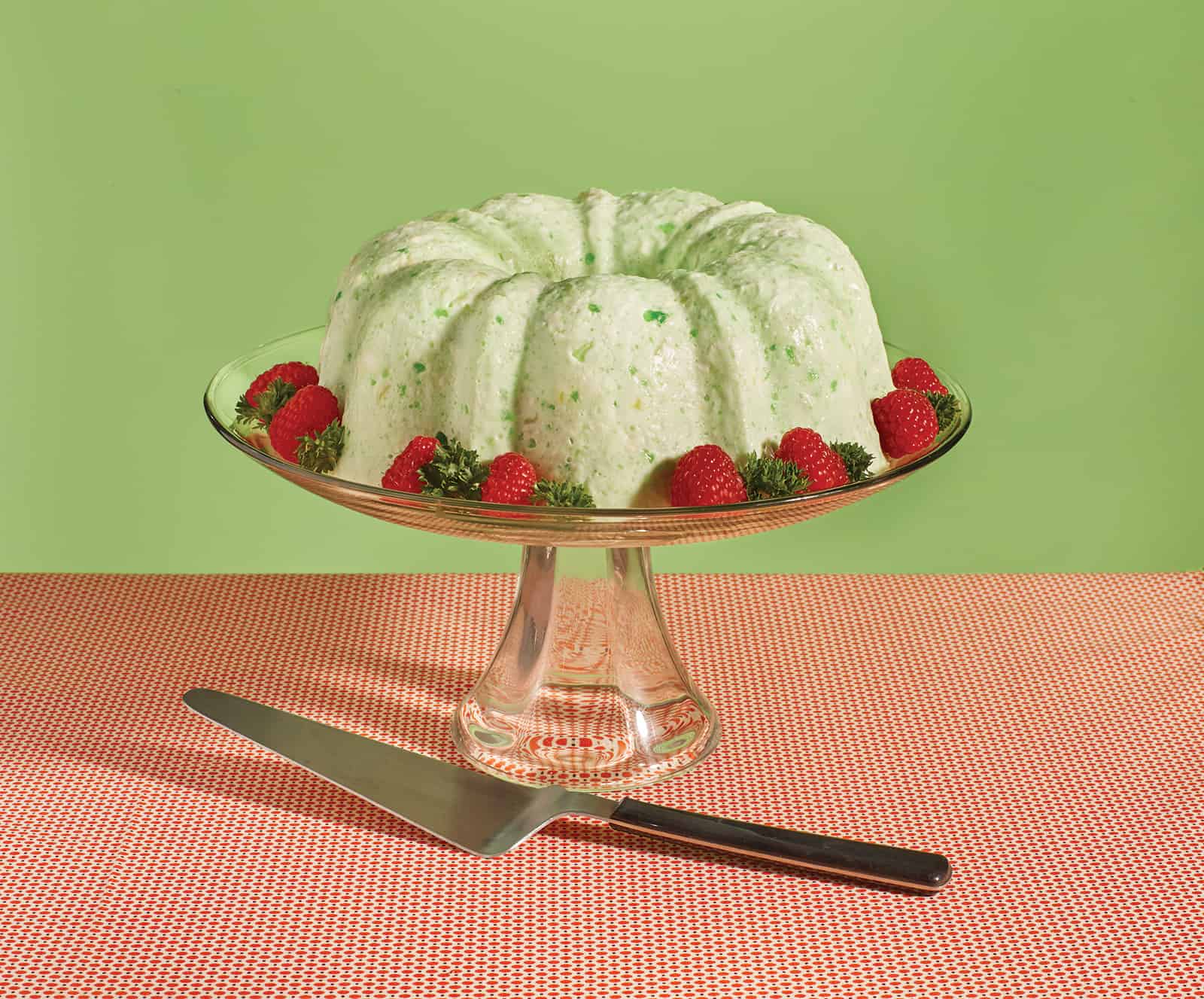

A post-war explosion in population—and dairy demand—deepened the need for a reliable protein source that was cheap to produce, and industry giants responded accordingly. To avoid the tediously slow clabbering process, they started taking shortcuts, adding rennet to coagulate milk faster, and heating the curds to a higher temperature. This rendered them tougher, while eliminating the complex flavors created during slow fermentation. Nonetheless, the chewy cheese became a household staple, central to the iconic Jell-O salad: a mixture of the namesake gelatin (usually lime), cottage cheese, mayonnaise, and canned pineapple formed in a Bundt pan.

Sans the flavor and texture that once made it so delicious, cottage cheese had one lingering point of appeal: Since the curds were traditionally made with lowfat or nonfat milk, the cheese’s fat content could be easily modified by altering the dressing. Fatty cream traditionally used to dress curds could be swapped out for milk thickened with cornstarch and, later, gums and stabilizers. And so cottage cheese became a weight–loss food. The lumpy white substance alongside a lean hamburger patty, a sad lettuce leaf, a pale tomato, and slimy canned peaches: This was a classic 1970s diet plate. Some even went so far as to follow the “cottage cheese diet,” a fad regime mandating cottage cheese—yes, exclusively cottage cheese—for three meals a day.

Yet after peaking at more than five pounds per capita in 1972, annual consumption of cottage cheese plummeted to about two–and–a–half–pounds in 1996, with a slight decline each year since. So what happened? The short answer, says Meyer, is nothing. “The category has been comatose; it’s been frozen in time for 40 years.” The cheese remained a staple side hustle for large dairy companies, made with surplus milk and sold in large tubs. But as lowfat fads faded, nobody gave thought to a rebrand—cottage cheese was relegated to Technicolor memory, forever linked with Jell-O and Bundt pans in our collective conscience.

Cooler Cultures

To understand the scale of stagnancy, just look at a similar product that embarked on a starkly different trajectory. Back in the 1970s, yogurt was marketed in a similar way to cottage cheese: large tubs, plain flavor, bland branding. But since then, new yogurt brands have popped up, introducing innovations like single-serve packaging, flavor blends, and fruit on the bottom.

Green Valley Creamery Organic Cottage Cheese

Yogurt makers began offering convenience and choice. All members of the household could eat different flavors, and kids could carry it in a lunchbox. “As a kid, you couldn’t have paid me to eat plain yogurt,” Meyer says. “But if you put blueberries, sugar, and all that in it, I ate it.” Today 90 percent of yogurt is sold in single-serve size, he adds; by contrast, 90 percent of cottage cheese is still sold in big tubs.

Yogurt companies also focused on nutrition, but unlike cottage cheese makers, they evolved their message in tandem with prevailing health trends. As lowfat diet fads lost traction and a protein craze emerged, yogurt companies began focusing on thicker, protein-rich blends. As probiotics came into the spotlight, yogurt packaging began boasting billions of bacteria. And it worked. Forty years ago the yogurt business was less than half the size of cottage cheese’s, according to Meyer—now it’s eight times bigger.

But cottage cheese can have protein and probiotics, too. In fact, it usually has more protein than yogurt. It also tends to have less sugar. “Here’s this high-protein, nutrient-dense superfood that really isn’t growing from a category standpoint. Why is that?” says Jesse Merrill, co-founder and CEO of grass-fed cottage cheese company Good Culture. After spearheading marketing campaigns for successful brands like Honest Tea, Merrill was looking to launch a new business; he perused grocery store aisles in search of an idea. “It became clear there had been little to no innovation in cottage cheese,” he says. “But why can’t you eat cottage cheese in a single-serve cup? Why can’t you put fruit on the bottom? I saw a massive opportunity to put a cottage cheese out there that was more relevant to today’s shopper.” Launched in 2015, Good Culture now stocks grocery shelves with containers of cottage cheese that look so much like yogurt, they likely have dairy aisle shoppers doing double-takes.

A container of Muuna looks similar, and for the exact same reason. “Our consumer, the average cottage cheese consumer, is the heavy yogurt consumer,” Meyer says. Market research indicates that the most frequent cottage cheese consumers tend to skew older, but those who dabble in cottage cheese once or twice per year look identical to average yogurt consumers: female, college educated, and slightly younger. “Fifty percent of people who buy yogurt buy cottage cheese,” Meyer adds. “They just don’t buy it very often. We want them to see that it’s better than yogurt, and we want them to buy it more often.”

Good Culture Cottage Cheese

The goal of both companies is to align cottage cheese with yogurt’s current trends. Their versions are thick and creamy—Meyer calls Muuna the “Greek yogurt of cottage cheese,” while Merrill boasts that you can hold a cup of Good Culture upside down and nothing drips out. (“That’s our quality test,” he says.) Both products contain probiotics and claim proprietary production practices that elevate protein content, and both have nailed a marketing strategy on par with the times—a clean label and rejection of stabilizers, gums, and other unpronounceable ingredients.

“Our product is 100 percent on-trend,” Merrill says. “Those consumers—millennials, younger Gen Xers—we’re marketing in a way that’s relevant to them, through really strong branding, through fun marketing.” Social media influencer campaigns, sampling at events, a mighty PR campaign: This is what disruption looks like.

Back to the Cottage

Yet when it comes to popularizing cottage cheese, it’s not all about beautiful people and portable packaging. Makers know that taste matters, too. And in cottage cheese, taste requires patience.

“It’s not so easy to make well,” says Conley, citing the two-day process her team uses to make Clabbered Cottage Cheese at Cowgirl Creamery. They do it the old-fashioned way. The cream is skimmed off and the milk cultures for about 14 hours. Curds are heated slowly over an hour while being stirred, and instead of artificially thickened milk, Cowgirl’s dressing is made from a mix of cultured milk and cream.

Originally conceived in the late ’90s when the creamery was just starting up, the cheese required such a tedious production cycle that only a few hundred containers could be made per week. “It became a cult cheese,” Conley says. After taking a hiatus for several years, Cowgirl upped production capacity and brought it back in 2018—but don’t expect fancy fruit or portable tubs. It’s likely similar to what you would have found in those cottages of yore: full fat, complex flavor, and probiotics—“without have to brag about it,” Conley says, chuckling.

Traders Point Creamery Cottage Cheese

In Indiana, Traders Point Creamery makes cottage cheese with a similar philosophy. Using just two strains of bacteria and no rennet, cheesemaker Jonathan Love lets the milk acidify for 12 to 15 hours before hand-skimming it. The cream he skims off, which is also fully cultured, becomes the dressing he’ll later mix back in. “It’s not just curds sitting in milk,” he says. “With the acidified dressing, it tastes more like cheese. It doesn’t taste like the cottage cheese people grew up eating.”

Harkening back to those older methods also impacts texture. Letting milk curdle very slowly via culturing means curds are softer. “It has a completely different mouthfeel, like a cross between eating curds and milk,” Love says. “The texture people think is gross, where it’s like eating cheese gummies—that’s gone.”

So is cottage cheese back? There are signs it might be. Rich Martin, CEO of Green Valley Creamery in Sebastopol, California, says that the company’s decision to release a cottage cheese in 2018 was spurred by demand. In fact, cottage cheese was the most requested product among customers of the lactose-free dairy company.

Martin says it’s all about taste. He compares it to the Brussels sprouts he ate as a kid growing up in the 1970s. Back then, he says, “cottage cheese and Brussels sprouts were two things that my mom ate that I thought were just terrible. They didn’t taste great and there were limited uses. The Brussels sprouts on my plate were all boiled—or steamed, if I got lucky.” Today though, Martin loves Brussels sprouts; roasted, paired with pancetta, sprinkled with cheese. “Now Brussels sprouts taste great because of the way they’re prepared, and I think cottage cheese is the same.”

Maybe it’s the slow culturing, the acidified cream, or the boosted fat content. Perhaps it’s the clean label, flavored mix-ins, or the convenience. One thing is for sure, though, Martin says: “Cottage cheese tastes better than ever.”

Styled by Chantal Lambeth.

Photographed by Nina Gallant.