In a village in Basque country—the western region of the Pyrenees Mountains that straddles the France-Spain border—it’s easy to get lost in a maze of white walls and red shutters; houses aren’t numbered. Instead, you have to look for a name. Arrosa, Zubialdea, Irigoinia—the monikers reach back centuries, and all of the locals, even groups of strolling ewes, seem to know them.

Bestowed upon every house, the names often derive from words for geographic features, such as “edge of the valley,” “rocky place,” or “beside the bridge.” And just as the houses are defined by the landscape, in turn, the dwellings define their inhabitants.

“My name is Hervé Damestoy,” says one farmer, as we lead his sheep out to pasture in the village of Mendionde. “But for people from my village, my name is Hervé Menta, because Menta is the name of my house. Here we have a really big attachment to our origins—our houses, especially.”

The word “house” doesn’t quite capture the concept, however. In Basque (a native tongue still spoken by about 700,000 people), it’s baserri, a three-story, stone-and-oak structure with a gently sloping roof, overlooking arable fields, pastures, and forests. Instead of a living space separated from outlying barns, the entire farm operation is incorporated into one structure: stables and kitchens are on the first floor, bedrooms and living rooms on the second floor, and hay and produce storage in the attic. Historically self-sufficient, baserri-dwellers farmed grain, fruits, and nuts; produced cider, fodder, and flax; and raised cows and sheep. Little wonder that the word is rooted in herri, which means “land,” “home,” “people,” or “settlement,” depending on the context.

Naturally, cheesemaking happened in the baserri, too. As a child, Damestoy didn’t eat Idiazábal or Ossau-Iraty; he ate “house cheese” or “mountain cheese.” Made from whatever milk was available—usually raw sheep’s milk from local breeds such as the productive “red head” Manech; the sturdy, hardy “black head” Manech; the spiral-horned Basco-Béarnaise; or the wooly Latxa—these were rustic cylindrical wheels, uncooked, pressed, and aged.

“The older it was, the harder it was to cut, the better it was,” Damestoy recalls. “There was so much taste in that cheese.” In parts of Spanish Basque country, legend has it that cheese aged in houses took on a smoky flavor from the family fire, which is why Idiazábal and other wheels are sometimes lightly smoked to this day. Mountain cheeses were made similarly, in high-altitude huts (cayolars) during summer.

Modern Markets and Fragile Farmsteads

Today, though, things have changed; you won’t find anything called “house cheese” or “mountain cheese” in supermarkets. Farming isn’t easy, and in many parts of Basque country the price of land has risen while milk prices have stagnated. As fewer children become farmers, many families have split up baserris. Larger farms have bought out inactive properties; uninhabited buildings are left to crumble.

This trend has been traumatic for the region, and not only in an economic sense. The Basque have a concept called indarra, a spiritual energy that exists in every house and fuels life changes, from pregnancy to wine fermentation and rennet’s ability to curdle milk. The master of the house controls the indarra and must keep it intact; as a result, parents choose only one child to take over the baserri. This inheritance system encourages continuity and preserves heritage, as an undivided farmstead is considered the repository of Basque culture and values. With this in mind, deteriorating baserri take on a whole new level of symbolic significance.

But after centuries of fighting for sovereignty, the Basque are well-versed in safeguarding tradition. In this context architecture and language are more than just cultural—they’re political. The same might be said for cuisine.

“Food plays a key role in establishing and maintaining Basque identity,” says Elke Panneels, founder of culinary tour company Basque Taste based in Bilbao, Spain. “People discuss food here as passionately as others would discuss politics.”

Cheese, for example, has reflected the shifting political landscape on the French side of the border, where prospectors from the Aveyron region arrived in the early 1900s to set up modern facilities to turn local sheep’s milk into Roquefort. While this gave Basque farmers a reliable outlet for their products, it risked turning the region into a supplier of milk for cheese that was aged and sold far away, the benefits of added value realized elsewhere.

Basque nationalism reached a tipping point in the 1970s, when homegrown radical groups actively fought for sovereignty. Around the same time, French Basque farmers started developing an Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC, now AOP) for the cheese they’d grown up eating. They named it Ossau-Iraty after the Ossau Valley and the Irati Forest. A few years later—while the Spanish Basque region was enjoying an unprecedented level of autonomy following the death of dictator Francisco Franco and the restoration of democracy—sheep’s milk Roncal became the first food to secure a Denominación de Origen (DO, now DOP) in Spain.

“It was very important for us, establishing [Roncal] outside of our home,” says Miguel Aznárez Lus, who has been producing the cheese for 31 years in the Navarra region.

Bringing It All Back Home

How to ensure that the newly-minted AOC and DO cheeses wouldn’t be appropriated by existing factories, those built to process milk for cheeses like Roquefort? The strategy in French Basque was to develop two categories: a regular Ossau-Iraty that could be pasteurized, and an additional designation for fermier, or farmstead Ossau-Iraty, subject to stricter production rules. (For example, milk must be raw and come from a single herd.)

On the Spanish side, farmstead makers of Idiazábal formed the Artzai-Gazta (“Shepherd Cheese”) cooperative in 1985 to promote and ensure the quality of cheeses made by dairy farmers. Today, its 112 members produce more than half of all DOP-certified Idiazábal.

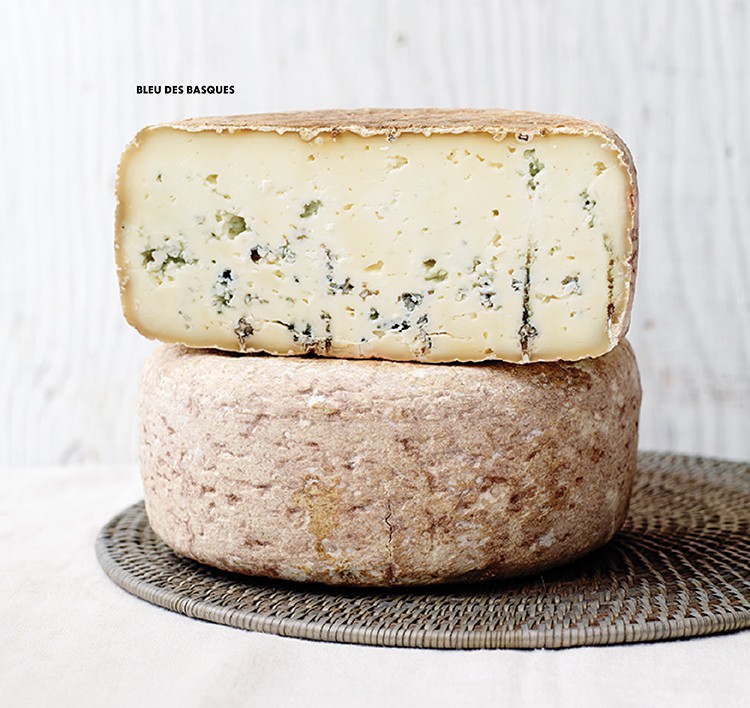

Many farmers, including Damestoy, still sell sheep’s milk to larger dairies such as French Basque–based Onetik or Agour. These modern facilities make protected Ossau-Iraty along with a range of other private-brand sheep’s milk specialties, such as the soft, sweet, blue-veined Bleu des Basques or the loaf-shaped Ardi Gasna.

While those cheeses are exported throughout the world, fermier versions are more likely found exactly where they’re made. Today the Pyrénées-Atlantiques area (encompassing French Basque) is one of the top farmstead cheese-producing regions in France. Meanwhile, in Spanish Basque, 95 percent of farmstead Idiazábal made by Artzai-Gazta cooperative members is consumed locally.

In the French Basque village of Ossès, I’m welcomed into the living room of Isidora Aldax, whose son, Pierre, is busy tending sheep. She removes a dishcloth from a stack of cheeses in the corner of the room. The wheels are far more rustic than Ossau-Iraty from modern dairies—they’re all different shapes and sizes, with holes and cracks in the paste and mottled rinds. “House cheeses,” she calls them. I’m not accustomed to shopping in people’s living rooms, but it makes sense: The center of Basque social and economic life has always been in the baserri.

After I buy another fermier wedge at Elena Monaco’s baserri in the village of Saint-Étienne-de-Baïgorry, she walks me to my car, waving back toward her home. “This is a Basque house,” she says proudly. “You see? It is very specific, very traditional. Despite everything, we have to preserve our traditions.”

This same sentiment surfaces in the closing lines of “Basseri,” Basque singer Iñaki Eizmendi’s 1966 ode to the homestead: “Euskal arrazik esta galduko, baserririk dan artean,” or, “the Basque race will not be lost, as long as there are farms.”

Tasting Notes

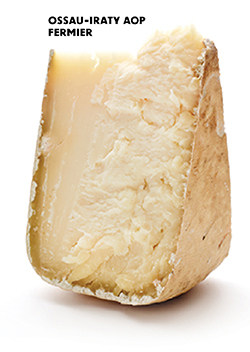

Ossau-Iraty AOP Fermier

- Maker: Les Fermiers Basco-Béarnais

- Origin: Accous, France

- Milk: Raw sheep’s milk

The super-thick, mottled rind hints of the funkiness to follow, although aromas are surprisingly subtle—faint whiffs of hazelnut, skim milk, and tropical fruit. The toothsome paste crumbles beautifully, and the powerful flavor is acidic and barnyardy.

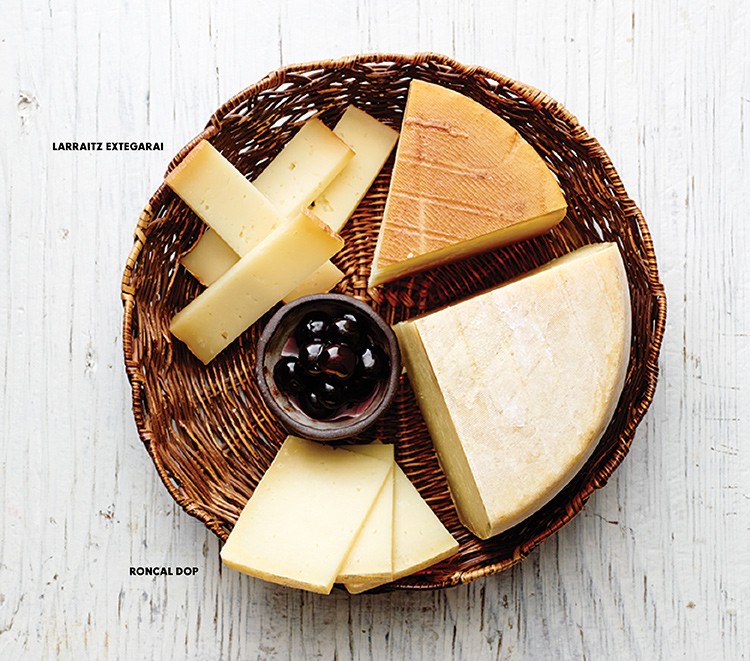

Roncal DOP

- Maker: Quesos Larra

- Origin: Burgui, Spain

- Milk: Raw sheep’s milk

Very firm and speckled with tiny holes, Spain’s first DOP cheese has a strong briny aroma. Flavorwise, its sheepy origins are on full display—gamy overtones give way to a slight piquancy and background notes of dried fruit.

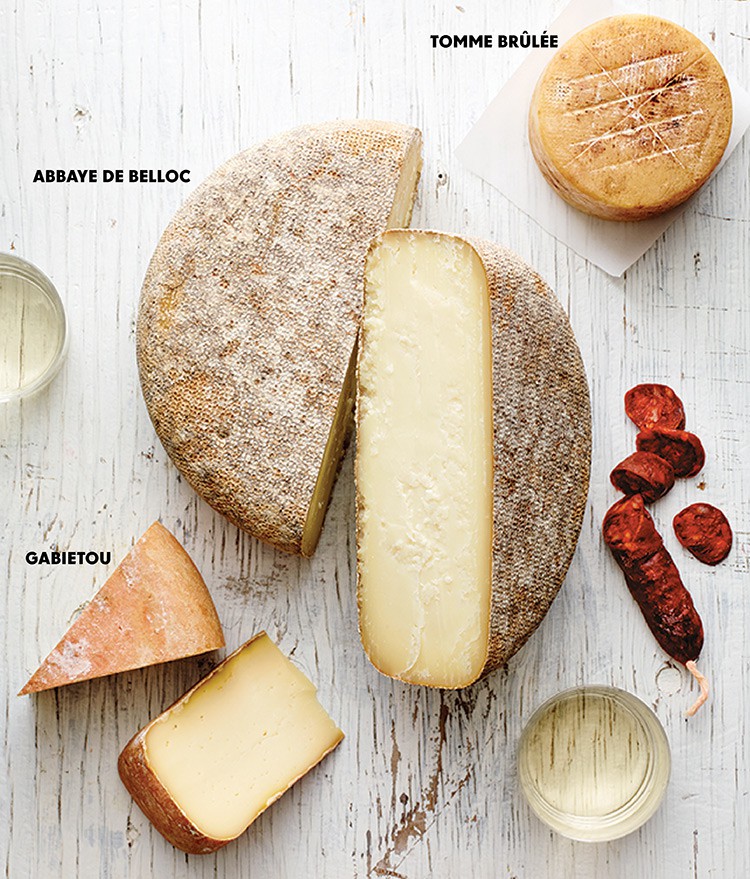

Abbaye de Belloc

- Maker: Abbaye Notre-Dame de Belloc

- Origin: Urt, France

- Milk: Raw sheep’s milk

This Ossau-Iraty–style cheese is made by Benedictine monks in the western French Pyrenees. It’s subtle in aroma but surprisingly robust in flavor, with a rollicking sharpness that recalls aged block cheddar and hints of sweetness that temper any acidity.

Idiazábal DOP

- Maker: Quesos Aldanondo

- Origin: Salvatierra, Spain

- Milk: Raw sheep’s milk

Idiazábal is all smoky bacon on the nose, but the flavor goes beyond campfire: The dense paste harbors notes of sweet pineapple with pleasingly bitter punches of citrus and pith.

Gabietou

- Maker: Fromagerie Agour & Hervé Mons

- Origin: Hélette, France

- Milk: Pasteurized sheep’s and cow’s milk

The paste is soft and fondantlike with a cellar-meets-apples odor. Flavors bloom slowly on the palate, with notes of almond milk and plum that extend into a long, meaty finish.

Bleu des Basques

- Maker: Onetik

- Origin: Macaye, France

- Milk: Pasteurized sheep’s milk

Deliciously sweet and tangy on the nose, its aroma recalls a big scoop of sour cream. Spotty clusters of gentle bluing punctuate the soft paste, which boasts lovely floral background notes and barnyardy vibes all around. Hints of grains, oats, and yogurt linger.

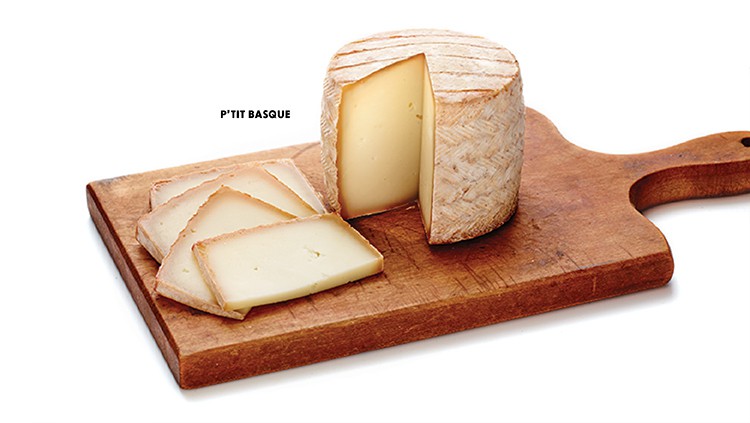

P’tit Basque

- Maker: Fromagerie Istara

- Origin: Larceveau-Arros-Cibits, France

- Milk: Pasteurized sheep’s milk

Smelling of a yeasty, salty cracker with a hint of barnyard, this diminutive wheel has a mild flavor up front followed by deep aromas of mixed nuts— almonds, hazelnuts, cashews—and a sweet finish.

Larraitz Extegarai

- Maker: Quesos Aldanondo

- Origin: Salvatierra, Spain

- Milk: Raw sheep’s milk

While the scent of honey-smoked deli ham hits you first, the firm paste is oh so snackable, with butterscotch notes, a tongue-tickling spiciness, and a tangy finish.

Tomme Brûlée

- Maker: Rodolphe Le Meunier

- Origin: Midi-Pyrenées Region, France

- Milk: Pasteurized sheep’s milk

Finished wheels are torched, hence the name (brûlée means “burnt” in French). Smelling salty and nutty with caramel-penuche sweetness, the paste has lactic notes with some back-of-the-palate spice.

Brique Agour

- Maker: Fromagerie Agour

- Origin: Hélette, France

- Milk: Pasteurized sheep’s milk

This loaf-shaped cheese has an ombré appearance, as the grey rind gradually transitions to a pale-yellow paste. Tangy, with background aromas of roasted cashews, warm milk, and eggnog, it has a round finish and dry wood notes.

Cheese photographed by Andrew Purcell, styled by Carrie Purcell