Welcome to the future: 3-D printers now produce pizza for astronauts, hamburgers grow in test tubes, and ice cream glows in the dark. Scientists stick foods into a big gray machine to turn their vapors into ions and analyze their molecular weights, then feed us chocolate-crusted smoked eel, jasmine-scented liver, and garlic coffee. Indeed, these flavor scientists of the future can pair any ingredient with cheese.

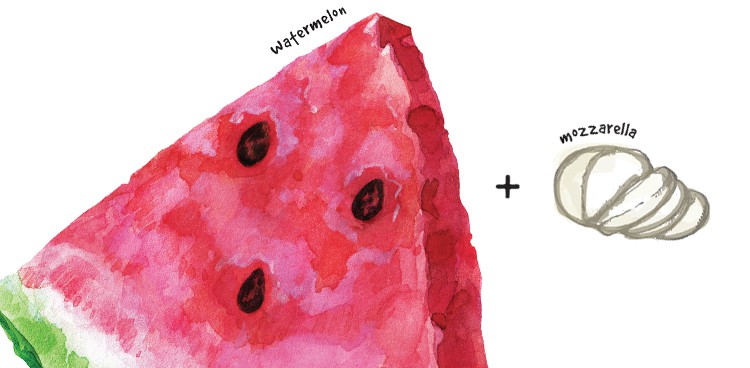

It all calls to mind a Sesame Street song by Monty, the British puppet with the orange face and green nose, which instructs the audience about how to answer the telephone. “Say whatever you please,” he sings, “except for watermelon and cheese.”

I asked Bernard Lahousse, partner and science director at foodpairing.com, if this coupling was as absurd as Monty supposed. Not so. “You have green, fresh, fatty aldehydes in mozzarella linking to the fresh, green aromas in watermelon, and fruity esters such as ethyl butanoate,” Lahousse says.

Most of the pairings we’re familiar with are based on the easily defined texture and taste attributes of the ingredients. Lahousse’s pairings, however, are based on aroma. Aroma refers to the nasal perception of chemicals during inhalation and exhalation (not to be confused with taste, or taste buds’ reactions to sweetness or bitterness).

The ability to perceive aroma is well developed in humans, but it’s based on forces more elusive than taste and texture. According to cheese expert Caroline Boquet, who trains Parisian cheesemongers in the art of pairing, mongers often shy away from suggesting aroma-based pairings. “It appears to them too complex, too scientific, and too new,” she says.

Aroma science is complex because there’s not a “cheese” smell or a “watermelon” smell, but a range of volatile compounds working together. The sheer number of these compounds makes defining a food’s aroma a hefty task: More than 200 have been detected in a single cheddar, for instance. The same compounds are found in almost every food and drink; it’s the amount of each compound in relation to the other compounds present that create a food’s unique aroma profile. While a few dominant compounds may characterize an aroma, others can contribute background notes.

Photo Credit: Le Panda | Shutterstock

In cheese, aroma compounds are created when enzymes found in rennet, starter cultures, milk, and microflora break down milk’s main nonvolatile components (protein, fat, and carbohydrates) into flavorful fragments. Unlimited variables involved in cheese production mean that aroma composition varies endlessly, too.

These days, scientists are working to unravel the complex aroma compounds dominating different cheese styles, many of which may be traced to differences in milk, cheese production, and aging.

For example, blue molds break down certain fatty acids into methyl ketones, which give blue cheese its characteristic fruity, peppery aroma. Copper cauldrons used in the production of Parmigiano Reggiano and many Alpine cheeses “damage” milk fats, liberating fatty acids that are separated further to create esters and lactones, which lend the cheese aromas of pineapple and coconut. Cheeses aged in pine boxes or on pine shelves, or produced from pasture-grazed animals’ milk, develop more flowery, hoppy terpenes. The greater abundance of native flora in raw milk results in more varied enzymes, leading to greater diversity of aroma in raw milk cheeses. Thanks to the continued work of microbes during cheese aging, mature cheeses exhibit more diverse aromas than fresh cheeses.

To pair cheeses based on aroma, the idea is to find beverages or other ingredients that share significant proportions of the same compounds. This theory of compatibility is based on a hypothesis proposed in the early 1990s by chefs Heston Blumenthal and Francois Benzi.

Using a machine that turns an ingredient’s vapor into ions and analyzes their molecular weights (a process known as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry), researchers have been recording aroma compounds found in different foods into databases and creating graphs from the results. Chefs and bartenders are increasingly using these charts in the development of innovative recipes.

Photo Credit: Monash & Anastasia Nio | Shutterstock

Today, Lahousse is on a mission to make aroma-based pairing accessible to all. On his website foodpairing.com, consumers may search by ingredient to find others with similar aroma profiles and scout recipes that combine well-paired groups. Popular cheese pairings suggested by the charts include blue cheese with peach and tomato (they share fruity aroma compounds); mozzarella with almond, dried ham, and fig jam (they share almond aroma compounds), and Gruyère with white chocolate and orange (they share nutty and roasted aroma compounds).

Ultra-modern methods of aroma detection may be changing the way we see ingredients, but some scientists have challenged the idea that similarity equals compatibility. A recent study by Indiana University data analyst Yong-Yeol Ahn and colleagues compared the presence of shared aroma compounds in recipes from Western versus East Asian countries.

Interestingly, Ahn’s team found that recipes from Western countries generally had more ingredients with shared aroma compounds, while East Asian recipes actually avoided compound-sharing ingredients. This suggests that the appreciation of pairings based on similar aroma profiles may be influenced by culture.

Lahousse also cautions that pairing success is influenced by a person’s physiology and experience. “More than 50 percent of our eating experience is determined by factors outside of the food itself,” he says. “We don’t taste what there is, but what we make of it.”

So there’s still something to be said for individual experimentation; whether our food is test tube–grown or 3-D printed, the best place to try it is at our own table, with each of us deciding for ourselves what tastes good. Along the way, tools that suggest innovative pairings can inspire us—these advancements in aroma science are a good reminder to always keep an open mind when trying new things.

Feature PHoto Credit: artsandra | Shutterstock