Photographed by Mallory Scyphers

A teenage boy donned in rubber boots and a white apron walks in and taps his father on the shoulder. In a hushed voice he asks a question in French. The father laughs and answers him, smiling as the boy exits. “He just asked if the cows should come in from pasture because it’s starting to rain,” Nicolas Jotterand, a fifth generation Holstein cow farmer explains. This vignette is a small example of why Le Gruyère AOP is not just any Swiss cheese. The farmers who raise the cows that will be milked for production truly care about their animals’ well-being. Of course those cows won’t stand in the rain; they’ll be herded into a large barn with ample room for resting and ruminating. It’s how it’s done.

Le Gruyère AOP is exclusively produced in an area reminiscent of a certain sing-along movie showcasing an Austrian nun bellowing about hills and joyfully skipping down a mountain. It’s almost unbelievable how magical this place is. A country known for neutrality, chocolate, and watches, Switzerland is also home to 11 other AOP styles of Swiss cheese—not just the slices dotted with holes (Emmentaler).

It can be tricky to untangle the nuances of what makes each Alpine style cheese different from their counterparts. As a cheese magazine devoted to uplifting hardworking makers and their cheeses, this is a question we’re often asked: “What’s really the difference between Gruyère and [insert similar Alpine style cheese here]??” And honestly, my answer (besides terroir, obviously) is… the people. It’s the folks behind the scenes milking, making, aging, quality checking, loading, distributing, importing, etc. etc. etc.

Think about the French Impressionists: Monet, Degas, Renoir, Manet, among many others. Their work is similar, but their unique style distinguishes their work. And so, in this way, cheesemaking is an art defined by who is producing it.

It’s the people.

The Dairy Farmer

Nicolas Jotterand is a Master Breeder of Holstein cows in Biere, Switzerland, a canton of Vaud, who works hard to maintain a family tradition of exclusively providing quality raw milk to the makers who will produce Le Gruyère AOP. And like many farmers, his teenage son is planning to follow in his footsteps. Nicolas is passionate about his craft, proudly displaying a splash of prize ribbons and awards in the relaxed gathering space just above a stable where cows munch on grass and grain. His ladies (the cows) have won dozens upon dozens of accolades over the years. Jotterand is also vice president of Holstein Switzerland, an organization devoted to taking care of Holstein breeders and farmers that’s been around for over 125 years.

As Jotterand explains the ins and outs of his operation, the group I’m touring with oohs and aahs over a just-born calf snuggled near her mother in a nearby enclosure. He opens the gate and lets us pet her. The mother nervously watches as Jotterand tells us the calf will be separated from her mom later that day after colostrum has waned and the calf is steadily walking. Then, he leads us over to a huge pit of manure that’s been mixed into a mud pie-like slurry. This resourceful method of reserving waste will keep him from using chemicals when fertilizing the fields these cows graze. As the tour passes back through the barn, Jotterand heartily pats the sole bull in the first stall, and stops to explain the process of insemination.

These are the steps in the life of dairy farming from birth to earth.

There can be a few challenges for farmers in Switzerland. Zoning laws ensure only specific spaces are farmed—meaning, you can’t just move to Switzerland, buy a chunk of land, and start farming. Also, government subsidies are only given to farmers who meet specific quality and environmental standards. Plus, labor laws are stringent and wages are relatively high. And when it comes to the world of Le Gruyère AOP, there are also specific regulations for farmers:

- Cows must be raised in the specific AOP regions of Fribourg, Vaud, Neuchâtel, Jura, and parts of Berne.

- Cows must graze in alpine meadows or approved pastures in the AOP region.

- Cows must be fed primarily fresh grass during summer and hay during winter. The use of silage is strictly prohibited.

- Raw milk must be processed within 18 hours of milking.

- Strict hygiene practices are enforced.

- Milk must be kept at specific temperatures, ideally between 10°C to 12°C, to maintain microbial integrity.

- Milk must be natural, with no artificial additives, colorings, or preservatives.

- Cows must be raised according to Swiss animal welfare laws, which include provisions for humane treatment, adequate space, and proper veterinary care.

- Dairy farmers are required to monitor the fat-protein content to ensure proper curd formation in cheesemaking.

- Cows must be milked twice daily, and milk must be delivered to makers within 12.4 miles of the farm.

The Maker

Nicolas Schmoutz, a master cheesemaker clad in all white and proudly wearing a stout hat emblazoned with Le Gruyère AOP across the brim, welcomes our group with a broad smile. He speaks with his hands as he guides us through the facility, gracefully meandering between vats and machinery in his make room with a strong sense of purpose. The movements in this space are methodical, yet mesmerizingly lyrical, despite a consistent loud humming and occasional metal clang. Schmoutz is the boss at Mézières Dairy in Glâne, Switzerland, a district in the canton of Fribourg, overseeing all aspects of Le Gruyère AOP production.

Thirty-eight milk producers deliver around 5.7 million liters of milk to this dairy at sunrise and sunset. The make process is simple: raw milk is heated in a copper vat, curds are formed by adding cultures and rennet, then curds are cut to a grainy texture and molded into wheels lined with Le Gruyère AOP branding on the rind and marked with a number and name of the cheese dairy, then wheels are pressed. The next day, these wheels are submerged in a salt bath for 24 hours, then placed on spruce planks and aged for three months at the dairy. After this initial aging, the wheels are transferred to an affineur off-site who will carry out the aging process.

After our tour, in a conference room and kitchen with large glass-paneled windows to spy on the make room below, Schmoutz offers our group a Le Gruyère AOP vertical tasting showcasing a variety of ages, along with a crisp white wine to balance our palates. The younger version, aged between six and nine months, is slightly nutty and sweet, smooth and elastic when bent, and smells of floral grass. As I taste my way through each age, I notice these cheeses increasingly taking on more earthy, savory flavor notes in addition to maintaining a sweet profile, and the textures become more dense and crumbly.

Schmoutz’s wife (and also the boss), Karla Nunes, pops in to say hello, and a fellow cheesemaker just off the floor offers to make espressos. There’s a distinct and lingering aroma of coffee beans mixed with just-soured milk in the air, and everyone is wistfully smiling.

The (Alpage) Maker

The air is damp and chilly and the scenery is a cascade of deep green grass and foggy trees as our bus winds its way up a steep mountain. We arrive at what seems to be the road’s end (it’s not) and unfurl from the van into a wooden cottage warmed by an open fire. That open fire heats raw milk that will soon become Le Gruyère AOP Alpage.

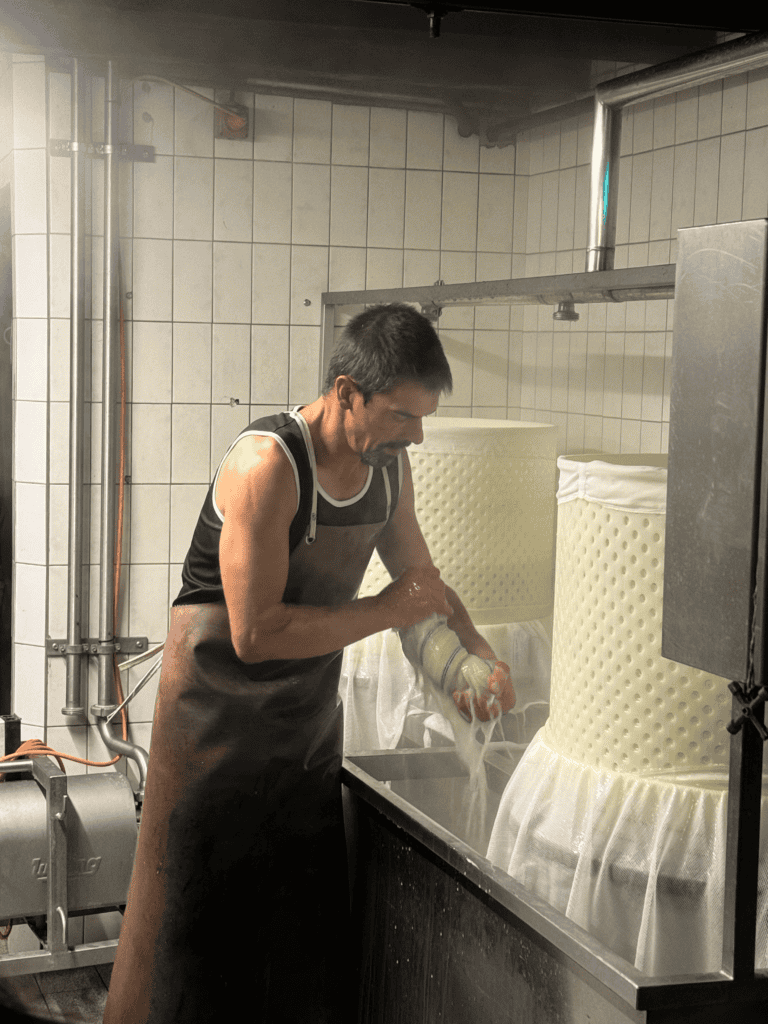

Martial Rod, the cheesemaker at Alpage de la Moesettaz in Le Brassus, is already working, and he’s likely been awake and at it for many, many hours. Like Jotterand, Rod’s son (albeit taller and older than Jotterand’s boy) is helping his dad. We are standing in the make room. Adjacent is the family’s kitchen. Upstairs is the rest of their home. The cows graze in pastures just down the road. This is Alpage cheesemaking, where makers who live in mountain chalets produce small, handcrafted batches of Le Gruyère AOP Alpage during summer months.

You may have heard of transhumance, the communal practice of moving cows from lowlands to higher elevations at the beginning of summer so animals can graze on fresh and floral mountain grass. Alpage makers produce cheese with summer milk to impart a distinct taste of terroir. It’s a practice deeply ingrained in Swiss culture, and one that marks this style of Le Gruyère AOP as unique.

Rod drains grainy curds from a copper vat and pours them into molds just feet from the fire that heated the milk. Notably, this is quite a small make room—nothing like the network of rooms we previously toured with large machines and a dozen workers. However, the make process is similar: raw milk, cultures and rennet, cutting curd, molding (with “Alpage” added to the Le Gruyère branding), pressing (this time with cloth inside the mold), stamping, salting, and aging. But, there’s only one (in this case two) craftsman, and the process is reliant on the conditions of the mountains. Wheels aren’t as uniform as the more industrial facility, though they’re mighty close in size. And a black and gray-mottled farm dog flits about during each step, eagerly nuzzling hands for pets, happily accepting any attention.

Like Schmoutz, Rod offers a tasting of cheeses. Because of the seasonality of Alpage-making, he’s able to experiment with making other cheeses too, and is able to sell his wheels to nearby shops and restaurants. We taste Le Gruyère Alpage AOP, along with a fresh-and-mild farmers style cheese made just a few days prior. The room smells like campfire, the son is showing us videos of cows covered in floral headdresses with large bells dangling on their necks marching in tandem up a steep cobblestone slope, and we are warm with appreciation of the cheese magic happening around us.

The group wanders outside. Lining the chalet are rows and rows of cow bells, each representing either a specific cow from the Alpage de la Moesettaz herd, or a significant event in the family’s lives: births, awards, moments. There’s a herd of cows grazing on the hills in the distance and the music from their bells echoes across the mountain.

The Affineur

Jean-Charles Michaud is a Master Cheesemaker at Mifroma’s caves in the village of Ursy. Like Jotterand, Schmoutz, and Rod, Michaud oozes with pride when he speaks of Le Gruyère AOP and his part in making this special cheese. Our group slips into clog style rubber shoes, long white lab coats, hair nets (and beard nets for some), and descends deep into a vast sandstone cave housing what seems like endless rows of cheese.

The air is ammoniated, similar to that same sour-milk scent of the make room. And it’s cold. This former military bunker can house nearly 140,000 wheels of Le Gruyère AOP, and the cave’s ideal environment controls humidity (95 and 96 percent) and temperature (between 53.6 and 57.2 degrees Fahrenheit ) which makes for an ideal cheese-aging environment.

Michaud’s job is to ensure Le Gruyère AOP is aged in accordance with centuries-old tradition. Wheels are inspected using all five senses:

- Sound: A small hammer is used to lightly tap across the surface of the wheel. Affineurs are carefully listening for any defects that may have occurred during aging.

- Sight: The color of the rind and paste must be visually consistent with Le Gruyère AOP standards.

- Touch: Depending on the age of the wheel, consistency in texture is key.

- Smell: Lactic, floral, toasted, spicy, vegetable, or animal may be present, depending on the age of the wheel.

- Taste: Bitter, acidic, sweet, and salty, are notes only an expert affineur can detect that describe the subtle nuances of flavor required for Le Gruyère AOP to pass inspection.

After tapping a wheel with his knuckles, Michaud uses a cheese trier (a corkscrew-type tool that’s plugged into the rind and removes a small sample from the wheel) to pass around bite-sized pieces of Le Gruyère AOP. This is a younger wheel, and the cheese is pliable with a smooth exterior, creamy mouthfeel, and mild, sweet-and-salty flavor.

What makes this experience all the better is looking across the expansive cave at stacked wheels soaring to nearly 28 feet high. Each row is roughly 327 feet long, and there are many, many rows inside the roughly five acres of space within the cave. Magic.

Le Gruyère AOP Stateside

A few years ago, we reported on the naming debacle that continues to punctuate conversations surrounding Le Gruyère AOP. “Gruyère” is a generic name for cheeses with a similar flavor profile to the real deal. Americans view Gruyère as a style, such as cheddar or gouda. At culture, our job is to educate consumers that there is a difference in the world of Gruyère cheeses, and if you’re buying generically labeled “Gruyère,” you’re not getting Le Gruyère AOP—the stuff from the motherland. One of our freelancers who also attended the trip, Pamela Vachon, cheekily dubbed “look for the Le” as a potential tagline, which is certainly an easy way to distinguish these cheeses, and something I’ll repeat from now on. After all, there’s only one Le Gruyère AOP.

And of course, I can’t report on the magical, mystical qualities of Le Gruyère AOP without touching on the versatility of enjoying it. On a board, it’s highly adaptable and pairs well with a variety of accompaniments. Cured meat matches its brothy, umami notes, while fruity preserves and jams highlight the cheese’s sweet profile. Almonds and walnuts will enhance its nutty qualities, and as far as drinks go, dry white and sparkling wines, pilsners, and even gin are solid matches. For recipes, I recommend melting Le Gruyère AOP in a classic fondue, stacking slices on sandwiches, and whisking shreds into creamy sauces for craveable pastas and mac and cheese.

Iconic Le Gruyère AOP carries a rich legacy of craftsmanship. It’s more than just cheese. It’s a testament to Swiss tradition and excellence. With every wheel, a deep connection to the land and, most importantly, its people is preserved.