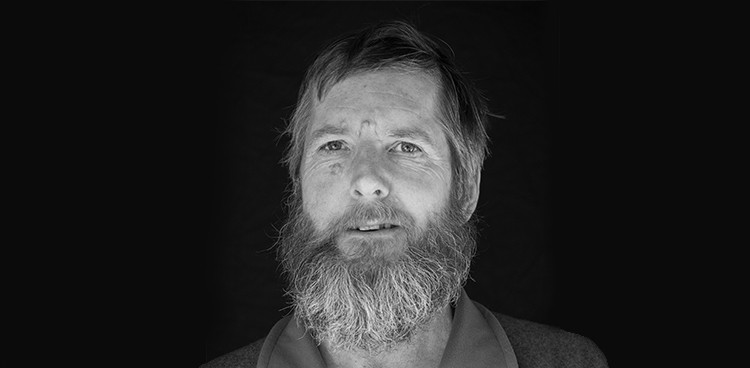

Peter Dixon (left) and Barney moving lactic cheeses into the aging room

Written and photographed by Peter H. Dixon

In November of 2008 I was making cheese at Consider Bardwell Farm, doing some consulting and offering workshops for cheesemakers, when I got a message from Barney Smith, the creamery manager at Ambrosia Foods in Shanghai. It seemed the owner of the company wanted to add cheese to their product line, and Barney thought I was the man for the job. At first, I didn’t believe it. I hadn’t heard much about cheesemaking in China and knew next to nothing about the Chinese dairy industry. Was there even a market for western-style cheeses in China?

There was, and Myra Chan was serious about having this Vermont cheesemaker train her Shanghai staff. During our conversations I learned that Myra had planned to be a doctor, but while waiting for a spot in an American medical school, she took a job at an import-export company in Shanghai. Her talent for logistics and sales led her to start her own company importing European gourmet foods and beverages for the western hotels and cruise ship lines. Dairy products were in demand, as Shanghai—a city of 22 million people—had four million westerners in residence. At the Hyatt Regency Hotel, Chef Christian Rassinoux bought a lot of European cheeses from Myra, and he saw an opportunity if high quality dairy products could be made locally. This was all the encouragement Myra needed, and she hired Barney, a New Zealander working in Frontera’s Shanghai office, to design, outfit, and manage her creamery.

With milk sourced from dairy farms within a 30-minute drive from the creamery, they’d begun producing sour cream and yogurt that year, but Chef Christian wanted cheese and his list was long: mozzarella, pizza mozzarella, provolone, asiago, gouda, havarti, baby swiss, fromage blanc, and of course, French-style bloomy and washed rind cheeses.

It was all possible, but the logistics were complicated, and timing was critical; two aging rooms had to be built, and all the equipment and ingredients had to be in place in advance of my arrival. I designed the aging rooms and Myra’s father, a retired engineer, was enlisted to build them. I was more than a little apprehensive, and since I had seen so many cheesemaking projects get delayed and derailed, I wondered if it would all come together.

It was time to meet face-to-face, and Myra was on board. “We will come to you and make a business agreement,” she said. In early March, Barney, Myra, and her father came to Vermont. Barney attended my cheesemaking workshop, Myra’s dad studied the aging rooms, and we made a deal: I would go to Shanghai for ten days in April. “Everything will be prepared,” Myra promised. I had a feeling she would have everything ready before then.

“We really live in a global village; right here we have an American who came to China to teach a New Zealander to make European cheese for a French chef!”

I arrived at Pudong Airport on March 23. Endless rows of greenhouses appeared as the jet descended through the mist. Springtime in Shanghai means blossoms blooming, leaves bursting from buds, roadside stands with wooden stalls and flatbed trucks full of fruits and vegetables, and everywhere people working in gardens. The roads were full of cars, trucks, taxi cabs, mopeds, scooters, motorcycles, and bicycles. Some motorcycles had been converted into delivery vehicles by attaching racks to their sides and back; the drivers were hardly noticeable, walled off by their towers of freight.

In the morning, Mr. Wang, the even-keeled, bespectacled plant manager, picked me up at my hotel. Next, we collected Barney, who warned me that I was in for quite a ride. The creamery was on the outskirts of the city. Traffic was heavy. The drivers paid little attention to traffic lights—they slowed down as they approached, but the color seemed irrelevant, and games of chicken ensued. Drivers crept into the intersection, daring each other to go, while cyclists and pedestrians vied for any available space. It was kind of crazy—no, it was bonkers. Mr. Wang was clearly a veteran Shanghai driver, “You can see why I don’t drive,” Barney quipped.

When we arrived at the creamery, it was obvious that Myra was very serious. The main processing hall was full of stainless-steel milk processing equipment: all made locally, to spec, and of excellent quality. We climbed the circular, stainless steel staircase to a mezzanine to find the cheese vat, steam kettles, and two small, water-cooled aging rooms. Myra’s dad had done a fine job on the aging rooms, which were insulated, paneled, and cooled by stainless steel serpentines of pipe hanging from the ceiling.

Barney and I made at least two batches of cheese a day for eight days straight, starting at 8 a.m. and not finishing before 7 p.m. Sometimes Mr. Wang joined us, as he would be helping Barney teach the other workers to make the cheeses after I left. Mr. Wang was a careful and thoughtful worker, and an excellent plant manager. The white-uniformed staff looked in on us as they went about their daily chores, making yogurt and Mr. Wang’s creation—skim milk ricotta. The staff had taken easily to making the original product line up, and I didn’t doubt that they would take to the new cheeses we were working on.

One morning I went with Xiao Shen to pick up the milk. The drive to the dairy farm took us well into the country, through a flat green landscape of villages and farms. The airy, modern tie-stall barn housed several hundred Holsteins; like many large dairy operations in the US, the chained animals were fed silage, but from wheelbarrows instead of tractors. Xiào Shen pumped the milk into the tanker, ran the tank cleaning cycle, and we headed back to the creamery where the milk was unloaded and immediately standardized and pasteurized before the day’s cheesemaking got started.

The long days were paying off and the aging rooms filled with cheese. By the end of the week, the bloomy rinds were developing, and we’d made nearly every cheese on the list. I enjoyed the work, and the staff was diligent and kind, taking time to share a cup of green tea during breaks. The team was made up of as many women as men, with people of all ages—young and old alike. Most of the staff ate lunch together at a restaurant a short walk from the Ambrosia warehouse. It was a communal meal—the hot pot, a small cauldron of simmering broth was surrounded by a lazy Susan laden with platters of meat and fresh vegetables that we plucked up with chopsticks and dipped into the steaming broth. I was astounded by the wide variety of tofu: noodles, airy puff balls, flaky squares, puddings, and the firm chunks that I was used to eating at home. “Look Peter! Chinese cheese!” exclaimed Xiào Shen as he picked up a tofu cube with his chopsticks. These lunches with the crew were delicious and always entertaining.

Yet Myra rarely joined us for lunch—she was completely occupied with business. In addition to dairy manufacturing and sales, she managed a large inventory of imported provisions. She had four cell phones and was making deals at all hours. By the end of my trip, I wondered if she slept at all. Nevertheless, Myra was a good boss. She treated everyone with kindness and respect; when Myra spoke, people listened.

On my last night, Myra, Barney, and Chef Christian took me to dinner at an Italian restaurant. The food was almost as good as the conversation—Christian is from the French Alps, and when we discovered we shared a love of mountaineering we regaled the table with stories of our youthful adventures. But mostly we all spoke of food and the global trade network. At one point Barney looked from Myra to Christian to me and said, “We really live in a global village; right here we have an American who came to China to teach a New Zealander to make European cheese for a French chef!”

Shanghai has long been a center of trade and commerce with the west. With over four million foreign residents it wasn’t surprising that there would be an appetite for European-style cheeses made locally. When word got around that Ambrosia was making high quality cheeses, the Hyatt wasn’t the only hotel placing orders. The boulangeries and provisions shops of the old French quarter were also keen on the new product line. Chef Christian had been right—China wanted cheese, and I was glad to help.

As I settled in for the long flight home, reflecting on my time at Ambrosia Fine Foods, pondering my good fortune to have been able to make cheese in China and hoping to be able to return one day.

Editor’s note: Ambrosia Dairy was acquired by Ornua, the parent company of Kerrygold, in early 2016. In an interview with New Food Magazine, then Ornua CEO Kevin Lane said, “Ambrosia Dairy is particularly well known for the quality of its cheeses and it has been at the forefront of the development of the domestic cheese market in Shanghai.”