Herstory is repeating itself at Hawkstone Abbey Farm in Shropshire, England, as an Appleby woman once again looks to the past to find a way forward for farmstead Cheshire cheese.

Trailblazing British cheesemaker Lucy Appleby, with support from her husband, Lance, bucked mid-20th century industrialized cheesemaking trends like waxing for worldwide distribution to make her internationally lauded Cheshire cheese in a traditional style. She sidestepped national dairy marketing board mores by driving a Land Rover full of truckles (the name for the cylindrical shape of Cheshire cheese) three hours southeast to Neal’s Yard Dairy and Paxton & Whitfield cheesemongers in London.

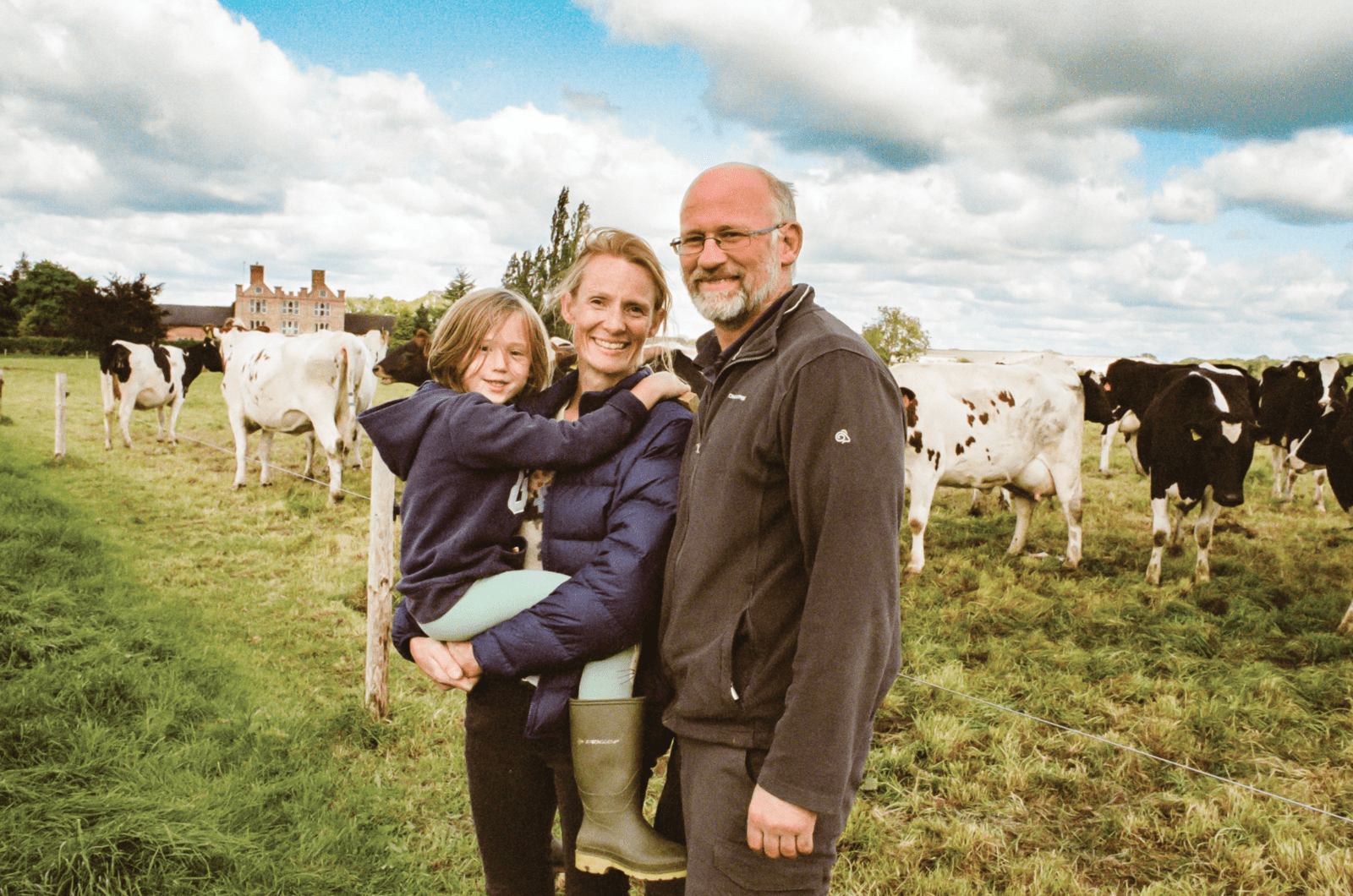

Today, Sarah Appleby and husband Paul, Lucy’s grandson, eschew environmentally destructive farming techniques to produce the key ingredient for the world’s last regularly made, raw milk, clothbound Cheshire cheese. “Lucy was a massive champion of traditionally made cheese. Honest cheese. She proved its value to wide customer base,” says Sarah. “We’re adding protecting the land as a part of the cheese’s overall value. We owe this to our farm, because the flora and the fauna in this specific place helps drive the character of the cheese.”

Traditional British cheeses maintain a fragile link to the past; they are edible representations of a deep but often forgotten agricultural and regional history. “Traditions cannot stay still, if they do, they die,” says Jason Hinds, director of sales at Neal’s Yard Dairy. “Evolution and innovation are so important to whether a cheese ultimately survives.”

FARM AND FAMILY

Cheshire cheesemaking has been woven into the cloth of Appleby family life for five generations. It stands in rotation with bursts of back-breaking farm work, reflective cups of tea, and mad scrambles to homeschool during the pandemic the current set of Appleby children inhabiting the farm, four boys and a girl, aged 16 to 6. It starts at 6:30 a.m. when fresh whole milk taken from the 350-strong herd of cross-bred cows flows from the milking parlor into a giant vat in the cheese room, once the farm’s stables. Cheshire is made by combining higher-fat evening milk and lower-fat morning milk, a mixture that gives the finished cheese a texture that is both crumbly and moist, almost juicy, says Sarah.

Before he begins his work, head cheesemaker Garry Gray fills three glass bottles and passes them through a hatch in the wall between the dairy and the farmhouse kitchen where the noise of the Appleby family and the scent of coffee and bacon fill the air. Garry learned to craft and cure Appleby’s Cheshire from Lucy. He works calmly, methodically, to stir in a small amount of house-made starter. It seeds the finished cheese’s mild acidity. He adds animal rennet to force the curds and annatto for the color, a distinctive sunset pink. As he breaks for tea and waits for the curds to cure, Garry expresses enthusiasm about this batch. “The quality of the milk is great; the cows have had an optimum mixture of feed and grazing and there has been a perfect amount of rain,” he says.

Garry and Paul work in silent tandem to carefully cut, stack, salt, and mill the curds. They ladle them, finely crumbed, into the Appleby’s telltale cloth-lined molds and place them to sit overnight in century-old, wrought-iron presses, painted forest green. Garry drains off the whey to be strained once more for remaining cream, which is then churned into salty, golden whey butter, a product the farm has recently begun making again after a 30-year hiatus. The twice-strained remaining whey goes to feed the pigs.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

While the recipe remains relatively unchanged over time, farming practices and conservation efforts at Hawkstone Abbey Farm are evolving to be more regenerative, rather than intensively industrial—through which tight animal quarters, processed feed production, and increased antibiotics usage levy a heavy tax on the environment. Old presses, now rusting, dot the farm like an historic art installation. Old cheese vats, repurposed as troughs for the now-grazing cows, signal a more sustainable future.

“For us, innovation means having to be better,” Sarah says, standing next to the Napoleonic-era barn, where Appleby cheeses—the colored Cheshire, a white Cheshire more popular in northern England, and Double Gloucester—mature today. “Innovation on the farm is about being more efficient with what we’ve got. It is not new by any means, we are almost going full circle—heading back to a way of farming our great-grandparents would have recognized,” says Sarah, who was raised on an organic dairy farm in south Shropshire.

The Applebys are in year four of a 10-year plan devised with the help of their mentor, Peter Long of Whitchurch-based P&L Agri Consulting, to embrace regenerative milk production. (Whitchurch is the market town from which all the Cheshire cheese used to be distributed around the UK.) In the United States, regenerative farming is well established at farmstead cheesemakers such Jasper Hill Farm in Vermont and Crave Brothers Farmstead in Wisconsin; however, the practice has been slower to catch on in the UK with Appleby’s being one of the first big dairy farms to adopt a comprehensive plan.

The starting point was to make grazing as accessible as possible for the herd. The farmhouse and milking parlor conveniently sit right in the middle of the 300-acre farm, and a total of 30 paddocks now spread out from them like a spider’s web. The cows take paths defined by repurposed railway ties that lead them to and from their rotating feeding grounds. From early March to early November, the herd feeds on clover, chicory, and plantain grasses. The greenery provides a filling, nutritious salad for the cows. And the plants’ deep rooted, drought tolerant, mineral-rich, perennial nature boosts the health of the soil, thereby increasing its capacity to pull some of the carbon contributing to climate change out of the air.

While the herd does not eat any pastureland down to bare soil, they do keep the grasses clipped closely enough that they never go to seed. To further prevent soil erosion, boost biodiversity, and attract more natural pollinators on their land, the Applebys are planting trees and hedge rows on the perimeter of their farm and have established significantly sized “pollinator patches” at four locations throughout their property, where wildflowers and grasses grow to their full propagating potential. On particularly overwhelming days, Sarah might disappear into one of the patches for some peace, but not necessarily quiet.

“You can lie down, hidden among the flowers, and listen to the buzzing of the insects and the sounds of the birds. They calm me tremendously because even if I can’t readily measure things like increased carbon sink, I can hear that all the hard work we’re doing to make the soil healthier is paying off,” she says.

BEST MILK, BEST CHEESE

A longer-term shift involves downsizing the herd in order to match it to the natural resources of the farm, and breeding cows that will turn the grass into the best milk for cheese. To do that, the Applebys had to address their cows’ genetics. Sarah maintains that the use of genetics and other technologies can coexist with—and, in fact, benefit—the process of artisan cheesemaking. “One eye on the vat,” she says. “Everything we do on the farm is aimed at making the best milk to produce the best cheese possible.”

Sarah and Paul inherited a herd of crossed Holstein Friesians, breeds that hail from northern German and Dutch provinces, respectively, and are lauded worldwide as strong mild producers. But this high-output mixed breed requires a high degree of calorie input to produce the milk required to satisfy Appleby’s cheese production cycles. The grazing plan alone could leave them hungry and hefty supplemental feed is an unsustainable financial and untenable environmental cost for the business.

The Applebys recently introduced to the herd VikingRed cows, whose size and shape are well suited for the rotational grazing scheme. And they will cross breed ensuing descendants with short-horned Montbéliarde cows, whose lifespans are long and whose milk is particularly good for cheesemaking due to its high protein levels.The Applebys have changed their calving pattern so that all are born outside, naturally, in standing hay fields. But they haven’t yet adopted a calf-at-foot practice. Most of the calves are separated from their mothers soon after being born, so all the milk can be used to make cheese. In a calf-at-foot operation, some of their mothers’ milk goes to the calves. Keeping calves at their mothers’ side in the pasture until they can be naturally weaned at about five months can reduce mortality rates of the offspring and help them grow more quickly. The suckling can also help protect cows against mastitis, one of the biggest disease risks facing dairy farming today.

“It’s about joining the dots,” Sarah says, referring to how she thinks about what the Applebys’ next regenerative farming steps might be, making sure any project fits into current processes in a symbiotic way. They’ve considered biomass heating and water harvesting systems, but both of those would require an overhaul of historically significant, listed buildings, which is a lengthy and expensive prospect. “And while calf-at-foot is certainly not off the table, we do know, from friends who are trying to do it in Scotland, that it is a very difficult way to run a dairy farm. And we don’t know how that process would affect our cheese,” she says.

When you’re the stewards of the last traditionally made Cheshire cheese of its type on the planet, everything you do has to be viewed through that sunset pink lens.

THE REIGN OF CHESHIRE CHEESE

Cheshire is a territorial British cheese, meaning it is named after the area where it has traditionally been produced. The Cheshire Plains in northwest England is a lowland region with salt beds left thousands of years ago by receding glaciers. The mineral-rich soil, ryegrass, and wild clover are all part of the terroir that give the cheese its unique character—a juicy minerality, moist and crumbly, with a subtle salty tang.

The mild climate and lush pastures of the Cheshire Plains meant more milk, and therefore cheaper cheese, which was shipped from Liverpool to London, by the ton, to be sold. Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese pub has stood at 145 Fleet Street in London since 1538—its name is a testament to the time when Cheshire cheese ruled the roost in Britain. At its peak in the 18th century, it was more popular than cheddar or Stilton. The distinct, sunset orange-pink color comes from annatto, a coloring derived from the seeds of the achiote tree, discovered in the Amazon, and originally added to distinguish Cheshire from other cheeses at the London market.

Other counties, keen to replicate the success of Cheshire and capitalize on the London markets’ appetite, began making cheese of a similar style. Lancashire, Double Gloucester, and Red Leicester were all spawned as a result of Cheshire’s popularity.

The popularity of Cheshire cheese steadily declined through the 20th century. In 1914, there were over 2,000 farms producing the cheese, but when Lance and Lucy Appleby took over Hawkstone Abbey Farm in 1952, the cheese was close to extinction due to an increase in less-expensive imports from the United States, a shift in diets, and a move from farm to factory food production.