Three artisans follow wildly different journeys to chase the ever-romantic (and not so easy) road of entering the dairy industry.

I’m sure I’m not the only person who has passionately believed that cheesemaking was once their true calling. I had even planned to move across the country, figure out how to source milk, and tend my own herd of sheep or cows before I reluctantly came to terms with the fact that writing about the irresistible food of the gods is the closest I would ever come to making a wheel. But that is not the case for three cheesemakers who left their respective careers teaching high school French in Maine, practicing law in Chicago and New York, and practicing healthcare in California. For every cheese lover out there, we can all be grateful for these brave career-changers who have successfully taken the leap!

Spring Day Creamery

Durham, Maine—Sarah Spring

Sarah Spring began teaching French to middle school and high school students 38 years ago. But it was almost 20 years ago, while making batches of yogurt in her kitchen in Falmouth, that she began to think about making something more. “My students thought I was a little bit nuts as I was incorporating yogurt making into my curriculum—anything to avoid conjugating,” she laughs.

Spring started reading and learning about cheesemaking as much as she could, and in 2005, she joined the volunteer-led Maine Cheese Guild. At the time, there were only 15 cheesemakers in the entire state; today there are 80. She eagerly joined the close-knit group and “embraced the whole thing.”

While Spring was still teaching, she and her husband Gary moved to an old farmhouse in Durham. Her initial cheesemaking efforts quickly took over the entire house—hanging it from rafters, aging it in the bedroom, and stockpots and water baths were everywhere else.

Eventually, Spring’s husband transformed a dilapidated shed connected to the main house into Spring’s own 8-by-10-foot make room with a draining table. In 2008, she became licensed and produced her first batch of blue cheese. She has since moved her small operation to a garage attached to her kitchen but describes it as still very crowded.

“My husband moves and washes the heavy cans of organic Jersey milk that are delivered to our house on Mondays,” explains Spring, who sells her cheeses a two different nearby farmers’ markets. Spring enthusiastically describes the various styles of cheese she makes (aged blues and soft-ripened), and her sense of humor allows her to embrace the many variables that go along with cheesemaking. She sometimes offers accidental wheels at markets (ones that haven’t gone exactly to plan) and describes blue cheese as the eighth grader of the cheese world—it’s fidgety and just wants to play. When asked if she missed teaching, she says her booth at the market often feels like the United Nations with folks speaking various languages throughout the day. It seems Spring gets to have her cheese and eat it, too.

OroBianco Italian Creamery

Blanco, Texas—Phil Giglio

A bit farther southwest, Phil Giglio, an attorney once based in Chicago and New York, has a herd of 400 water buffalo and makes mozzarella and gelato in the Texas Hill Country.“ We are the first and only water buffalo creamery in the state of Texas,” says Giglio of OroBianco Italian Creamery, where he sells gelato, cheese, and pizza out of his Blanco-based brick-and-mortar store.

Brought up on a farm in upstate New York, Giglio began to recall a visit to Italy and imagine a more agrarian lifestyle that would bring him closer to the land. He settled on making buffalo mozzarella. After reading countless books, the lawyer-turned-rancher purchased a herd of water buffalo in 2018 and learned how to make mozzarella. But it turned out to be much harder than he anticipated. So, Giglio teamed up with a professional cheesemaker who perfected the recipe, and in the process, discovered that it was easy to make delicious gelato with the rich, high-fat milk (and the margins were better, too).

In 2020, Giglio purchased a building that previously housed a dry cleaner and transformed it into a creamery. They weathered COVID by turning their storefront into more than a creamery and sold pizza, wine, cured meats, and other retail items. They also developed relationships with chefs and pizzerias, selling their small batches of mozzarella to hand-picked restaurateurs from around the region and in Austin.

OroBianco currently has three cheeses in their case: Blanco Fresco, Bufaletta, and Bluebonnet. Their production is small so they don’t offer shipping—their cheese can only be purchased in their store. But there are three OroBianco creameries throughout Texas, and according to Giglio, another one is in the works.

While he hasn’t entirely quit his day job, Giglio still spends much of his time in Texas’ Hill Country, managing his operation as it continues to expand. Giglio refers to his products as traditional Italian–influenced cheese hand crafted in Texas—aka Italian inspiration, Texan terroir.

Toluma Farms and Tomales Farmstead Creamery

Tomales, California—Tamara Hicks & David Jablons

Husband-and-wife team Tamara Hicks and David Jablons answered their call to cheese in the early 2000s when both were working full time in healthcare—one as a surgeon and the other as a psychotherapist in San Francisco. “It was a trip to Italy staying on farms and discovering Slow Food (Chelsea Green Publishing Company, 2001) that inspired us and got us thinking about having our own farm,” explains Hicks, who now manages a 160-acre farm with 200 goats and 80 sheep, plus tour offerings, volunteer opportunities, and six-month apprenticeships.

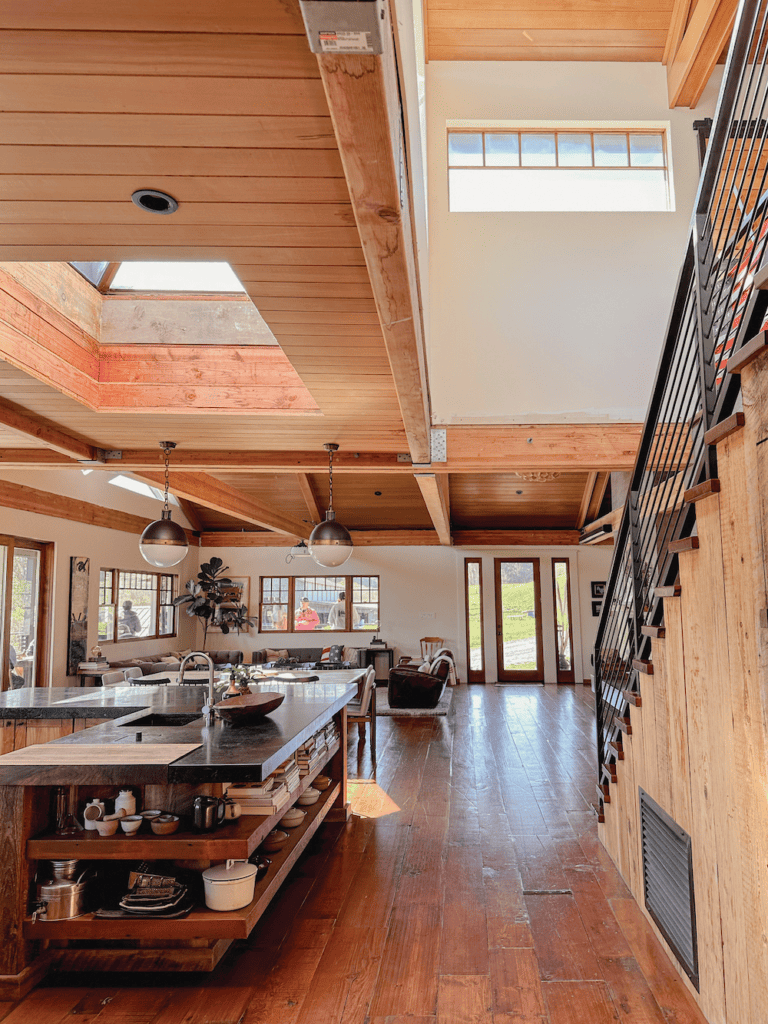

In 2003, Hicks and Jablons purchased a cow dairy just outside the tiny town of Tomales that had operated for 80 years but went into foreclosure and fell into extreme disrepair. The couple spent the first five years cleaning up the property and restoring it to an operational dairy. They transformed a ramshackle house into a communal workspace, built a milking parlor where a chicken coop once stood, and restored multiple structures. Instead of cows, they opted for goats, and in 2013, began producing cheese and selling it at local farmers’ markets.

“It’s important to us to educate buyers that cheese is seasonal,” explains Hicks, who has retracted their distribution. For the last three years, they have almost exclusively focused on selling their six different cheeses at local markets. Hicks also notes that the couples’ values are an integral part of their dairy. “It eventually dawned on me how everything we do is all connected, mental health, social equity—our model has always been to be as inclusive as possible.”

In addition to being an inclusive, value-based dairy, Toluma Farms and Tomales Farmstead Creamery also lets you play dairy farmer for a long weekend. The property boasts a four-bedroom Airbnb, complete with fresh eggs and cheese upon arrival. Try your hand at herding, milking, and making, or roam the vast property on a quiet hike. It’s a getaway that just may kickstart your newfound passion for cheesemaking.

Related:

- Bonnie Shershow’s Perfect Cheese Pairings

- 5 Reasons Industry Pros Should Join Cheese State University

- One Cheesemaker’s Horseback Journey Through Mongolia