Origin

In the days before big agriculture converted much of our country’s arable land to vast swaths of corn and soy, the American dairy cow lived a very different existence. Grain crops were a valuable resource reserved primarily for human consumption, and cattle were obliged to get by on whatever they could forage from the pastures on which they lived.

As a native landrace breed, the Randall cow represents a throwback to these bygone days of agriculture. The term “landrace” refers to a strain of animals or plants that developed naturally in isolation and with minimal interference from humans. Like all other American landrace breeds—most of which have long since vanished—the Randall is an amalgamation of stock imported from Europe by the first settlers.

History

With the advent of modern farming techniques, U.S. farmers across the country were busy “grading up,” converting their herds’ genetics to keep up with the changing times. One man, however, Samuel J. Randall of Sunderland, Vermont, chose not to buy into the new fad. “Mr. Randall liked his cows the way they were and thought a lot of what was going on was foolishness,” explains Phil Lang of Howland Homestead Farm, a breeder in South Kent, Connecticut. And so, as the world of dairy farming changed around him, Mr. Randall and his family kept, bred, and selected their cattle in virtual isolation for over 80 years. Still, by the time Everett Randall passed away in January 1985, the future of the Randall cow was in serious jeopardy.

In Jefferson City, Tennessee, Cynthia Creech read about the plight of this genetically rare breed in the Country Journal. Wanting to save this living piece of American agricultural history, Creech contacted the author of the story and with his help began the difficult process of recovering the 15 remaining specimens of the Randall breed from a farm in Massachusetts. Working with a geneticist from Virginia Tech, Creech helped cultivate the Randall breed back to a healthy population. Now, the Randall numbers are holding steady at around two hundred.

Appearance

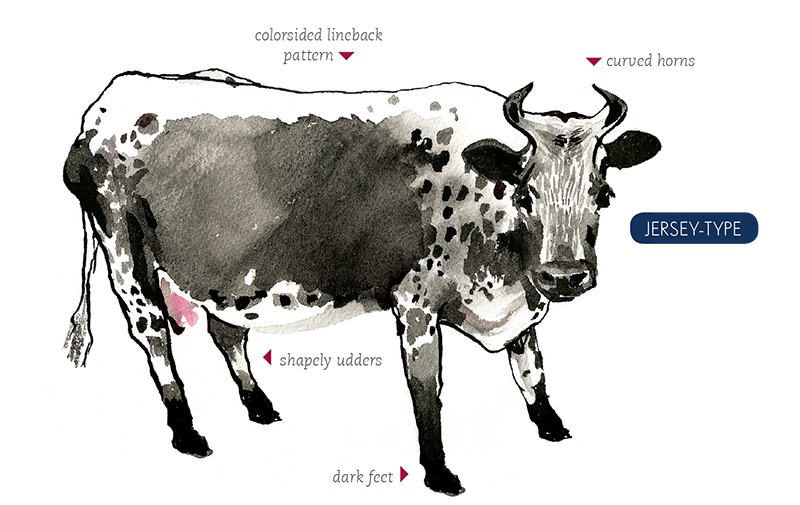

Randall cattle are a medium-size breed with a somewhat primitive conformation. On the whole they tend toward the dairy type, with shapely, well-attached udders and sound feet and legs. Three distinct types appear most frequently: a fine-boned Jersey type with tightly curved horns; a smaller, more dual-purpose variety; and a large, boxy, long-horned type reminiscent of a Holstein.

Most exhibit a striking “colorsided lineback” pattern characterized by a white body with dark sides, muzzles, ears, eye rings, and usually feet. The predominant colors are black or blue-black over white, but as breed numbers grow, new variations such as mahogany, blue, gray, and occasionally recessive red (a color trait known to have existed in Everett Randall’s herd) are beginning to appear.

Temperament

Randalls are able, smart, and tough, and it is this hardy character that makes them an ideal match for the homestead or hobby farmer. “This is a true subsistence-farm-type cow,” explains Lang. “Randalls fit beautifully into the grass-farming paradigm—we’ve been raising them on grass and hay only for 20 years, and they do exceptionally well.”

“They live a very natural existence,” adds Creech. “They will grow fat in the summer and raise healthy calves, grow skinny in the winter, and then come back healthy in the spring ready to do it all again. If you handle them regularly and are very gentle and easygoing, they will become tame, almost doglike,” she says. Lang remarks, “They know how to be a cow so perfectly—they don’t really need our assistance or interference.” Creech adds, “They have a genetic ability to carry on, almost a feral quality; they can carry on as a cow without much human interference.”

Milk & Cheeses

According to Creech, the milking abilities of Randalls are “all over the map,” which, she explains, is typical of animals that have not been single-trait selected. Though not ideal for large-scale operations, it does make them well suited to a small-production farm.

Jim Stampone of Winter Hill Farm in Freeport, Maine, has been making cheese from the milk of his small herd of Randalls for the past 15 years. In the beginning, Stampone experimented with soft cheeses before finally settling on what he feels is the best match for his Randalls’ milk: an aged (8 months) cheddar. “It didn’t really have the flavor I wanted at four months,” says Stampone, “but when I let it go for another four, it suddenly became very sharp and wonderfully flavorful.”

According to Winter Hill’s customers, there is a quality about Randall milk and cheese that they haven’t experienced with dairy products from other breeds. “Even though Randall milk has about the same butterfat as Holstein milk, it tastes much richer,” explains Stampone. “In fact, my customers tell me it’s the only milk their kids will drink!”