Photographed by Caleb Kenna

What would the Vermont dairy industry look like without immigrants from Latin America? For Will Lambek, an organizer at Burlington, Vermont-based nonprofit Migrant Justice, the answer is simple: “It wouldn’t exist, at least in its current form,” he says.

Vermont needs immigration because Vermont needs milk. It’s the state with the heaviest reliance on a single agricultural commodity. About 80 percent of its open land supports dairy production. Not only does milk drive the economy; it shapes the landscape. It creates the bucolic scenes that attract tourists, provides raw material for world-famous cheeses, and sustains traditions woven into the social fabric. It keeps hillside pastures green and lush, dotted with cows. It holds up majestic red barns that might otherwise crumble.

And behind those postcard-worthy facades are the hidden daily toils of the dairy farm workers. Their days begin well before sunrise. They often work between 60 and 80 hours per week. Cows need to be milked multiple times and manure needs to be shoveled, every single day, all year long. Holidays and vacations are scant. Summers are hot and muggy; winters are frigid. The work is dirty, isolating, and physical. It’s not glamorous.

Nor is it lucrative. Milk prices have been declining for decades, forcing dairy farms to consolidate, increase output, and find people to work at low wages. “The traditional model of the family farm—run by family members and maybe the local high school students picking up some shifts—is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain,” says Lambek. “In order to survive, farms are having to grow. And when they grow, they’re hiring immigrant workers.”

DAIRY DEPENDS ON IMMIGRATION

According to Vermont state representative Peter Conlon, dairy farms in Vermont really started struggling with labor about 20 years ago. In a state with a declining population, it became increasingly difficult to find enough locals willing to do the backbreaking work. “Even back then, dairy work was falling out of esteem in the general population,” he says. “There was a certain culture of saying, ‘Be careful or you’ll end up having to do that kind of work.’ But at the same time, farms were growing.

That’s when some immigrants from Mexico started showing up in the state, looking for jobs. “I think it happened organically,” says Conlon, who spent a decade working as a consultant at AgriPlacement, a company that connects dairy farm owners with workers, who are often immigrants. “A couple of guys from southern Mexico came to a farm, and through their informal network word spread that there were good, reliable jobs here.”

With unemployment in Vermont currently hovering around two percent, it’s as difficult as ever for farms to attract local staff. Today, almost 70 percent of milk in Vermont is produced on farms that utilize immigrant labor. There are likely around 1,500 migrant workers in the state, predominantly from Mexico and Guatemala, most working—and living—on dairy farms. “Had these guys not shown up,” says Conlon, “a lot of dairy farms would have shuttered for their inability to find reliable labor.”

The situation here is not unique; similar patterns exist in other dairy-producing states like New York and Wisconsin. According to a 2015 study from Texas A&M University, over half of dairy workers in the US are immigrants. At the national level, almost 80 percent of American milk is produced on farms that hire immigrant workers. While farm owners in many other agricultural industries can hire foreign farm workers through seasonal work visas, dairy farming requires labor year-round. Since there is no year-round visa program for farm workers, the vast majority are undocumented.

That puts both immigrant workers and farm owners in a very precarious position. When workers depart, efficiency wanes. Herd health declines. More calves and cows die. According to the same Texas A&M study, if immigrant workers were suddenly removed from America’s 58,000 dairy farms, 7,000 of those farms would close. Milk production would decrease by a quarter. The price of milk for consumers would nearly double. Direct economic losses would total $32 billion, with a rippling effect throughout the US economy. “Frankly,” says Conlon, “these immigrant workers have saved the dairy industry.”

THE OTHER BORDER

Despite the fact that they keep its dairy sector afloat, immigrant farm workers in Vermont are routinely targeted, detained, and deported. It might be far from the Mexican border, but proximity to Canada puts Vermont in a unique position. Within 100 miles of the Canadian border, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers can detain, search, and question anyone freely—rendering protections from “unreasonable search and seizure” null. Between 2013 and 2017, local CBP officers have arrested almost 400 people believed to have crossed through the country’s southern border. “We see an average of one detention from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) or border patrol every week,” Lambek says.

In a state that’s about 94 percent white, Latino residents stand out. CBP and ICE agents have acted on tips from “concerned citizens,” local cops, or even—controversially—Department of Motor Vehicles employees. In the vast majority of cases, no crimes or suspicious behaviors precede these tips. It’s racial profiling, and it begins as soon as immigrants step off the farm. In recent months, people have been arrested in Walmart parking lots, at McDonald’s, or even on their way to and from doctors’ appointments. News of these arrests ripples quickly throughout the immigrant communities.

It’s not hard to see the implications. “People feel like prisoners on their farms,” Lambek says. “If they go to the grocery store, to the bank, to go play with their children at the park, they could be subject to arrest, detention, and deportation.” A 2017 survey by the Open Door Clinic, which serves under- and un-insured individuals in Addison County, found that 80 percent of immigrant workers felt more scared or anxious to go out in public since the 2016 election.

University of Vermont anthropology professor Teresa Mares, who studies health among dairy farm workers, has found that the fear of going out is so pervasive that many immigrant workers are actually going hungry. “With people being galvanized into xenophobia by the highest levels of our government right now, migrant workers are expressing fear of being in public,” she says. “Very few farm workers are actually doing their own groceries.”

That leaves workers dependent on their employers and vulnerable to exploitation. A 2014 survey conducted by Migrant Justice found that 40 percent of immigrant dairy farm workers in Vermont were paid below minimum wage, almost a third routinely work for seven hours or more without a break, a quarter don’t receive a pay stub, and 15 percent had insufficient heating at home.

SPEAKING OUT

Still, the Vermont immigrant community has refused to stay silent. In 2009, when a young Mexican farmworker was killed on a Vermont dairy farm due to unsafe working conditions, a group of immigrants came together to form Migrant Justice. The nonprofit organizes farmworkers in human rights campaigns, takes legal action against racial profiling, and has successfully aided dozens of individuals who have been detained—both through public campaigns and support behind the scenes.

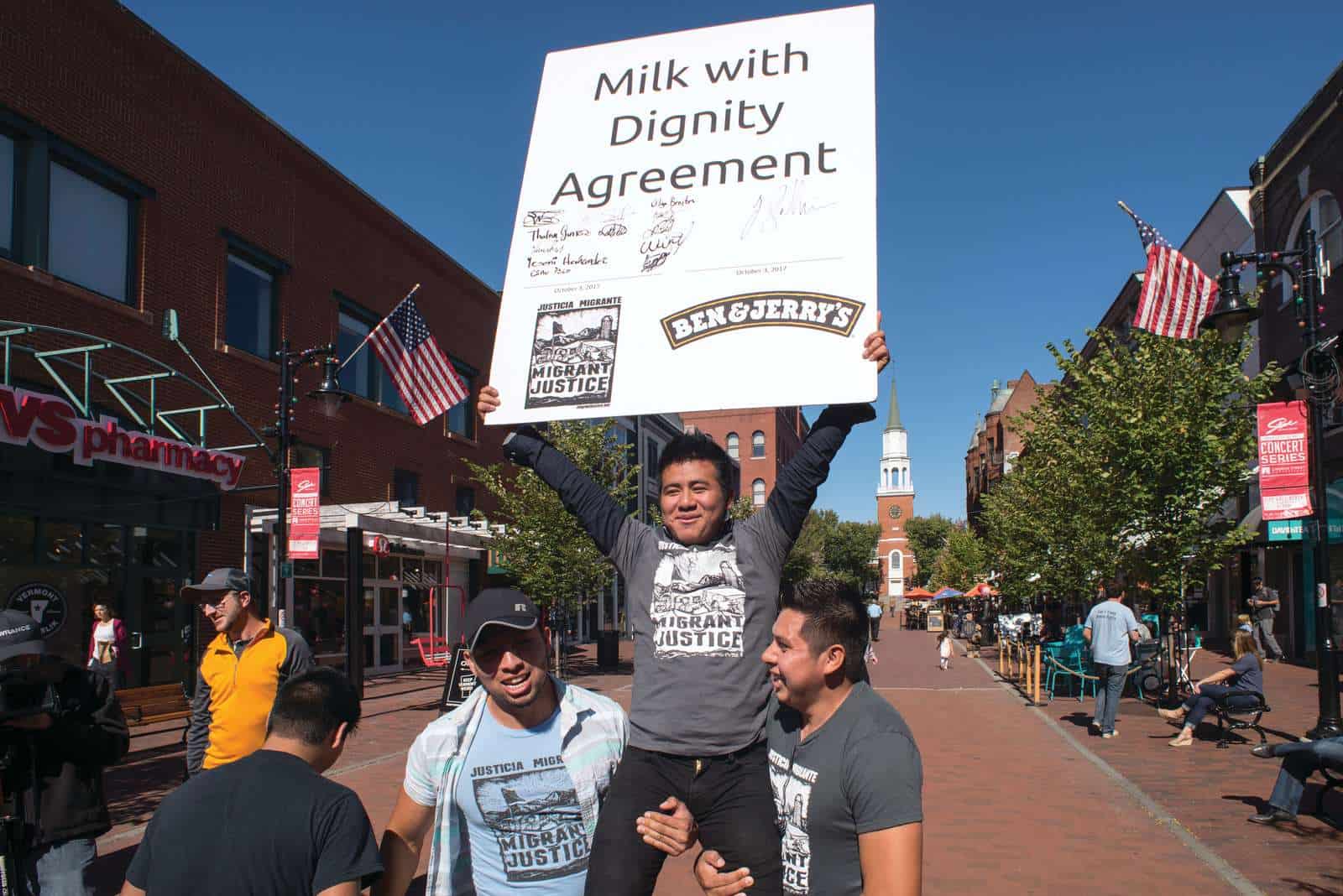

Migrant Justice’s leaders know that the fight for immigrant rights should begin where most of them live and work: on dairy farms. In 2017, after years of talks, pressure, and protest, the organization finally convinced Ben & Jerry’s ice cream—one of the largest milk purchasers in the state—to sign its “Milk with Dignity” agreement. Inspired by the Fair Food Program, a worker-driven social responsibility program that’s transformed the tomato industry in Florida, the legally-binding agreement provokes large companies to consider their milk sources and the conditions on their supplier farms.

“It was important to have a company like Ben & Jerry’s sign the agreement,” says Migrant Justice organizer Marita Canedo. “It’s a very proud Vermont brand, and they already had commitments in place for animal welfare and environmental issues—so it was time for them to take a step forward to secure protections for the farmworkers.” Under the agreement, Ben & Jerry’s now pays a premium for its milk; in return, farm owners follow a code of conduct established by workers to guarantee fair wages, scheduling, housing, health and safety, and the right to work free from retaliation.

By ensuring dairy farm workers have those basic rights, the program has already made a big impact. “There have been so many changes,” says Luisa, a dairy farm worker and member of Migrant Justice (to protect her identity, we are omitting her last name). “We didn’t have a day off before. Now we get a day off… now that I have my baby, I’m able to spend more time with her. Before, nobody cared if you got sick; we had to work and if we couldn’t, that day was taken off our paycheck. Now that we have Milk with Dignity, we’re paid that day. And that’s important for me, for all of us.”

Efrian, a worker at a Milk with Dignity farm in northern Vermont, says that one of the biggest changes has been the ability to stand up for himself without fear. “[Our bosses] are more interested in making sure that we’re comfortable and happy in our job,” he says. “I don’t have any reason to feel less than anyone else. It’s the opposite; I have the right to express what I feel to the boss without any fear that he’ll run me off the farm or call immigration on me.”

Migrant Justice’s leaders, who speak out publicly in spite of threats to their livelihood, have helped bring the lives of dairy farm workers out of the barns and into the spotlight—but it hasn’t been easy. Between 2016 and 2018, ICE and CBP arrested around 40 immigrants involved in the organization. “We’ve seen a clear pattern of ICE targeting Migrant Justice leaders for arrests and surveilling the organization in retaliation for the human rights work that we do,” says Lambek.

In 2017, ICE agents detained two activists, Enrique Balcazar and Zully Palacios, as they left Migrant Justice headquarters in Burlington. Following a rally outside immigration court, a petition with over 10,000 signatures, and 200 letters of support (including those from Senator Bernie Sanders and other elected officials), the duo was released—and they didn’t stop speaking out.” Our community has been criminalized for decades and little by little we’ve come out of the shadows by raising our voices,” says Palacios. “We know the risk, but it’s the only way that we can denounce injustices and empower our community. We all deserve to live freely and have our rights respected.”

Jose Luis Cordova Herrera, a Vermont dairy farm worker and father of three, was arrested and detained on his way home from a health clinic in 2018. Community members condemned the circumstances of the arrest as an attack on his right to access healthcare. Nearly 1,500 people wrote to ICE calling for his release. Eventually, he was freed on bond, which fellow dairy farm workers raised the money to pay for. Upon his release, Herrera reflected on the experience in a public statement. “I came to realize how important it is to be part of an organization like Migrant Justice,” he said. “My freedom is proof of the power of an organized community.”

This is a very informative and well-written article about a local issue with national implications. Thanks for the education!