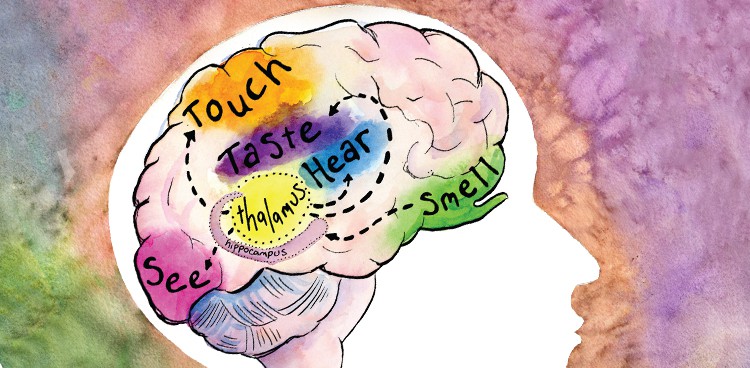

Food. We love it, we savor it, we salivate over glossy photos of it. But how and why, exactly, do we enjoy it so much? When we come face-to-face with chocolate cake, what happens within our bodies and minds that makes us crave a piece? When we take a bite, how do our five senses—sight, smell, touch, taste, and sound—communicate our reaction to our brain? Read on for insights into our profound mind-stomach connections.

Eating With Our Eyes

The first thing we notice about food is the way it looks. The parts of our brain wired to interpret visual information are quite strong—so strong, in fact, that even if other information such as smell or taste conflicts with what we’re seeing, we’ll likely ignore those other senses and trust our sight.

“Humans are better equipped for sight than for smell,” writes Mary Roach in Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal (W.W. Norton & Co., 2013). “We process visual input 10 times faster than olfactory.” Information that comes through our eyes has to travel all the way to the back of our brain before it can be interpreted—yet we still interpret it quickly and prioritize it. The only way that the smell of a perfectly roasted chicken is going to affect you before the sight of its golden-brown skin does is if you’re smelling it from another room.

Because we interpret visual information so much faster than information about smell or taste, the way food looks is important. Even if food smells and tastes perfectly safe, we may avoid it if it looks suspicious. An important takeaway: It’s not a bad idea to spend extra energy on creating Instagram- worthy hors d’oeuvres for your next dinner party. If the taste doesn’t impress guests, the appearance certainly will.

An Evocative Experience

When it comes to food, smell is usually the second sense the brain processes. Smells help us differentiate one food from another, and as anyone who’s had a cold can tell you, lacking a sense of smell can wreak havoc on what we think of as our ability to taste. In fact, 80 to 90 percent of the sensory experience of eating is olfaction, or smelling. There are only five tastes (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami), but hundreds of specific smell molecules.

We tend to think of smelling in terms of sniffing scents that exist outside our bodies, but, in fact, we also smell from within, when food is already in our mouths. Some of the molecules, or “odorants,” that make up scents are brought into the nose when we sniff. Others aren’t discovered until food is in our mouths, at which point these molecules travel to the olfactory bulb, which transmits smell information to our brains.

It’s this internal smelling process that provides much of what we consider flavor. Flavors are created by a combination of our tongue’s tasting one or several of the five basic tastes and our brain’s processing this taste alongside smells that have taken the back road to our nose. Because our mouth warms the food and our tongue and teeth break it down, aromatic gases are set free and become not just more intense but also more complex and interesting than the smells we sniff from the outside.

If smell is so specific, and if the chemicals that are responsible for smells are brought directly into our brains, why is it so difficult for some of us to describe what we’re smelling? Many novice wine drinkers or cheese tasters have this problem. The reason is that smell, unlike other senses, isn’t consciously processed. Instead, the input goes through the emotion and memory center of the brain, the hippocampus. That’s why when you taste smoked cheese, you might remember making s’mores at a campfire.

Food journalist and author Molly Birnbaum lost her sense of smell during a car accident. While she eventually recovered it, she discovered that she had lost the ability to connect smells with their origins. “The biggest problem I had was that I couldn’t really put words to smells anymore,” she says. “I couldn’t recognize them the way I did before the accident.”

While some of the ability to smell is genetic, much of it is simple training. It’s a little known fact: All people can improve their sense of smell and ability to put words to smells if they practice. Birnbaum took advantage of this concept, eventually improving her abilities by training with perfumers.

“The way that I would remember smell was not the way I would remember anything else,” she says. “I had to remember specific smells by images or feelings or memories I would get when I smelled them.”

While matching words to smells might be tough, serving food that will satisfy your schnoz isn’t. Keep in mind that food’s temperature and eventual breakdown (whether by chopping raw ingredients or chewing cooked items) are your friends. Bring cheeses and wines to room temperature to allow release of their smell molecules. And practice those knife skills: The more finely chopped aromatics such as garlic, ginger, or fresh herbs, the more bouquet in each bite, leading to greater appreciation of flavors.

Best Buds

Because the word taste can have a number of different meanings, let’s clarify that here we are referring to the five basics: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. Taste buds, tiny receptors housed within little bumps on the tongue, help us perceive the five tastes. Despite past beliefs that different areas of the tongue were responsible for perceiving different flavors, current research indicates that taste buds discern all five flavors in all areas of the tongue.

While umami—often described as meaty and brothlike—is the least known taste, it’s also the most pleasurable for many people. Researchers at Boston-based America’s Test Kitchen have spent years trying to boost that satisfying flavor in foods. They’ve discovered that the combination of glutamate—the G in MSG and a naturally occurring chemical in many foods—and free nucleotides results in ultimate savory satisfaction.

“A lot of those [glutamate and free nucleotide combinations] are classic pairings, like a beef burger with cheese on top,” says Dan Souza, test cook and senior editor of Cook’s Illustrated magazine. “The beef contains high levels of free nucleotides and the cheese is glutamate-rich. You also find that in Caesar salad, where the parmesan cheese and the anchovies have synergy.”

Different palates favor different tastes (for example, whether we have a sweet tooth or enjoy salt and vinegar chips). Much of this preference is learned through experiences we have as children. In addition, our love for certain flavor combinations is dependent on culture. Sichuan Chinese cuisine, for instance, focuses on bringing all five flavors into perfect balance, while American cooking tends to focus more on just sweet, salty, and umami. Whatever your preference, playing with balance is a fun way to experiment with new pairings or to put fresh spins on old favorites.

Snap, Crackle, Pop

Sound has much more to do with cooking, eating, and drinking than we generally give it credit for. We use audible cues for determining if a pan is up to cooking temperature (listening for a drop of water to sizzle), deciding if food is fresh (the crispy crackle of a potato chip), and even knowing if a drink is hot or cold. In the NOVA ScienceNow special Can I Eat That? (October 2012), host David Pogue was amazed to learn that he could discern the temperature of water being poured, despite being blindfolded. “But how did I know it was hot?” he exclaimed. (Watch the episode and try it; you’ll be surprised at what you know, too.)

When it comes to eating, people have a natural affinity for crispy foods. After all, many fruits and vegetables are at their best when crunchy, exhibiting that they’re “fresh,” Roach says. “They still have nutritional value; they’re not rotten. And that’s something that food people have capitalized on.” From the thin crust of a New York–style pizza to the crusty corner edges of brownies, crispness brings a crave-worthy component to food.

Additionally, sound may add a welcome new element to old standards. During the 2013 Cheesemonger Invitational, for instance, contestant Katie Carter of Arrowine & Cheese shop in Arlington, Va., topped her “perfect bite” cheese pairing with Pop Rocks, the popping candy made with carbon dioxide. This noisy, textural element, sprinkled on Vermont Creamery’s Cremont, topped with lavender seeds and served on a radish slice, helped Carter win third place in the competition.

“The mouth is like a guy who gets bored!” Roach says. “The mouth prefers to have a little surprise, a contrast of textures. For example, putting pistachio nuts or croutons in your salad, or adding mix-ins to yogurt. I think that’s one reason why people reach for crackers when they’re eating cheese.”

For those who are deficient in a sense, texture may take on greater importance, as Birnbaum found after her accident. “When I lost my sense of smell, I relied almost purely on texture,” she says. Temperature was important, too: “If something was hot and cold at the same time, like a warm piece of cake with ice cream on top of it, that was amazing.”

Birnbaum, who chronicled her experience in her book Season to Taste (Ecco, 2011), discovered that Ben & Jerry’s ice cream was a mainstay for folks lacking the ability to smell (likely due to the fact that Ben and Jerry’s co-founder Bennett “Ben” Cohen lacks a sense of smell himself). The ice cream “has textural differences,” Birnbaum says. “They use chunks,” which keep each spoonful exciting.

Whether or not you’re in touch with all five senses, don’t discount the value of texture when creating a meal or pairing. A runny, gooey cheese on a crisp cracker will get you there. And it’s yet another reminder to keep your cheese plates diverse. Eating a variety of creamy and crumbly cheeses, strongly fragrant and mild cheeses, and even differently colored cheeses (blues, anybody?) will ensure that your five senses stay happy and hungry for much, much more.