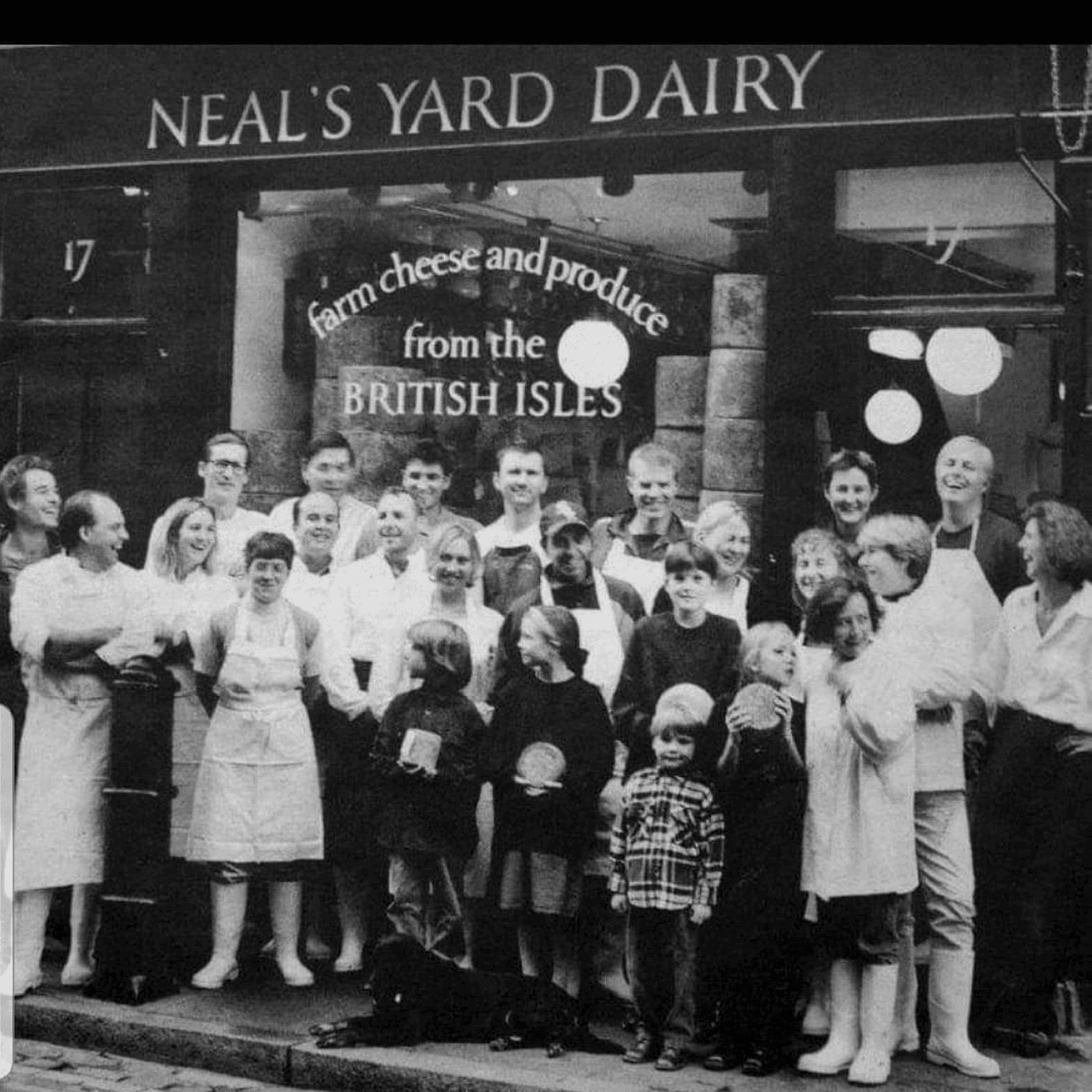

Kate Arding is a name that resonates far and wide within the cheese industry. From her early days working behind the counter at storied institutions such as Neal’s Yard Dairy and Cowgirl Creamery to co-founding culture magazine and serving on the board of the American Cheese Society, Arding’s career has kept her at the forefront of the farmstead cheese movement.

Arding’s journey has been marked by a seemingly endless series of exciting projects, taking her all over the country and world in the pursuit of championing cheese and the people who make it.

Since 2014, Arding has channeled her enthusiasm for cheese into Talbott and Arding—the “so much more than cheese” cheese shop she co-founded with partner Mona Talbott—in Hudson, New York. We caught up with Arding to talk about her remarkable career, why you should care about raw-milk cheese, and the overall state of artisan cheese.

culture (CM): You’re one of the co-founders of culture, so I would love to talk a little bit about the initial idea to start the magazine. I’ve heard that it was conceived over a glass of wine with sisters Stephanie and Lassa Skinner while you were brainstorming for a project. Starting the first American magazine dedicated to cheese seemed like a crazy idea, and certainly one without a blueprint to follow—which could be said for much of your career—did it feel like a wild endeavor at the time?

Kate Arding (KA): It was conceived over a glass of wine. I was living on the West Coast and was really good friends with Lassa—we helped open the Oxbow Cheese and Wine Merchant together, and I’d never met Stephanie, but I knew she was in publishing.

It was definitely an original idea, but of course in the lead up to the first issue, we learned about Cheese Connoisseur—the timing was almost identical. We were a bit surprised when we heard that, as you can imagine. But it actually ended up being really great in a bizarre way because it served to convince advertisers there was a market, because there were two magazines happening.

I suppose it was a bit wild, but it wasn’t that wild, you know. We felt that there was a need for it, we viewed it as an extension of cheesemongering because there’s such an educational component involved. It was initially aimed at the consumer—I don’t think any of us anticipated the extent to which the industry would latch onto it.

CM: It’s interesting that you guys thought it would be more focused on the consumer than the trade at the time.

KA: Yeah, but it very quickly evolved. And I think that’s a tremendous validation of the magazine. Because if you’re writing or photographing for your peers, it’s a different dynamic. But we couldn’t get too nerdy because it also had to be understandable to the consumer. So that’s where the extension of cheesemongering came in.

CM: You have had such an illustrious career. Looking back, is there one achievement you are most proud of?

KA: Honestly, there isn’t one thing. I think the big takeaway for me is that I’ve been so lucky to be part of a great number of really cool projects—and they all involved teamwork. Landing at Neal’s Yard Dairy was so exciting to me at that time because it was such a moment in food history with the UK and what was happening there. There were some really great moments during that tenure, such as getting the account for Buckingham Palace. I’m very proud of what we achieved there, but it was a collective effort.

And then I think of the big adventure of moving to California and helping Sue [Conley] and Peggy [Smith] start Tomales Bay Foods, which again, was so exciting. Witnessing and being part of that enormous evolution with cheesemakers in California— when I moved there, you could count them on one hand. I certainly didn’t do that on my own, but being part of that change has been really wonderful for me.

I love cheese and I love connecting people and making stuff happen. I think that’s what I’m most proud of, keeping the focus on the producers and championing them.

CM: You opened Talbott and Arding in 2014 with your partner Mona Talbott. What has it been like to open and run a business with your partner? Can you share some of the challenges and rewards?

KA: I have to say, I was really worried beforehand. Mona is the creative culinary force whereas I focus on cheese and on operations. We work really, really well together. I remember listening to an interview with Andy and Mateo Kehler [of Jasper Hill Farm], this was years ago, and Andy said, “Mateo’s really good at finding cliffs to jump off. And I’m busy sewing the parachute.” And that’s kind of how we work.

CM: So, is Mona the one jumping off the cliff?

KA: Yes, and I’m the one sewing the parachute. There’s a division of labor, our work ethic is the same along with the vision. All of which is key. We disagree occasionally, but never fight. We have huge respect for each other and the other’s opinions.

CM: Having lived and worked in several seriously food- oriented places, including London, California, and now the Hudson Valley, what was it about the Hudson Valley that made you want to put down roots here?

KA: I initially moved to the East Coast for cul ture, and then Mona came back into my life after spending six years founding the Rome Sustainable Food Project at the American Academy in Rome.

Mona had an idea to start a food school in the Hudson Valley. It was going to involve classes on cheesemaking, canning, preserving, baking, and was primarily aimed at food professionals. She was in the process of getting an advisory committee together when I entered the scene.

We quickly began to realize that this was a huge project and beyond our experience to be able to pull it off.

Even though we’d both worked for highly respected companies or organizations, neither of us had any track record with running our own business. And one of the members on the advisory board wisely said to us, “Take a piece of it that you know you can succeed with and go with that. That will show investors that you can run a business and get you estab- lished in the local commu- nity.” So that’s how we ended up with the shop here.

Also, it made a lot more sense to be close to our suppliers and producers, and we wanted to put down roots in the Hudson Valley, so it just made sense.

CM: It is a running joke in the cheese industry that no one got into this line of work to make money, but behind that joke is a very real problem many producers and retailers are grappling with on a regular basis. Do you have any advice for people trying to make it in an industry with such tight margins?

KA: I think the simple—well, not simple—but the one answer I would give is ‘value add.’ It isn’t everyone’s bag, but it’s the key these days. For example, Sugar House Creamery up in the Adirondacks has an Airbnb on the farm, and Italy with its history of agritourism. Even if it’s a little shop or a café or a farmers’ market, people want the experience. Some kind of value added is the key.

CM: Interesting. When I hear value add, my head goes to adding a new product line.

KA: Absolutely, it used to mean that. But to me, now it’s bigger than that. When we were starting this business, we were very clear with ourselves that we had to have multiple revenue streams. If we just relied on retail, we wouldn’t make it, which is why we do catering, wholesale, and mail order.

You have to be nimble and pay attention to what people are looking for. Mona has an extraordinary knack for being able to predict market trends, which is wonderful, but you have to pay attention to what people are interested in.

It does require a lot of customer-facing interaction. And a lot of producers aren’t comfortable doing that. You know, they’re very happy living remotely or in a rural location. So, if that’s the preference of the producer, it’s better to find somebody who likes customer interface. I would encourage them to partner with somebody, maybe a family member or friend, who’s more into it.

CM: You are incredibly passionate about the preservation of raw-milk cheese. Why do you think raw-milk cheese is deserving of greater appreciation and protection?

KA: I think it’s about the knowledge that goes with it. I think it has the capacity to be superior if it’s made in a really good way, but it’s not inherently better just because it’s raw milk. I’ve tasted some really awful raw- milk cheeses, and I’ve also tasted some really wonderful pasteurized cheeses.

I think the driving force is the knowledge and the history and the context around it, and the microbial diversity. To lose that institutional knowledge and that microbial diversity would be devastating—and that applies to other fermented foods as well.

CM: Your work has taken you all over the world. Is there one trip that sticks out in your memory? Perhaps because of how it shaped your perspective on food?

KA: There have been so many trips… I’ve been really fortunate to go to some incredibly cool, unusual, and challenging places. But it’s not always the most exotic ones that have the most impact.

This is going to sound odd, but one of the most profound trips that I had was really early on when I was at Neal’s Yard Dairy. We used to do cheese runs, we’d actually go and pick up the cheeses— which was a huge treat—and I remember doing a trip with Randolph, the owner.

We drove all the way up to Scotland, stopping off at Mrs. Kirkham’s and Colston Bassett Dairy, and then all the way up to Isle of Mull. It was an incredible trip, about a week long. On the way, we stopped to see Humphrey Errington at Errington Cheese, who created Lanark Blue, and he had just had a whole problem with listeria, which temporarily stopped his production. He was really in a tough place and meeting with him was incredibly meaningful.

I remember coming back— you know, car journeys are always prime conversation— and Randolph had this habit of throwing these questions out—so we were on the return journey, and he said, “So, what have you got out of this trip?”

I thought about it for a minute and I said, “It just makes me want to sell cheese.” It sounds so simple to say that, but there was something about that trip that I identify as really being the spark to make me want to stay with it. It made me want to advocate for cheesemakers and protect what they’re doing and help them sell more cheese.

CM: What do you think is the biggest challenge facing cheesemakers today, and how can the industry work together to address it?

KA: Unfortunately, there are multiple challenges within our industry. One that concerns me greatly is that it’s becoming harder and harder to create a viable succession plan for smaller and medium-scale businesses as their founders retire or want to take a well-deserved step back. These are smart, hard-working, dedicated, and entrepreneurial people who created the core foundation of the vibrant artisan cheese scene we now find ourselves in. If we lose sight of the original vision and mission of these trailblazers, it will be to our detriment.

Simultaneously, over the past ten years, we have witnessed a significant trend of consolidation. This is happening especially with cheesemakers and with distributors, but also with other related businesses such as culture houses.

This consolidation, combined with the vacuum created by cheesemakers wanting to retire or get out of the business, is causing the landscape to change significantly. We will inevitably end up with fewer small producers, much less diversity of product, less microbial diversity, and a loss of knowledge around traditional cheesemaking practices, particularly with raw-milk cheeses, which are at greatest risk.

This said, I am greatly encouraged by a small, dedicated number of younger cheesemakers who are on the scene and really starting to have an impact. We need to ensure their future is secure.