Cheesemaking, a transformative art that necessitates a delicate balance, reminds us that not everything in life will turn out as we expect. The promise of a mozzarella’s sturdy stretch sometimes yields a rubbery snap; a luscious white fuzzy rind may be mottled with strangely hued molds; the smooth paste of your dreams can end up fractured and fissured.

Making good cheese is hard. So why not leave it to the experts? For some of us, homemade cheese fits within a broader philosophy of self-sufficiency. “It’s rewarding and satisfying to know you made or grew everything on the family dinner plate,” says Cypress Grove founder Mary Keehn, who started in the ’80s as a DIYer. For others, slowly mounting that steep learning curve becomes an obsession. “To love cheesemaking and be good at it, you have to love ongoing challenge,” says Gianaclis Caldwell, an Oregon-based cheesemaker and author who also grew her kitchen hobby into a full-fledged business at Pholia Farm. “The science and artistry of making cheese is an addictive and stimulating challenge.”

Here’s the good news: With a little patience and practice—and a lot of curiosity—anyone can make cheese at home using kitchen tools and a few basic ingredients. The key is to take it one step at a time. “Start simply,” Caldwell advises, “and build on your technique, knowledge, and expectations.” The first step? Peruse our guide for an intro to the process, the ingredients, and all the pro resources you should seek.

Get to Know Cheese’s Four Fundamental Components

Milk

At first glance, milk is a simple mix of liquid and solid components: mostly water, with suspended molecules of fat, protein, sugar (lactose), vitamins, and minerals floating around. But thanks to endless variations in animal breed, feed, season, and geographic location, milk’s quality and composition is fluctuating and complex. As the cheesemaker, your goal is to separate a large portion of the milk’s solids from its water, creating a more shelf-stable product that reflects and enhances the substance’s inherent qualities. To do that, you’ll add ingredients that encourage coagulation—the rearrangement of milk’s proteins into a firm network.

FAQ: If milk is so important, how do I pick the right kind? A few general guidelines: Use whole milk, as fat creates delicious flavor and texture (unless your particular recipe calls for skim and/or cream). Don’t use ultrapasteurized or homogenized milk, since those processes alter the way the essential solids behave. Using raw (unpasteurized) milk has many perks in terms of flavor and beneficial microbes, but if you want to work with it, take the time to learn a bit more about the critical role of animal health and milk hygiene—then find a provider you know and trust.

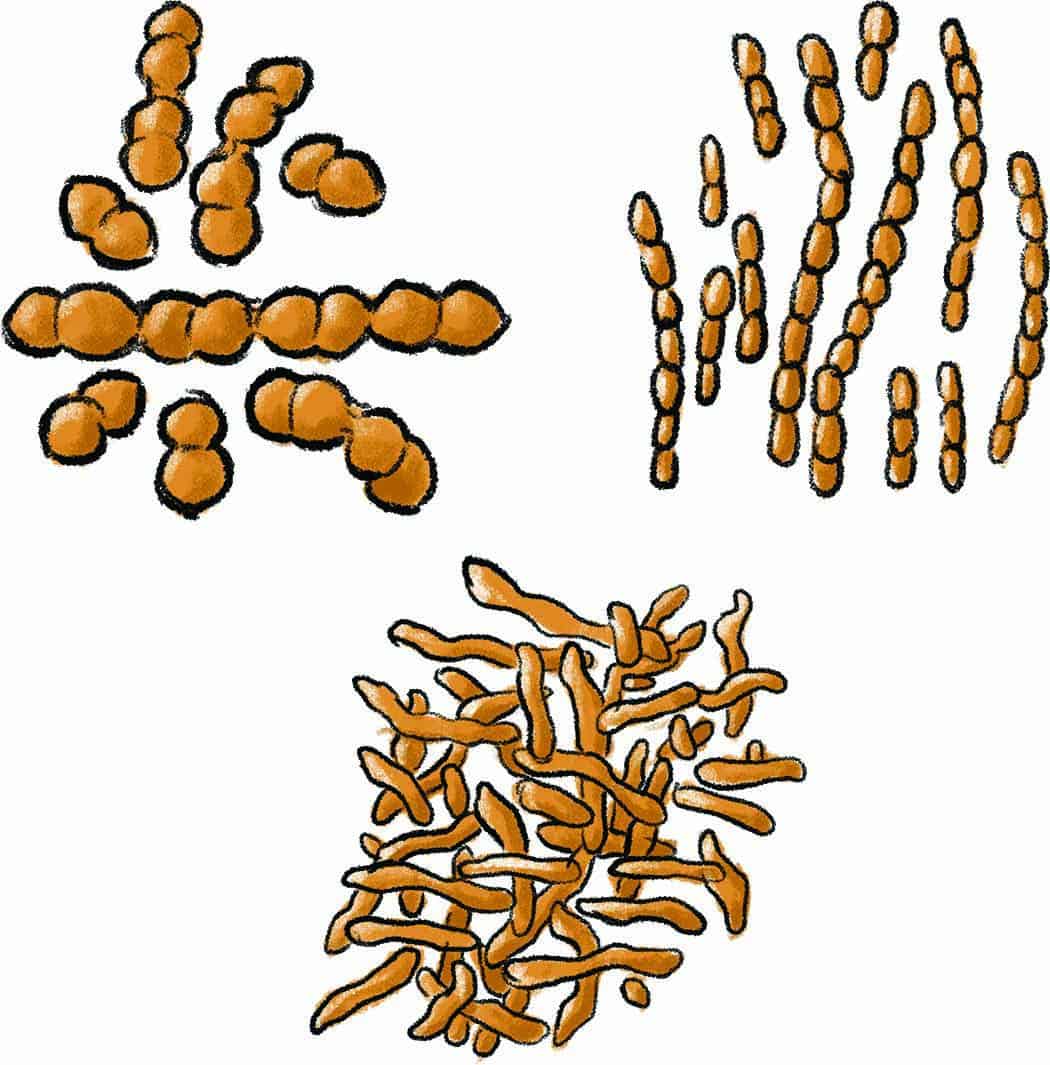

Cultures

Whether or not milk is pasteurized, microbes—bacteria, yeasts, and molds—are essential to the ever-evolving life of a cheese. The critters you use will depend on your recipe. Some play a role right away; for example, lactic acid bacteria immediately begin consuming milk sugars, converting them into acid that encourages coagulation. Others play a role much later, like blue mold spores: While they’re added early on, they start growing only when the cheese is aging. Depending on the recipe, microbes might also be added after the cheese is formed (either rubbed or sprayed on the outside of wheels).

FAQ: Wait—shopping for bacteria? Is that a thing? It sure is—and cheesemaking supply companies make it super easy. In most cases, a curated mix of cultures for a certain cheese style can be ordered online and will arrive freeze-dried in a packet. Remove what you need from the package using the tip of a knife, taking care not to get the cultures wet. Reseal the packet and store the remainder of the contents in the freezer.

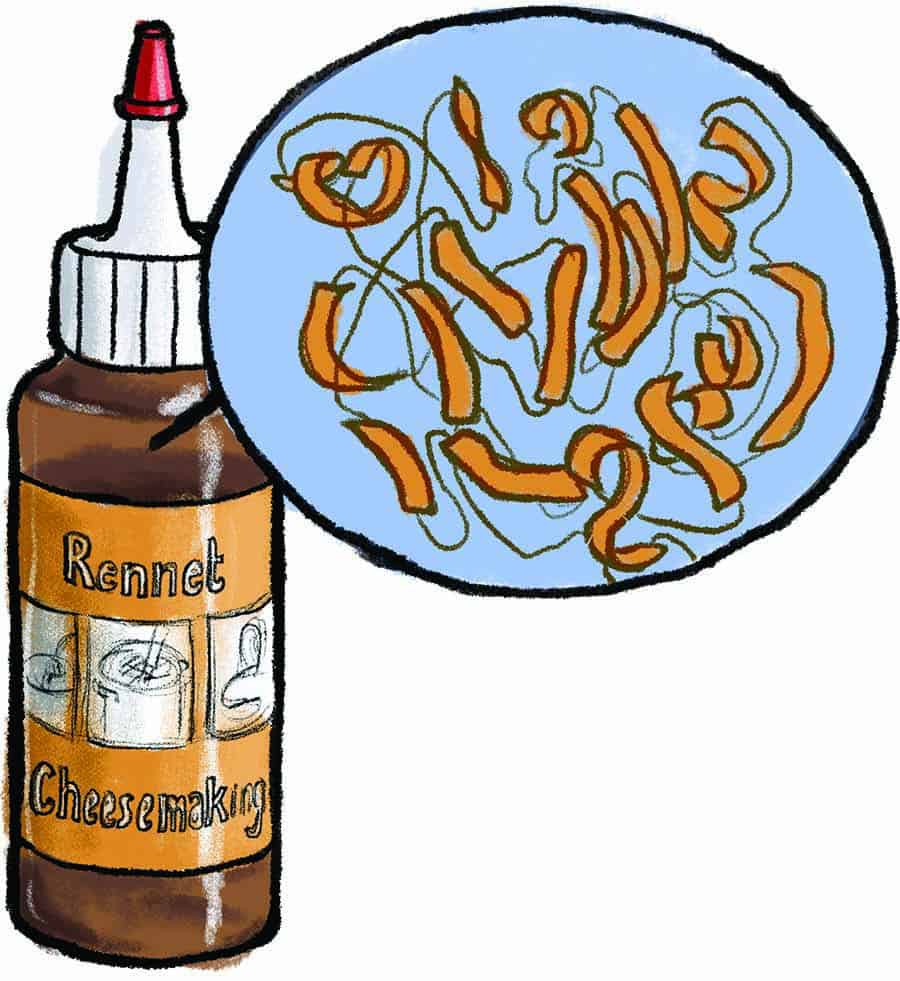

Rennet

Whether it’s sourced naturally from the stomach of a young cow, goat, or sheep; created in a lab; or derived from thistle flowers, the key ingredient in this concoction is an enzyme that works magic on certain proteins suspended in milk, allowing them to bond together into a gel-like network (the curd). Rennet can be ordered from a supply company in liquid or tablet form. You can choose between “traditional” rennet (from an animal’s stomach) or “microbial” rennet (a vegetarian version made in a lab)—but when it comes to beginner cheesemaking, the difference is subtle.

FAQ: Do I always need rennet to make cheese? While most cheeses in the world are made using rennet, this substance isn’t the only ingredient with the power to transform milk. Milk can also be coagulated using acid—you’ve seen this happen if you’ve ever added lemon juice or vinegar to milk. Some cheese recipes simply require a dose of citric acid or vinegar for a quick curdle. Others, such as delicate “lactic-set” fresh or mold-ripened cheeses, may rely solely on the acidification created by starter culture bacteria. But thanks to its ability to create a strong yet versatile curd, rennet reigns as the most common coagulant among cheesemakers.

Salt

Yes, it’s delicious. But in cheese, salt is more than a seasoning: It’s a preservative. It makes the cheese environment less hospitable to spoilage bacteria and jump-starts the formation of the rind. Additionally, by controlling the activity of microbes and enzymes, salt in turn influences the development of specific flavor compounds and textures.

FAQ: Can I use just any old salt? If you’ve made a fresh cheese and plan to eat it right away, using plain table salt is no problem. But if you’re planning to mature your cheese, avoid iodized varieties or salt with anti-caking agents, which will mess with your cultures. Instead, opt for kosher or sea salt. Also keep in mind how you’ll be adding salt, as it can be dumped directly into curds, rubbed on the outside of wheels, or used to create a brining solution depending on the recipe. A fine salt works best for brines, while flakes lend themselves better to an outside rub.

The Other Essential Ingredient: Time

A fresh cheese is one thing, but an aged cheese is much more complex. There’s a reason that some people devote their careers entirely to affinage, the art of maturation. Newly formed wheels are teeming with life, and as they age, microbes and enzymes from both within and outside break down sugars, fats, and proteins, a chaotic process that the affineur attempts to control using humidity, temperature, and care. When starting out, you can vacuum-seal fresh wheels inside a plastic bag for safe and easy aging, but to curate complex rinds and flavors, you might want to retrofit a fridge and turn it into an aging cave. Find out how at culturecheesemag.com/cheese-cave.

The Step-by-Step Basics for Most Cheese Recipes

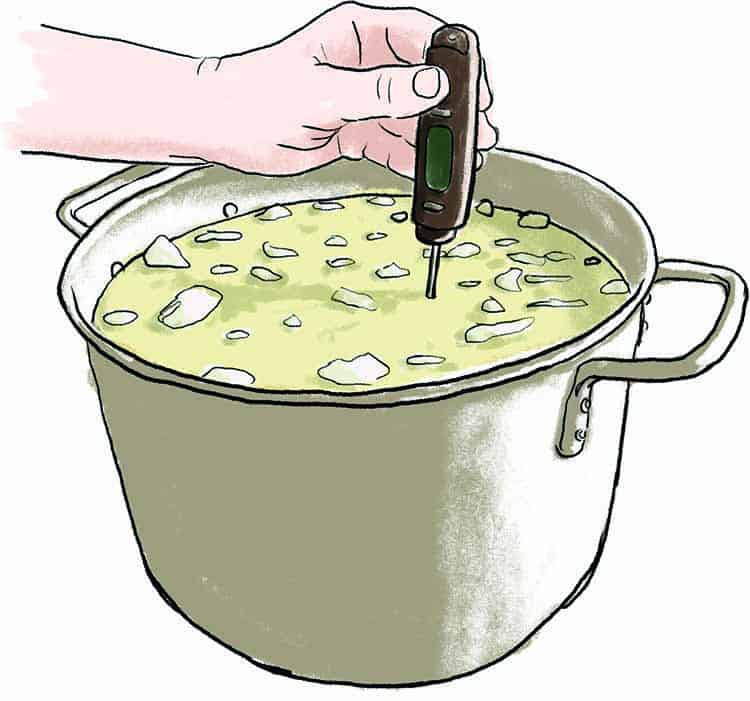

- Culture: Warm your milk to the right temperature, add the right mix of microbes, and let them do their thing. Use a stockpot on the stove.

- Coagulate: Add rennet or another curdling agent and wait until the milk turns into a gel-like network. Use a medicine dropper.

- Cut: Slice that firm network into morsels of the right size and shape. A long knife gets it done.

- Stir: Mix your curds to expel moisture and firm them up a bit. A slotted spoon does the trick.

- Heat: If you’re making a hard, aged cheese, you’ll cook the curds a bit to make them even sturdier. Bust out that kitchen thermometer.

- Drain: Remove the liquid whey from the solid curd by straining. You’ll need a colander and/or cheesecloth.

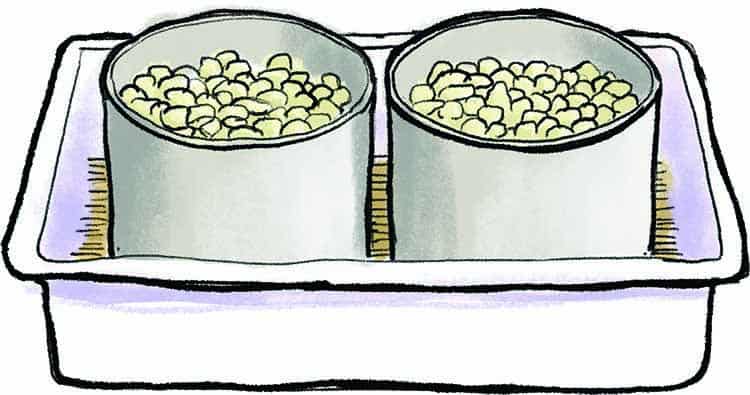

- Form and press: Add your curds to the right type of form and, if necessary, apply weight to expel more whey. Buy cheese forms from a supplier or repurpose plastic containers. You’ll also want to get a draining mat.

- Salt: If you haven’t already mixed it into the curd before molding, rub salt on the outside of the wheel or dunk your cheese into a brine solution. Use a plastic tub when brining.

- Age: Manipulate the development of your final product with the right blend of temperature, moisture, time, and TLC. A plastic storage bin works great for maturing cheese at home.

3 Cheesemaking DIYs to Try

Camembert

It took French makers centuries to perfect this bloomy-rind disk—but don’t let that intimidate you. Our recipe uses a mix of skim milk and heavy cream, plus rennet, calcium chloride, and a few cultures you can get easily from any cheesemaking supply company. Once you’ve conquered camembert, you can start experimenting with similar styles like brie and Saint André. Learn how to make it at culturecheesemag.com/diy-camembert.

Burrata

This recipe from Gianaclis Caldwell walks you through mozzarella and ricotta, blending the two Italian cheese styles to make a decadent ball of fresh burrata—and get this: It takes only an hour. Gear up with a gallon of milk, some rennet, citric acid, and a bit of butter before diving in, and be sure to skim Caldwell’s handy list of mozzarella tips and tricks to ensure that your pasta filata has all the stretch it needs: culturecheesemag.com/diy-burrata.

Blue Goat Cheese Log

Surprisingly, all you need to make an externally rinded blue chèvre is a mix of goat’s milk, buttermilk, rennet, salt, and some mold scraped off your favorite blue cheese. Louella Hill’s method makes it super simple: Milk is cultured and coagulated inside a plastic bottle over a day, then strained through a cheesecloth until it’s mixed with salt and formed into a log; the blue mold rind grows in about three days. Get the recipe at culturecheesemag.com/diy-blue-goat-cheese.

Looking Back: Mary Keehn

What began as a single mom and 4-H leader’s kitchen hobby evolved into an iconic California chèvre business: Cypress Grove, now in its 35th year of operation.

“Some of the cheeses we all want to start with—such as cheddar or soft-ripened cheeses—are very demanding in their need for a precise, slow temperature increase over a relatively long time during the make process, which is difficult. And once I’d made those cheeses, I sadly found that most home refrigerators do not have proper settings for successful ripening. So sad after a lot of work!

Early on, I was speaking with the very first reporter to do a story about Cypress Grove. I mentioned some of the early failures, and the fact that we also raised pigs who benefited greatly from my learning. The headline in the local paper (luckily a small readership) the next day was “Pig Slop to Gourmet Delight.” Luckily we don’t know what we don’t know, and there was so much I did not know! To this day I don’t know how the stars aligned to make it work.

My advice: Keep things clean, start at the beginning with some fresh cheeses, and get some pigs—you’ll want an outlet for those not-so-perfect efforts!”

Looking Back: Dan James

Not long after making their first batches of cheese in the kitchen, Becca and Dan James conceived a recipe for their first aged wheel: Belford. Seventeen years—and a new creamery, James Ranch Artisan Cheese—later, it remains their company flagship.

“Initially we bought one cow—Dolly. Sweet Dolly. I had never milked a cow or made cheese in my life, but she was very patient with me, and we milked her for a couple of years and made our cheese on the stovetop. We started with fresh cheeses—farmers’ cheeses—those are the easy ones.

But we’re firm believers in using raw milk, so while fresh cheeses were nice, we wanted to head in another direction, with aged cheeses. It’s a jump that you make—kind of like graduating high school and going to college, because now you need to control temperature and humidity while aging. They make great tools for that now, like a little apparatus you can put on a standard refrigerator and trick it into being a warmer temperature. But for me, it was finding somebody’s root cellar, putting cheeses in Tupperware tubs, and stuff like that. I tweaked the recipe here and there—you could call it luck, but I think to be successful in cheesemaking you need a certain personality, an attention to detail.”

Looking Back: Sheila Flanagan

This former lawyer and her partner, Lorraine Lambiase, started with four Nigerian dwarf goats on a one-third-acre parcel in Oakland, Calif. After making cheese for six months, the duo decided to go all in and founded Nettle Meadow Farm; their cheeses have since won countless awards.

“We were really new to the whole process. We went, ‘Wow this is really great, we are just the best cheesemakers in the world, we should do it for a living.’ But it was very basic cheesemaking—looking back I kind of laugh, because we were so naive back then, but we jumped in with both feet.

You can do so many different things with homemade cheese. If you’re making cheese with only two gallons of milk, you can mix it with high-end ingredients that you find at your local specialty store, add herbs, fruits, flowers—you can do amazing stuff. Making cheese in your kitchen is such a fun experience, and it’s fun to dream about making a career out of it. But when you extrapolate it into a business, it becomes much harder; the economic situation doesn’t allow for as much experimentation as you can do in your home. I’m thrilled we jumped in, but there are luxuries of home cheesemaking that I miss—I’d love to be able to go back for a week and do whatever I wanted with whatever ingredients I might be able to find.”

Required Reading

Snag one of these reference guides to ease into expertise

- Mastering Basic Cheesemaking (New Society Publishers, 2016) is a comprehensive intro from Gianaclis Caldwell, whose love for the “seductive and satisfying craft” flows across the pages as she explains cheesemaking science, delves into essential tools, and details recipes of varying complexity. (Once you’ve mastered these recipes, graduate to Mastering Artisan Cheesemaking, Caldwell’s more advanced guide.)

- When first starting out, many pro makers—including Mary Keehn of Cypress Grove—turned to the classic reference Cheesemaking Made Easy, first published in 1981 and revised in 2002 as Home Cheesemaking (Storey Publishing). Authors Ricki and Robert Carroll don’t just write about homemade cheese: They’ve also helped countless DIYers with gear via New England Cheesemaking Supply, which they founded in 1978.

- Elena Santogade, who started her career in the cheese industry by making and aging wheels in her Brooklyn kitchen, passes on the wisdom she’s accumulated over time in The Beginner’s Guide to Cheesemaking (Rockridge Press, March 2017). Her inspiring guide offers handy troubleshooting advice, tutorials, and Q&As with pro makers.

- After teaching cheesemaking classes in San Francisco for years, Louella Hill, aka the Milk Maid, decided to channel her know-how into a book, Kitchen Creamery (Chronicle Books, April 2015). We love the way Hill uses handy charts and illustrations to demystify complex concepts in this approachable book.

- With her book Artisan Cheese Making at Home (Ten Speed Press, August 2011), cooking instructor and author Mary Karlin will keep any new DIYer busy. Not only does she detail how to make 100 types of cheese, but she offers recipes for cooking with the homemade creations, too.

- Claudia Lucero, founder of cheese kit company Urban Cheese Craft, keeps it simple and fun in One-Hour Cheese (Workman Publishing, May 2014). The guide zooms in on 16 quick and easy cheese styles while offering a range of customization options, many incorporating creative flavor combos.

I need cheese culture and ingredients

I Would totally endorse all you have said about cheese making, i describe it as mud pies without the worms! Very tactile and so therapeutic.

I would also like to recommend Paul Thomas’s book, “Home-made Cheese” published by Lorenz books. ISBN 978-0-7548-3242-3. It is sub-titled “Artisan cheesemaking made simple”

Thanks for the recommendation, Roger!