Best Cheese Region: Vermont

It might have the second-smallest state population in the country, but Vermont wields outsize national influence. From politicians (Bernie) to food entrepreneurs (Ben and Jerry), the rural state attracts and supports out-of-the-box thinkers and self-starters who make things happen. At the same time, a close proximity to nature translates into a drive to preserve the pastoral landscape by producing something delicious from its fields and forests.

Vermont’s flourishing artisan cheese community reflects all of these dynamics. It also builds on the region’s deep dairy-farming traditions, which have been threatened by several challenging decades for the fluid milk economy. As they innovate alternative models, crafters of value-added products like cheese benefit from proximity to large cities. When urbanites from New York City and Boston vacation in the Green Mountains, they make connections and build demand back home, says Patrycja Kotowska, category manager for salumi, formaggi, and dairy at Eataly North America. “We all want to move to beautiful Vermont,” she said, only half-joking. “We can have the cheese at least.”

Today the Vermont Cheese Council boasts around 50 cheesemaking members. Some go way back: Crowley Cheese has operated continuously for almost two centuries; Plymouth Artisan Cheese was founded in 1890 by President Calvin Coolidge’s father; and Cabot Creamery, a farmers’ co-op, is approaching its 100th birthday. More recently, innovators like Vermont Creamery and Jasper Hill Farm have made their mark. Award-winning Cabot Clothbound Cheddar, made at Cabot and aged by Jasper Hill, illustrates the mutual support that not only benefits individual makers, but also lifts all boats. “It seems to me there’s a really unique Vermont spirit of cooperation and collaboration,” says Anthea Stolz, executive director of the California Artisan Cheese Guild.

This year, little Vermont once again raked in a wagonful of American Cheese Society Judging and Competition wins. Thirteen cheesemakers—from tiny Cate Hill Orchard to well-established Grafton Village Cheese—brought home three dozen trophies, including Jasper Hill Farm’s one-two punch for Best in Show. “It’s inspiring to see a state with a population smaller than San Francisco consistently take home such top honors,” says Stolz.

Nowhere is this thriving community more delectably on display than at the annual Vermont Cheesemakers Festival, which just celebrated its 10th year. Held at National Historic Landmark Shelburne Farms, a sustainable education nonprofit and another award-winning farmstead cheesemaker, it’s a bucket-list event for cheese lovers. “Vermont is a dream trip,” says John Antonelli, co-owner of Antonelli’s Cheese Shop in Austin, Texas. “The sheer number of cheesemakers is amazing, the quality of their milk, and level of innovation—and that’s before you even meet any of them.”

Best Cheesemakers

Jasper Hill Farm

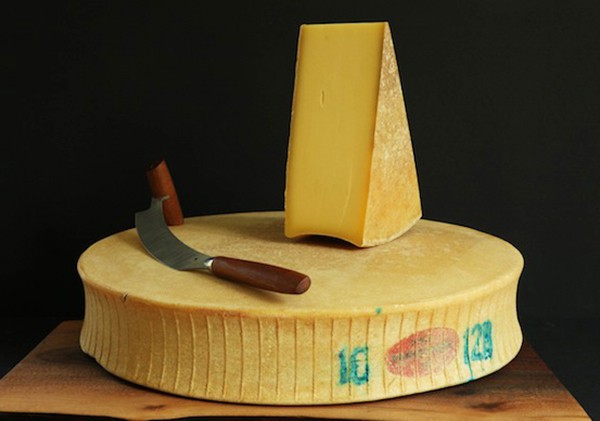

Photo Credit Colin Clark

Mateo Kehler credits Neal’s Yard Dairy in London for the “philosophical taproot” of the farm and affinage company he co-founded with his brother, Andy, 15 years ago. If it hadn’t been for his persistence, however, things might have turned out differently. The brothers were trying to figure out what to do with a defunct dairy farm they had bought in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, and Kehler was trying his hand at cheesemaking. A mentor suggested he further his education through a job with the legendary UK cheesemongers. “The first time I knocked on the door, they turned me down. The next week they turned me down again,” he recalls. “The third week they finally relented.”

At Neal’s Yard, Kehler learned that the founders had “scoured the countryside for the last remaining producer of true Lancashire,” which had been eclipsed by a commodity version. “They saved the last producer of these historic cheeses,” he says. The brothers have a different angle, Kehler explains, but the same motivation to save something historic and valuable. “For us, it’s about conservation of the working landscape through developing cheeses that can support that landscape for generations,” he said.

Their goal is to develop new cheeses that become identified with the region—like in Europe—as opposed to individual makers. “We are trying to create something that’s going to outlast Andy and me,” Kehler says. A breakthrough came when a farmer’s co-op asked for help aging a special batch of cheddar in 2003. That cheese, Cabot Clothbound Cheddar, went on to win the American Cheese Society’s Best in Show just three years later. The ongoing partnership paved the way for the Cellars at Jasper Hill, a 22,000-square-foot cheese-aging facility that cost $3 million. (An early investment came from Neal’s Yard Dairy.)

While centralized affinage caves are traditional in Europe, aging cheeses for others was a new concept here. Despite much attention and acclaim, the road has been bumpy at times. In addition to farmstead cheeses made in-house, Jasper Hill’s 80 employees currently age wheels from five other cheesemakers. The 12 cheeses they market will generate $15 million this year. “It’s like having six wives,” Kehler says, explaining that each relationship, including their own cheesemaking operation, requires careful tending.

Since a few years ago, Jasper Hill has refocused on forging new partnerships within a 15-mile radius of their location. They’ve also been investing significantly in feed technology in order to ensure the safety and quality of raw milk. “Our goal is to benefit this community,” Kehler says. “Cheesemaking is just a vehicle to impact the place we live.”

Photo credit Bob Montgomery

Harbison

Jasper Hill Farm

Greensboro Bend, Vt.

Mateo Kehler, Jasper Hill Farm’s co-owner, begs people not to cut into this lush, bloomy-rind cheese made with the milk of the farm’s Ayrshire herd. Ripened for about three months, its rich paste is prevented from becoming a seductive cheese puddle only by a circular girdle of inner bark hand-harvested from spruce trees in the farm’s woodlands. Instead, he urges you to dip or spoon the cheese—lightly resinous with clotted cream sweetness and a whisper of cauliflower—onto crackers, tart apple slices, or radishes.

St Albans from Vermont Creamery

Vermont Creamery

In 1984, Bob Reese, then the state of Vermont’s agriculture marketing director, was desperately seeking a locally made, French-style goat cheese requested by a chef for an official dinner. Back then, local cheese was pretty much synonymous with cheddar, and most Vermont farmers thought that milking anything but cows was a joke. Enter a dairy lab technician named Allison Hooper, who had apprenticed in France and then married into the state’s only licensed goat dairy. Her fresh, creamy cheese was the hit of the meal—and so Vermont Creamery (originally called Vermont Butter & Cheese) was born.

From that 10-pound batch and initial $2,400 investment, Vermont Creamery has grown to 100-plus employees at its Websterville headquarters. They produce close to 5 million pounds annually of fresh and aged goat’s and cow’s milk cheeses, along with other European-style dairy products like cultured butter and crème fraîche. In 2017, after much due diligence, Hooper and Reese sold the business to Minnesota-based farmer’s cooperative Land O’Lakes for an undisclosed amount.

The pair had been at it for 30-plus years, not only building their own company and the American appreciation of traditional French dairy products, but supporting local and regional dairy farmers and playing a leadership role in Vermont’s growing cheesemaking sector. They were ready to step back. The time was right for investment that could “take our improbably successful family business to the next level,” says Hooper.

The co-founders stay connected. Matt Reese, who worked alongside his father, is now director of finance. One of Hooper’s sons, Miles, operates a goat dairy with his wife that supplies milk to the creamery. And both have immense faith in Adeline Druart, the president at Vermont Creamery’s helm, who is a unique blend of transplant and homegrown.

Fifteen years ago, the microbiology and dairy science master’s student arrived from her native France as an intern. Druart had searched the internet for “fromage USA” and “crème fraîche USA.” “I couldn’t speak the language,” she admits with a chuckle, “but I figured at least I could pronounce the product names.” Druart did not plan to stay long-term, but as a young woman she would never have had the same opportunities in the codified world of French cheese, she explains.

The sale has enabled ambitious new product lines, a significant plant expansion, and long-term commitments to regional milk supply partners. “People are worried when you get bigger,” Druart acknowledged, “but we will still do things the slow way.”

Photo Credit Mark Ferri Photography

1916

Vermont Creamery / Wegmans Food Markets

Websterville, Vt. / Rochester, N.Y.

Vermont Creamery partnered with Wegmans to create a slim, aged goat cheese that is shipped green to the retailer’s state-of-the-art 12,300-square-foot aging facility. Sprinkled with vegetable ash in the cave, it is named and imprinted with “1916” in honor of the founding year of the family-owned grocery business. The small, flat disk was designed to ensure each bite includes both silky rind and velvety paste, and every mouthful a nutty, yeasty, tangy-sweet evocation of French market classics.

Ashbrook from Spring Brook Farm

Spring Brook Farm

For a dairy its size, Spring Brook Farm has a large workforce. The core team consists of 10 full-time employees who care for the farm’s milking herd of 42 Jersey cows and make its Tarentaise, Reading, and Ashbrook cheeses. But they’re also joined over the course of each year by around 1,000 young assistants, who help feed the calves, muck out the barnyard, assist with milking, and—with clean boots and rubber gloves—even carefully turn and wash the champion cheeses.

These youngsters travel mostly from urban schools around the Northeast for hands-on, minds-on weeks thanks to the Farms for City Kids Foundation. The nonprofit is now supported in part by the decade-old cheese operation, but predates it by 15 years. It was established by Karli and Jim Hagedorn, who bought the original 640-acre former dairy farm in 1992. Jim is chairman and CEO of ScottsMiracle-Gro Company, the lawn- and garden-care giant—although the farm and dairy have nothing to do with that business.

Cheese program director Jeremy Stephenson has been involved since the Hagedorns concluded that shipping fluid milk was a waste of time and effort. Rather than create a new cheese, however, they set up a consulting and licensing deal with a successful neighboring farmstead cheesemaker. John and Janine Putnam of Thistle Hill Farm could not keep up with national demand for their own Tarentaise, a recipe they had developed based on cheeses from the Savoie region of the French Alps. The licensing agreement continues, although the recipe and method have naturally evolved to become more specific to Spring Brook Farm.

The much-decorated Tarentaise “is a tribute to the quality of the milk,” Stephenson says. The herd grazes seasonally, and all the dry hay fed to cows during winter is produced on the farm. For minimal agitation, the milk is gravity-fed to the vats. And when it comes to individual prizewinning wheels, Stephenson counsels his team not to place emphasis on which cheesemaker might be responsible. “There is no hero, just a bunch of people working together with animals,” he says. “I tell them, ‘This is a triumph of cooperation. I want you to walk across to the dairy barn and thank the cows.’”

Spring Brook Farm Taerentaise

Tarentaise

Spring Brook Farm

Reading, Vt.

A Vermont farmstead cheese modeled on Abondance and Beaufort of the Tarentaise Valley in the French Alps, these semi-hard, washed-rind, concave-edged, golden wheels are made with the raw milk of Jersey cows fed mostly on grass and dry hay. Aged at least nine months, notes of caramel, pineapple, and umami heighten as it matures. A tiny portion of particularly well-balanced wheels are selected to become Reserve, aged 18 months or more, shot through with crystals and a hint of wood-roasted chestnuts.

Other Best Cheeses

Slyboro

Consider Bardwell

West Pawlet, Vt.

This raw-milk farmstead cheese is made seasonally following the natural kidding cycle of a mixed goat herd, which grazes rotationally to the benefit of both land and animals. Over 60 days, cheeses are washed three times weekly until they become squat, wrinkled hassocks upholstered with orange rind. Although originally washed with Slyboro hard cider, as the cheeses aged beside a different washed-rind, cave microflora became muddled; cheesemakers streamlined to a single brine. The revised Slyboro ages beautifully to develop a creamy outer edge with a soft but lightly granular interior, its acidity balanced by caramelized onion and roasted-apple flavors.

Louis D’Or, Reverie (bottom). Photo Credit Mark Ferri Photography

Reverie

Parish Hill Creamery

Westminster West, Vt.

Based on an Italian-style toma, Reverie owes its distinction to milk from a small herd of Holsteins and Jerseys that are part of the educational program at a high school near Peter Dixon’s creamery. The raw milk is lightly heated and inoculated with only native cultures, while the brine uses solar-evaporated, hand-harvested Maine sea salt. Aged at least five months, the 15-pound wheels become exceptional at a year as they develop a rough, burnished, bronze rind. More mature cheeses offer a buttery yellow paste speckled with tiny holes and crystals, tasting of late-fall hay, toasted nuts, and wheatberries with a hint of butterscotch.

6-Month Cheddar

Shelburne Farms

Shelburne, Vt.

It’s a challenge to make an everyday cheddar that stands out, but the 6-month from Shelburne Farms delivers. The strong foundation is raw milk of the Brown Swiss herd that grazes over the spectacular historic property. The texture is supple with some natural breaks still visible between curd layers. Taste freshly mown grass and just-churned butter with a pleasant foreshadowing of the backbone it would develop if matured. It is like a promising and engagingly precocious youngster who will grow up to be an outstanding adult—but who you enjoy very much right now.

I just regret you did not mention Vermont Shepherd sheep cheese who are a land mark of Vermont. Sold out, year after year winner of ACS Best of show in 1993 and best farmhouse cheese. Thanks David Major and family to produce such excellent cheeses.

Hi Denis,

Our Best Cheese features focus on first place winners each year. Unfortunately, that means we can’t focus on all the delicious cheeses out there! We’ll definitely keep the Vermont Shepherd sheep cheese in mind for future articles. Thank you for commenting!