The music industry likes to fight about intellectual property. Artists need permission to cover or sample a song and pay fees and royalties when they do. This borrowing can boost the popularity of the original song—as happened with Weezer’s take on Toto’s “Africa” in 2018— but not always. Rick Astley, whose 1987 hit “Never Gonna Give You Up” is the stuff of meme legend, recently sued a rapper for covering his song so perfectly that it was indistinguishable from the original. Instead of an homage, Astley saw it as a theft.

What does all this have to do with cheese? A musician’s value lies in their authorship. Cheese is a different story—the wheels we know and love have been collaboratively honed by hundreds if not thousands of people over the centuries. But, oftentimes, that honing was done in just one area, whose cheesemakers may not see it as such a group effort.

American cheesemakers like to riff on other countries’ offerings, making everything from chèvre and queso fresco to brie, manchego, and gruyère—of course gruyère. You don’t need to follow cheese news to have heard the grumblings about gruyère. Even the mainstream media covered Interprofession du Gruyère v. US Dairy Export Council, a case that lasted over a year, underwent multiple appeals, and tackled questions such as: Can a country be an author? And if so, how long is their product “theirs”?

A seemingly final verdict was reached this March, but the fight feels far from over.

YEAR IN REVIEW

For many, the situation began in 2021, when the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) denied trademark protection for Gruyère. But for its Swiss makers, it started a little earlier than that—in the twelfth century, in a town called Gruyères, where the legendary wheels were first made.

In the present day, these Swiss makers joined forces with French producers of Gruyère to file a joint appeal of the decision to the US Trademark Trial and Appeal Board, who also denied them, citing, among other things, the World Championship Cheese Contest’s celebration of gruyère from all over the world.

This partnership of Swiss and French was an unusual one. The two countries have not always been friends in Gruyère— both carry a country-specific Appellation d’Origine Controlée (AOC) for the cheese they produce, but Switzerland took issue with France applying for the European Union’s Appellation d’Origine Protégée (AOP). The Swiss felt if anyone should be getting a Europe-wide AOP designation, it should be them, and the EU agreed. But this all seems to be water under the bridge now.

“The application … was jointly filed,” says Denis Kaser, a representative of the Interprofession du Gruyère, “because the Gruyères region straddles the border of Switzerland and France.”

In January 2022, US District Court Judge T.S. Ellis III ruled against the Swiss/French team, stating that gruyère need not come from Gruyères, Switzerland, because Americans don’t associate the word with that region. “Decades of importation, production, and sale of cheese labeled gruyère produced outside the Gruyère [sic] region of Switzerland and France have eroded the meaning of that term and rendered it generic,” he stated in his opinion. (US law does not allow for the trademarking of generic terms.)

France and Switzerland filed another joint appeal in December. “Whether Gruyère is a generic term depends on how it is understood by a majority of consumers,” their argument stated, specifying that “the other parties had no evidence as to how Gruyère is understood by a majority of consumers.”

On March 3, 2023, the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit upheld the USPTO’s decision, putting what many saw as the final nail in the coffin of the Swiss/French hopes of protecting their good name.

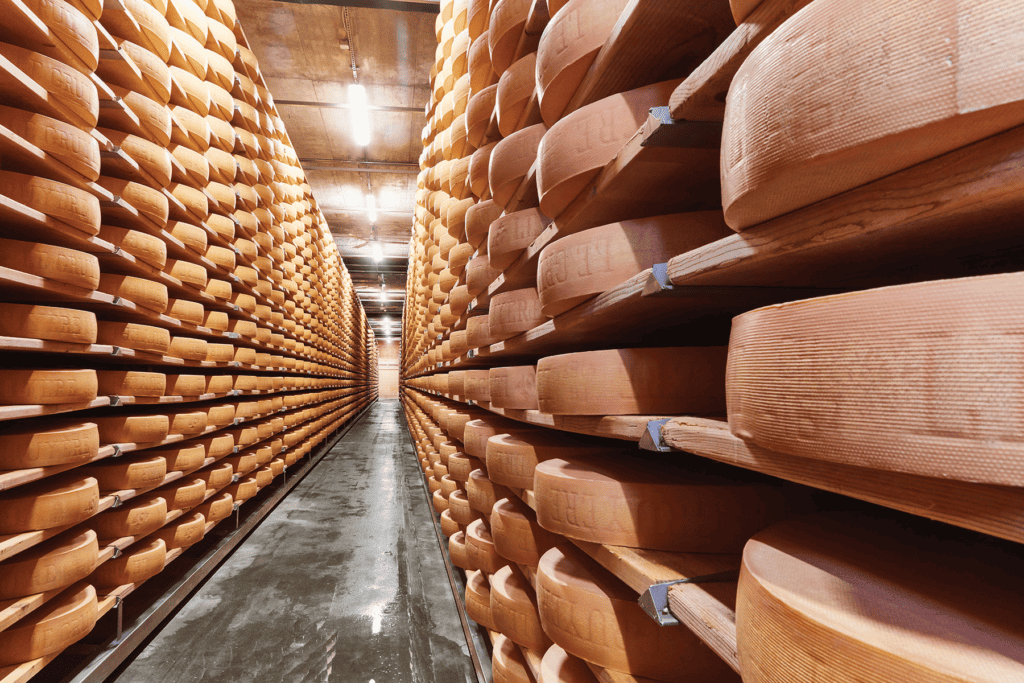

Every wheel of Le Gruyère AOP bears the name of the cheese on the rind, or “heel”

PDO, DOP, AOC, AOP … WTF

OK, so you’ve wrapped your head around why Europeans put letters at the end of cheese names—they’re geographic indications (GIs), also known as quality schemes, designed to tell you you’re buying the genuine article. But what do all the different letters mean? We made you a cheat sheet.

- PDO — Protected Designation of Origin the English translation of the European Union’s GI, established in the 1990s when the EU was formed (prior to that, all countries had their own GI)

- AOP — Appellation d’Origine Protégée is simply the French translation of PDO, i.e., the GI awarded by the EU

- DOP — Denominazione di Origine Protetta, or Denominación de Origen Protegida, the respective Italian and Spanish translations of the EU’s PDO

- AOC—Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée, the designation awarded by French-speaking countries, such as France and Switzerland, to their products since around 1905

- PGI—Another EU designation, but one with less strict guidelines than the PDOs; in PGIs, only one phase of production needs to be carried out in the designated region

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Reading a summary of this case, you’re left with more questions than answers— chief among them: What makes something “generic”?

“A generic term is one that members of the relevant public understand as identifying the type of product rather than its source,” says Jaime Castaneda, an Executive VP for US dairy lobby National Milk Producers Federation and executive director of the Consortium of Common Food Names (CCFN). “In this case, the court determined that cheese consumers in the United States understand ‘gruyère’ as identifying a type of cheese, rather than as a signifier that the cheese was produced in the Gruyère [sic] region.” A term once protected as a trademark can become generic, he explained, if it ceases to bring to mind the source of the product but rather just a type of product (think: aspirin, escalator, linoleum). The music equivalent of this is the public domain— songs (and books, too) enter the public domain about 70 years after the death of their author. After that point, they’re fair game for copying.

“What they’ve done in Europe is they’ve taken generic names and made them non-generic, basically trademarking them,” says Errico Auricchio, an Italian expat who runs the Wisconsin cheese company BelGioioso and has worked with Castaneda at CCFN. “[The Italians] claim that Parmigiano Reggiano has been made for a thousand years, so obviously it was generic before they trademarked it!” (Auricchio says he didn’t get any legal pushback from the Italian PDOs when he began making parmesan, asiago, and fontina in the States.)

“The excuse given is the geographical area, which doesn’t mean anything; it’s political,” Auricchio says. “The geographic areas are not born by themselves, they were created.”

On the homepage of CCFN, a prominent credo reads: “Common food and wine terms—like parmesan, bologna, or chateau—are used on thousands of products around the world to accurately guide consumers to foods they know and love. Europe wants to monopolize these terms to unfairly stifle competition.”

But what CCFN describes as a monopoly is a tradition in Europe. AOC and AOP consortiums set strict production regulations for cheeses bearing certain names, an attention to detail one could argue is at least partly responsible for their global reputations and longevity. And here in the States, there’s a precedent for respecting this. We don’t, for example, let any Americans make a cheese called “Roquefort,” and makers here must call their hard Italian grating cheese “Parmesan,” not “Parmigiano Reggiano.” I asked Kaser if “groo-yair” was a possible workaround.

“We would not be comfortable with that,” he said. “American cheesemakers should not be permitted to market their cheese as Gruyère, or any alternate spelling of that name.”

Castaneda feels this makes things tough for American makers. “Consumers look for parmesan, not ‘hard grating cheese,’ or for feta, not ‘salty white cheese,’” he says. “Preventing producers from using names like those would put our producers at a significant disadvantage.” In this scenario, a customer shopping for gruyère would pick up anything labeled as such, ignoring American products labeled “Alpine style” or even “inspired by Gruyère.”

This name-dropping (cheese’s closest analog to cover songs) is already in use in many supermarkets. New Jersey’s Schuman Cheese describes its Altu as “inspired by Gruyère,” while Vermont’s Consider Bardwell Farm says its Rupert is “inspired by Gruyère and Comté.”

“Gruyère is the name of a specific Alpine cheese that has stood the test of time, reflects the taste of a place, and should have the right to its own name,” says Consider Bardwell co-owner and founding partner Angela Miller. “We named our Alpine style Rupert [for a nearby town] because our cheeses reflect the taste of our own little corner of rural, mountainous Vermont … our unique soil composition, weather, and native grasses.”

There are also producers who push it a little further, selling “American gruyère,” “Cheddar gruyère,” and “Wisconsin gruyère.” The last is what Cheese Brothers founder and president Eric Ludy uses at his operation. “There’s a long, rich history of Swiss cheesemakers bringing their techniques and standards of quality to Wisconsin,” he says. “My own great grandfather Fred was a Swiss cheesemaker who opened up some of the first cheese factories in my area of northern Wisconsin.” I heard this ancestral defense from many American cheesemakers working with recipes passed down to them by first-generation ancestors, many from—you guessed it—Europe.

“I came from Italy,” says BelGioioso’s Auricchio. “I brought the culture and the knowledge and understanding of what the cheese is supposed to taste like.”

Ludy agrees: “The United States is a nation of immigrants … our forebears took the names of their cheeses and brought them with them when they came to this country,” he says. “We’re not stealing the names or mimicking the styles. We are rooted in the same traditions as our European cheesemaking friends are!”

This is especially true in the case of Wisconsin cheesemaker Emmi Roth, the US arm of Switzerland’s largest exporter of Gruyère to the States, Emmi Group. Emmi Roth makes a line of Alpine-style cheeses that were originally marketed in the US as “Grand Cru Gruyère,” but in 2012 the name was changed to “Grand Cru” at the request of their parent company and the Swiss Gruyère industry. As reported by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel at the time, the change reflected the fact that the cheese wasn’t made in the Gruyères region of Switzerland and that, although the cheeses are similar, they do not taste the same.

“Since 2013, we have not used the word ‘Gruyère’ in … cheeses we produce and market locally in the US or in any of the brands controlled by our US subsidiary Emmi Roth,” says Simone Burgener, a spokesperson for Emmi Group. However, brands that purchase Roth’s cheeses and package them under their own labels don’t always follow these rules. “We point out the legal situation and the risks to clients and recommend that they refrain from using ‘Gruyère,’” she says, “[but] we ultimately have no influence on how, under what name, and at what price such private labels are sold by retailers.”

THE NEXT CHAPTER

Kaser declined to remark on his twice-defeated legal team’s next steps. Burgener spoke for Emmi Group in expressing unmeasured disappointment about the decision to consider Gruyère a generic term: “For consumers in the US and the marketing of this traditional Swiss cheese speciality there, this represents a step backwards.”

For his part, Castaneda is not opposed to European geographic indications (GIs) and is hopeful about the possibility of establishing guidelines that will benefit everyone involved. “We encourage GI holders to create a genuinely unique name by combining the name of their region with a type of cheese, just as many have successfully done in Europe,” he says, pointing to Mozzarella di Bufala Campania and its generic “mozzarella” as an example.

Though the Swiss and French seem more concerned with their proprietary rights as the original makers of this historic product, there’s also the matter of money. It stands to reason that a consumer reaching for a block of American gruyère is a consumer not reaching for a block of European Gruyère… right?

“This is purely fantasy,” says Auricchio. “There are markets for different things at different prices. If their cheese is superior and appeals to the American consumer, they will sell more. Their pride is going to be hurt, but only their pride. Not their bottom line.”

Unsurprisingly, Castaneda agrees: “The Swiss and French producers of Gruyère are free to compete on the same level playing field … [they] were the ones looking to tilt the balance,” he says. “The US produces plenty of parmesan in this country, yet Italy exports tremendous volumes of Parmigiano Reggiano to this market … Italy’s selling more parmesan than ever in this country. The Swiss and French Gruyère producers have similar opportunities to benefit from our market here.”

It’s a rising-tide-lifts-all-boats argument, one that American producers have plenty of examples of. “Very, very little Asiago comes from Italy,” Auricchio says. “Asiago has become a very popular cheese in the United States because of companies like ours, or Sartori, so really Italy has done nothing to create the business for Asiago.” But, as is true with a cover song, this equation only works if the consumer is aware of the original version.

THE CUSTOMER IS ALWAYS RIGHT

There’s a lot of talk of the consumer in these debates—confusing the consumer, guiding the consumer, clarifying for the consumer. Are we selling consumers short? Artisan cheese is, after all, all about taste, and taste is inherently, deeply individual. You like what you like, no matter who made it.

Though it’s probably easier for someone on the winning team to say so, Ludy is ready to put his faith in people to buy the cheese that’s right for them. “A consumer looking for traditional Swiss or French Gruyère will know to look for it and to take things such as appellation badges into account,“ he says.

If you’ll permit me to stretch the music analogy one step further, this scenario brings to mind Taylor Swift, who is currently recording new versions of her old albums to divert income from her former label. I’m ashamed to say I still listen to the originals. The new “Taylor’s version” songs have an uncanny valley quality to them, like fake meat, or vegan cheeze. Some Swifties opt for those out of loyalty, just as certain Americans prefer to buy from beloved farms and makers at home. But for some, it doesn’t matter how close the copies get—there’s nothing like the real thing, baby.

Le Gruyère AOP

To get Switzerland’s official AOP stamp, cheesemakers must follow a couple of rules… OK, more than a couple:

- Made in cantons of Fribourg, Vaud, Neuchâtel, Jura, administrative district of Jura bernois; and in the following communes of the canton of Bern: Ferenbalm, Guggisberg, Mühleberg, Münchenwiler, Rüschegg, and Schwarzenburg

- 70 percent of cattle forage from the farm

- No silage (fermented grass or grain)

- Permitted foods: grass, green rye, oats, green maize, fodder mixtures of vetch, rapeseed, raw potatoes, fruits with pips, chopped maize, leaves and collars of fresh beetroot, wheat bran, dry beet pulp, cereals, oats, hay, straw

- Milk delivered to dairy twice a day

- No additives, preservatives, or growth hormones used

- All milk traceable to specific farm

- Milk sourced maximum 12.4 miles from dairy

- Milk used within 18 hours of milking

- Only raw milk used

- Milk heated in open copper vats

- Curds pressed minimum 16 hours

- Aged in Switzerland at 12 to 18 degrees Celsius, on unpolished spruce shelves

- Wheels rubbed with salt and turned daily at start of aging

- Aged at least 5 months

- Round wheels with smeared crust, uniformly brownish, with a slightly convex heel

- Composition 49 to 53 percent fat, 34.5 to 36.9 percent water, 1.1 to 1.7 percent salt

- Holes in cheese desirable but not required; paste slightly damp, springy, not crumbly, ivory in color

- Salty flavor with fruity notes