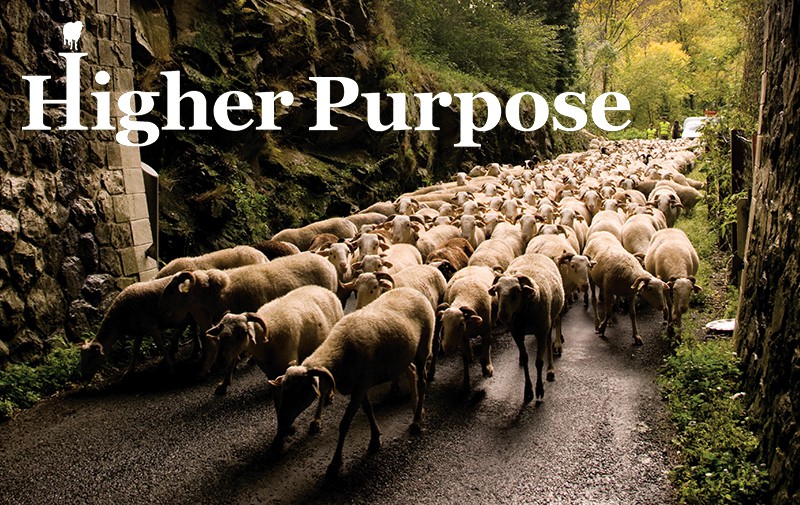

A flock of tarasconnais ewes start the climb to their summer pastures above the Vicdessos valley in the french Pyrénées.

Back in the 1990s I moved to the French Pyrénées from the United Kingdom, where I had studied photojournalism. And there I found these mountains, rising as high as 10,000 feet, full of stories just waiting to be told.

For centuries, farmers herded their animals up and down the mountains to different pastures each spring and fall, a journey they call the transhumance. After the Second World War, trucks gradually replaced the traditional ways of moving livestock, and young people left the mountain valleys for jobs in towns. The countryside was becoming a museum.

But about 20 years ago, local people revived the twice-yearly practice of transhumance as a way of breathing life back into the mountains. Since then, they have opened these marathon hikes to all comers, attracting visitors from near and far. They pack the cafés, stay in the guesthouses, and relish the local cheeses. The welcome is genuine.

The flock crosess the River Soulcem to reach the open mountainside which will be their home from June to October.

To join a transhumance is to be part of this revitalizing expedition. A typical transhumance may cover 40 miles or so, spread over three days, and climb to 6,000 or 7,000 feet. There’s a strong feeling of solidarity. Each farmer is helped by his friends and family. In due course, he will return the favor.

At midday there’s a stop to rest the animals, and the humans share a mass picnic. Cheese and pâté never taste so good as when thrust into my hand by a shepherd and accompanied by a crunchy chunk of baguette. As there’s still an afternoon climb to come, I always politely try to refuse the wine… but somehow a brimming tumbler finds its way to my hand anyway, with the words, “You’ll need some fuel for the afternoon.”

I’ve made friends on the way. When I’m standing with my back to the edge of a gorge, trying to get a shot, there’s always someone who jokes, “Too close, too close, move back a little…” Another will prod me with his staff as I’m about to press the shutter.

At the end of the day, there’s a village party with enough food to feed a small regiment—everything locally produced, of course.

I’ve come to be part of mountain society, living here rather than just observing from afar. I want to record this life in case it ever disappears, and, without the least desire to be pretentious, I like to think that I can help these people tell their story.