Welcome to Forbidden Fromage, a series exploring cheesy taboos and prohibitions. Intern Johnisha Levi will look at everything from navigating kosher restrictions and hip hop MCs’ use of cheese and dairy as metaphors for illicit profit and sex to the paleo diet’s dairy prohibition. You’ll get a little history, religion, pop culture, science, and medicine along the way, as we cover thousands of years in the blink of some blog posts.

As the daughter of a World War II vet, I grew up with my dad’s stories of what it was like to be stationed in the South Pacific as a radioman. So naturally, when I had the idea for this blog series, one of the first topics that came to mind was a look at rationing during WWII and what this would mean for cheese consumption during those lean and challenging years fraught with peril and uncertainty.

I’ll begin with the US home front and then move on to look at Britain’s rationing approach.

Rationing in the U.S.

Although my discussion of rationing and wartime shortages is focused on World War II, the country’s approach to food conservation during the World War I provides some important context to the mandatory dietary regulations that were instituted in the 1940s.

Although both World Wars had a huge impact on the diets of everyday Americans, an important distinction is that the U.S. Food Administration relied on the voluntary compliance of the citizenry during World War I. The Administration (headed by Herbert Hoover) and its network of local food boards appealed to the patriotism of Americans to inspire them to cut back on vital foodstuffs. Slogans such as “Food Will Win the War” were employed as a rallying cry to get families on board with eating more fresh fruit and vegetables (as these perishables could not be shipped overseas) and forgoing meat and wheat during “Meatless Tuesdays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays.” In books such as C. Houston and Alberta M. Goudiss’s Foods that Will Win the War and How to Cook Them (1918), the couple urges American civilians to forgo meat by substituting alternative protein sources. Cheese was one of the foods touted as an acceptable protein substitute for meat.

As the Goudisses write:

“Millions of men are on the fighting line doing hard physical labor, and require a larger food allowance than when they were civilians. To meet the demand for meat and to save their grains, our Allies have been compelled to kill upward of thirty-three million head of their stock animals, and they have thus stifled their animal production. This was burning the candle at both ends, and they now face increased demand handicapped by decreased production.

America must fill the breach. The way out of this serious situation is first to reduce meat consumption to the amount really needed and then to learn to use other foods that will supply the food element which is found in meat. This element is called protein, and we depend upon it to build and repair body tissues.”

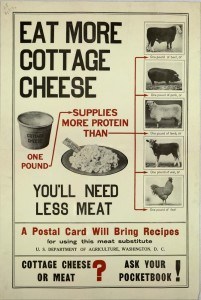

The Goudiss book then goes on to catalog the wide world of protein alternatives, which includes milk, skim milk, cheese, cream cheese, and cottage cheese. For the latter, this clever poster was even made up:

Given the time period, of course, the book recommends the woman of the house to take special pains to “train[] the palate to accept new food preparations.” The Goudisses devote an entire chapter to cheese as a meat substitute, offering recipes that employ soft and hard cheeses like Welsh rarebit, macaroni and cheese, cottage cheese molds, and fondues.

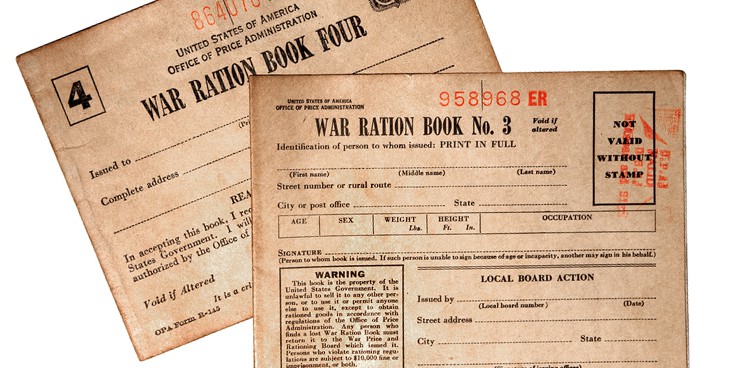

Flash forward to the 1940s, and Americans—even more hooked on cheese—find themselves in the clutches of yet another international conflict. This time, voluntary efforts weren’t going to do the trick. The FDR administration’s Office of Price Administration issued War Ration Book Number One in 1942 for purposes of rationing the country’s sugar supply. Food rations would remain in place until November 1945. As The World War II Museum notes,

“Food was in short supply for a variety of reasons: much of the processed and canned foods was reserved for shipping overseas to our military and our Allies; transportation of fresh foods was limited due to gasoline and tire rationing and the priority of transporting soldiers and war supplies instead of food; imported foods, like coffee and sugar, was limited due to restrictions on importing.”

Ration books therefore became an instrumental part of the home front war effort. In order to buy a rationed good, you had to present the appropriate stamp along with payment. Different colored stamps were employed for different categories of foods: Blue stamps were for canned, bottled, and dried foods, while red stamps got you meats, fats, and cheeses. Ration Books 2, 3, and 4 each contained a total of 64 red stamps, which allotted 2 pounds of meat and 4 ounces of cheese per person per week.

Because hard cheeses like Swiss, gouda, cheddar, and münster were better able to withstand shipping than their soft counterparts, they were the first to be rationed in March 1943, but by June it was announced that Neufchâtel, Camembert, brie, and blue cheeses would no longer be freely available in order to “conserve indicated short supplies of milk.” However, an exemption was made for cottage, baker’s, and pot cheese.

Rationing in Britain

If Americans thought that things were culinarily grim, across the pond in Britain things were much more dire. Due to Britain’s earlier entry into the War, rationing of foods began in January 1940 with butter. Cheese quickly followed on its heels. As in the U.S., similarly guilt-capitalizing slogans such as “Food wasted is another ship lost” were generated to assuage the hunger pangs of the citizenry. An adult was limited to a mere 2 ounces of cheese (as compared to double that in the US), 2 ounces of butter, and 3 pints of milk per week. The cheese was joyless “utility cheese,” and the milk was equally abysmal powdered skim. As Kate Colquhoon, author of Taste: The Story of Britain Through its Cooking, sums it up, “With an all but meatless, fatless, fruitless, cheeseless larder and limited fuel, no matter how inventive the cook, meals were bound to be monotonous, dull, and often beastly.”

When the government realized that the well-off would try to escape the rationing-imposed deprivations, it imposed a 5 shilling-cap on meal costs, and by requiring that restaurants only serve a single course containing one of the following: meat, eggs, cheese, or fish. Some of the recipes popularized in cookbooks like Hard Time Cookery (1940) and the BBC’s Kitchen Front included such “delicacies” as tripe with cheese, and mock crab made with dried eggs, margarine, cheese, salad cream, and vinegar (yeah, I’m unhappy just reading about this).

Rationing continued way past the end of the war in Britain. The cheese industry was all but destroyed, as many cheeses unique to Britain disappeared in the interval, elbowed out by the production of “Government Cheddar.” It wasn’t until 1954—the year following Queen Elizabeth’s coronation—that cheese, butter, margarine, and cooking fats were finally de-rationed.

So now that you’ve learned about cheese hardship during times of War, stay tuned next week for some stimulatingly appetizing discussion of maggots and mites and cheese, oh my!

Feature Photo Credit: “Two food and commodity rations books from World War 2” by Russell Shively | Shutterstock