Although they tend to stay hidden, blue molds grow all around us. If we magnified forest soils, bales of hay, and forgotten loaves of bread, we might see them: clustered colonies of Penicillium roqueforti. Up close they resemble otherworldly paintbrushes, their long filaments split into branches. And at the end of each branch, rotund, blue-green spores—which give the colonies their characteristic hue—cling on, awaiting a habitat of decaying organic matter to latch onto.

It’s likely that the mold discovered cheese before cheesemakers discovered the mold. Centuries ago, while growing naturally in the soils of the Combalou caves in southern France, P. roqueforti found welcome homes on the wheels of cheese that locals stored in the humid, cool caverns. Once settled onto the wheels, tiny spores transformed into fruiting mycelium colonies that consumed fat, converting it into specific methyl ketone molecules that gave the cheeses a uniquely piquant flavor.

Soon, cheesemakers began capitalizing on the blue mold’s capacity to create unique aromas. They noticed that unlike most molds, this one displayed an ability to grow with just a little oxygen; as a result, it bloomed in the cracks and crevices left in unpressed wheels.

Makers let it colonize loaves of stale bread, which they crumbled into the curd. Instead of growing on the outside of the cheese—a surface that tended to be a little too salty for its taste, anyway—the P. roqueforti flourished within. By the year 1070 that speckled blue wheel—called Roquefort— was already appearing in written Carolingian texts; by the Enlightenment it was being called the “king of cheeses”; in 1925 it became the first protected Appellation d’Origine cheese in France.

Fast-forward over 900 years since Roquefort’s first written mention, and its namesake mold is now cultivated in laboratories. Cheesemakers across the world order packets of its spores directly to their doorsteps. Cheeses with P. roqueforti are widespread, but there’s one thing they tend to have in common: the blue veins that course through their interior paste. For almost a millennia, makers directed the mold to the inside of wheels—until a farmer in central Massachusetts had a crazy idea.

A New Blue

In 1981, Bob Kilmoyer and his wife, Lettie, were teaching themselves how to make cheese. They’d head into their kitchen at Westfield Farm with a gallon of goat’s milk and, using rudimentary equipment, would make six or so Camembert-style disks at a time. Bob didn’t know much about cheesemaking, but he wanted to create something new. So he decided to inoculate some of the milk with P. roqueforti mold spores, then separate those disks from the others to age in a mini cave—a basket covered in plastic wrap poked with holes. The soft-ripened cheese’s dense, melty paste left no oxygen-filled crevices in which the blue mold could flourish; instead, it began creeping up on the surface.

The disk, which the Kilmoyers named Hubbardston Blue after their small Massachusetts town, confronted no shortage of skeptics, among them a Frenchman who visited Westfield Farm and tasted it. His response? Not good.

“He told them that it wasn’t going to work, that the roqueforti could not ripen properly on the surface,” says Bob Stetson, who now runs Westfield Farm alongside his wife, Debby. According to her, that response only amped up Kilmoyer’s determination. “A challenge from a Frenchman,” she says. “He was like, yes I will.”

The Kilmoyers decided to enter Hubbardston Blue into the American Cheese Society (ACS) Judging & Competition—but there, too, the cheese confronted doubters. One year it was discarded when the blue mold was mistaken for unintended spoilage; another year points were deducted because of a lack of blue veins. “It didn’t look like anything anyone had ever seen,” Lettie Kilmoyer told an audience during an ACS conference speech in 1994.

But people were buying it. Encouraged by positive feedback from mongers, the Kilmoyers continued experimenting. They began inoculating creamy fresh chèvre curd with blue mold spores before rolling it into a log shape, making a second cheese called Blue Log and a smaller version called Bluebonnet. To improve consistency in all the blues, they noted when a particularly good strain of P. roqueforti spores arrived from their supplier, preserving it and using it for months.

As buzz about blue rinds began to spread, the American Cheese Society caught on, and created an entirely new contest category: External Blue-Molded/Rinded Cheeses—a game-changer for the Kilmoyers. In 1987, Hubbardston Blue was awarded Best in Show, besting artisanal heavyweights in all other categories from across America. In 1996, Bluebonnet received the same award. Bob Stetson estimates that Westfield Farm’s blues have collectively garnered between 50 and 75 ACS medals since the category was established.

A Balanced Blue

While gaining recognition in the cheese community was one challenge, consumer acceptance has been another. To this day, Debby Stetson still gets calls from panicked customers who are about to serve the cheese, wondering if they should be cutting off its blue fuzz.

Yet despite a jarring appearance reminiscent of forgotten stale bread, externally rinded blues tend to offer subtler flavors than their veined counterparts. “It’s a blue cheese for people who don’t like blue cheeses,” says Dallas-based Mozzarella Company’s Paula Lambert of her Deep Ellum Blue.

Lambert had been making a Taleggio style square, and when it grew blue mold accidentally, customers began asking for squares with the defect. So, she started bathing the cheese in a P. roqueforti solution before aging. When the blue mold is fuzzy enough, she pats it down with some olive oil to control the growth. The result? “It has a faint blue cheese taste, but it’s very smooth,” she says. “If you needled it or put the blue mold in the curds, it would be totally different.”

Sarah Spring, owner of Spring Day Creamery in Durham, Maine, was going for a similar nuance in her externally rinded Déjà Blue. “People who don’t like blue tend to like it,” she says. “There’s no salty veining that’s in-your-face.” A close look at Déjà Blue’s surface reveals blue mold patches tempered by white, cloudlike splotches and zones of gray wrinkles—a mottled mix that tends to characterize many cheeses in the young category.

“Blue mold is known for being communicative with other cheeses,” says Spring, who ages Déjà Blue alongside other styles in a “natural rind” cave. While she doesn’t inoculate milk for Déjà Blue with white Penicillium or Geotrichum molds, they colonize the disks anyway. “I used to be a teacher, and I think of the molds as uncooperative middle schoolers—they all want to fidget and play with each other,” she says.

Likewise, at Mystic Cheese Company in Groton, Conn., cheesemaker Brian Civitello sprays young, stracchino-style squares of cheese with a cocktail of yeasts and bacterias—no blue mold spores included. After two weeks maturing in his shipping pod turned aging cellar, the squares pick up molds from other blue cheeses in the cave, developing splashes of aquamarine fuzz. “We have a tiny ripening room, and such a heavy presence of the P. roqueforti mold that we don’t need to continually inoculate milk,” he says.

All that mold-fidgeting created a challenge for Mike Koch and Pablo Solanet of Firefly Farms in Accident, Md., who first set out to create an externally molded blue pyramid, MountainTop Bleu. The pyramid’s proximity to a Brie-style cheese during aging, however, quickly resulted in cross contamination. P. Roqueforti is a cousin of other Penicillium molds like camemberti and candidum, which create fluffy white rinds; thriving at similar pH and temperature, the molds often grow at once on the same cheese.

Koch and Solanet eventually decided to allow both molds to flourish simultaneously, aiming for a balance. Each day they watch the pyramids change color as colonies battle it out. First the P. roqueforti mold takes hold, but then the candidum starts to cover it. “When it’s young, you can see the blue through the white, and then the white gets snowy and downy and covers the blue,” Koch says. “But then at the end of the ripening, the blue sort of returns.” As mold evolves, flavor changes, too—from lactic and silky with delicate blue notes to robust and mushroomy with a blue piquancy that Koch says “really shines.”

Kathryn Spann of Rougemont, N.C.–based Prodigal Farm compares the evolution of blue mold on the rind of her Bearded Lady—a lactic cheese inoculated with Geotrichum and rubbed with a mix of ash and P. roqueforti —to the growth of a forest. “There’s a succession as the forest grows up,” she says. “First certain plants come in, and then other plants come in, and the trees grow and they shade out the original plants so those can’t grow anymore—that’s analogous to the succession on a rind.”

Sarah Spring also sees the mix of molds growing on her externally rinded blues as a reflection of nature—in this case, the splotchy gray rocks that speckle the islands of nearby Penobscot Bay. Déjà Blue captures their likeness so closely, Spring says, that she sometimes displays it on a platter amongst rocks she’s collected from a local island and challenges customers to pick out the cheese. “It has all of the colors that show up on the beach,” she says.

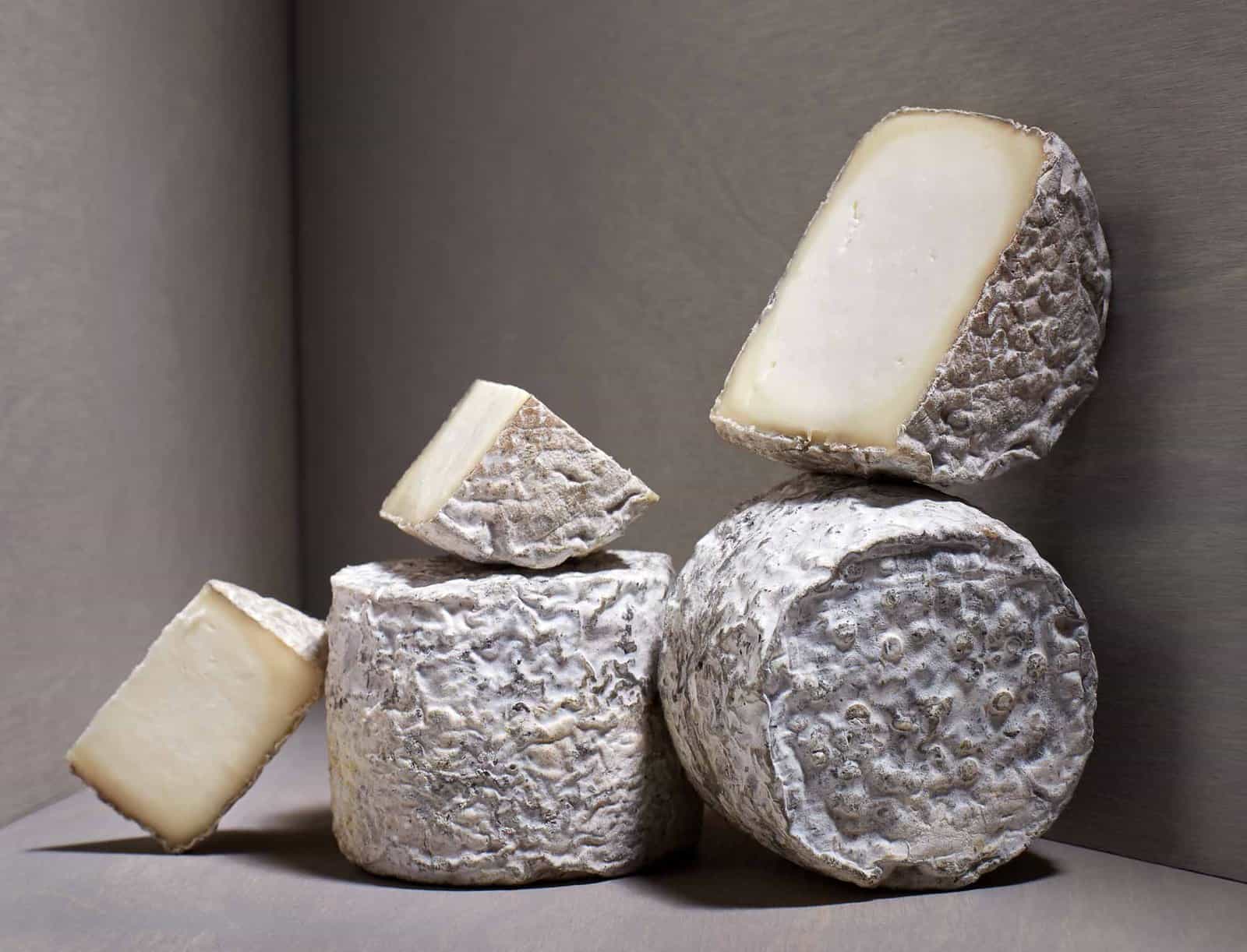

The mottled nature of so many externally rinded blues hints at another trait they share in common: In large part, they’re made by small-scale artisans who are carving out space in a category that remains extremely limited. And because blue molds like P. roqueforti grow naturally in many environments, they’ve likely been colonizing cheese wheels accidentally for hundreds of years, blooming secretly in natural rinds.

In that way, makers like Spring are just giving a natural process a bit of a boost. “Déjà Blue is a reflection of where I live, in an old farmhouse,” says Spring. “I don’t have state-of-the-art anything; I don’t toy with Mother Nature.” According to Stetson, developing an automated production process for externally rinded blues could result in increased consistency in the final product— a more regular balance between different mold strains, for example.

But he doesn’t think the unique style has enough of a market to support an industrial-scale version right now. Instead, he’s satisfied with the small niche Westfield Farm has helped establish for the past few decades. “If people want to buy a blue-veined cheese, they’ve got hundreds to choose from,” he says. But blues that ripen cheese from the outside are more elusive, their raucous, ever-changing surfaces a reminder of the moldy organisms that hide among us.

Tasting Notes

Hubbardston Blue

Westfield Farm in Hubbardston, Mass.

Pasteurized cow’s or goat’s milk

The original externally rinded blue is a dainty disk covered in powdery, blue-gray mold, which imparts complex flavors reminiscent of truffles and mushrooms, with a blue piquancy and lactic tang.

Blue Bonnet

Westfield Farm in Hubbardston, Mass.

Pasteurized goat’s milk

With age, the soft, featherlight core of this one-ounce button is gradually overtaken by an expanding creamline. Flavor yields aromas of lemon and stone, melting into a bitter finish.

Blue Log

Westfield Farm in Hubbardston, Mass.

Pasteurized goat’s milk

A larger-format version of Bluebonnet, Blue Log has more of the whipped fresh chèvre paste reminiscent of lemon cheesecake, and a slightly grassier profile than its diminutive sibling.

Déjà Blue

Spring Day Creamery in Durham, Maine

Pasteurized cow’s milk

We love how this gray, mottled cheese resembles a rock on the beach, while its flavor—briny and savory, with notes of soy sauce and seaweed—reminds us of the ocean.

Monte Enebro

Queserías del Tiétar in Ávila, Spain

Pasteurized goat’s milk

Larger than your average externally rinded blue, this Spanish log clocks in at almost three pounds. On the palate, it starts out mild before intensifying, with notes of buttered popcorn and zesty hits of blue from the pleasantly musty rind.

MountainTop Bleu

Firefly Farms in Accident, Md.

Pasteurized goat’s milk

While the blue is barely detectable in the white rind of this mold-ripened pyramid, its tiny hint of sharpness is a lovely complement to the cheese’s bright flavors of grass and milk.

Bearded Lady

Prodigal Farm in Rougemont, N.C.

Pasteurized goat’s milk

This wrinkly-rind button smells of fresh mushrooms and tastes of vanilla and minerals, with mild yeasty notes and a lemon finish.

Deep Ellum Blue

Mozzarella Company in Dallas, TX

Pasteurized cow’s milk

A scaly, blue-green exterior offers a bold punch at first bite, but the snow-white paste of this dense cheese is mild and creamy.

Sea Change

Mystic Cheese in Groton, Conn.

Pasteurized cow’s milk

The mesmerizing blue-green white rind of Mystic’s square-shaped crescenza style surrounds a gooey, creamy paste that boasts notes of hops and mushroom confit.

Photographed by Nina Gallant

Styled by Chantal Lambeth