Cheese tales: They develop over centuries in famous dairy regions, giving meaning to food and situating it in space and time. In Wisconsin, such stories tend to begin with settlers from European nations such as Switzerland, Germany, or Italy, who brought cheesemaking traditions with them. If Brie evokes Charlemagne and Alpine cheeses conjure a yodeling shepherd, Wisconsin cheeses recall one of these immigrants, the keeper of ancestral secrets for turning cow’s milk into beloved Badger State wheels.

During a weeklong visit to America’s Dairyland, I couldn’t help but notice signs of cheese lore everywhere: bovines, burly fourth-generation farmers, Swiss flags, family crests. In fact, I thought I had the state’s cheese scene all figured out—until I pulled up to LaClare Farms in Malone, on the shores of Lake Winnebago. Immediately, something was different. First I saw goats. Then I saw Katie Fuhrmann.

Attendees at the 2011 United States Championship Cheese Contest must have felt similarly when they saw her—a petite woman of no more than 25 with just a year of cheesemaking experience under her belt—take home the US Champion award for her goat’s milk gouda-style Evalon, besting 1,601 other cheeses from around the country. Not only was Fuhrmann, née Hedrich, the youngest cheesemaker ever to win the prize in the contest’s 120-year history, she was also the second woman. While prizewinners are a dime a dozen in Wisconsin, cheesemaking women are a rare breed, accounting for less than five percent of licensed makers in the state.

Prologue

Unlike so many of her male peers, Fuhrmann’s cheese story does not begin with a lederhosen-donning, cow-herding great-grandfather. Instead it starts in 1970s Wisconsin, with her parents, Larry and Clara Hedrich: newlyweds with a small backyard and two goats named Whiskey and Brandy.

The Hedrichs always dreamed of making cheese from their goats’ milk. “We went to goat farms on our honeymoon,” Larry remembers. “We visited cheese plants from day one, and we wondered, How can we make this work?” At that time nearly all Wisconsin cheese was made with cow’s milk—the market for chèvre simply didn’t exist—so the couple kept their day jobs (Larry in construction, Clara as an agricultural science teacher) while raising five children and a small herd of 4-H show goats.

When a few goat cheeses arrived on the scene in the 1990s, the Hedrichs finally found a place to sell their milk: a cheese plant 25 miles away. In 2005, Larry and a handful of other goat farmers formed the Quality Dairy Goat Producers Co-op to collectively sell goat’s milk to other cheese plants around the state. But it wasn’t until 2008 that the Hedrichs developed their first cheese, teaming up with dairy consultant Neville McNaughton to create a recipe and using the vat at nearby Saxon Creamery.

The herd hangs out at LaClare Farms.

Chapter One

That cheese—Evalon—was good. So good, in fact, that the first time the couple entered it into the US Championship Cheese Contest (in 2009), it placed second in its class. Larry and Clara were unable to attend the awards ceremony, so they sent their daughter, Katie, instead. At that time, she’d just graduated from Northern Michigan University with a degree in marketing, and was working as a retail manager at Target. “I was hating my life,” she says.

Fuhrmann recalls that night vividly. “I was sitting in the hallway awkwardly before the reception, because I didn’t know anybody.” But alone and quiet, she was listening—to cheese industry friends, to the Master Cheesemaker and his wife seated next to her during the reception—and she was fascinated. “It was just neat,” she remembers, “the connections that people had … it wasn’t even so much about the cheesemaking. It was more about the community, about how cheesemaking impacted families. I was just thinking: This is what I’m missing.”

After the awards ceremony, Fuhrmann called her father with a sweeping proclamation: “I’m going to be a Master Cheesemaker.”

Larry didn’t take her seriously. “I was like, OK, whatever, I gotta milk,” he says. Later, his efforts to dissuade her were in vain. After volunteering at Saxon Creamery for two days, Fuhrmann finalized her decision. It wasn’t long before she took over Evalon’s production at Saxon, and she has worked and experimented tirelessly to expand the business ever since.

Having found her calling, “the rest was history,” she says.

Making raw goat’s milk cheddar

The Plot Thickens

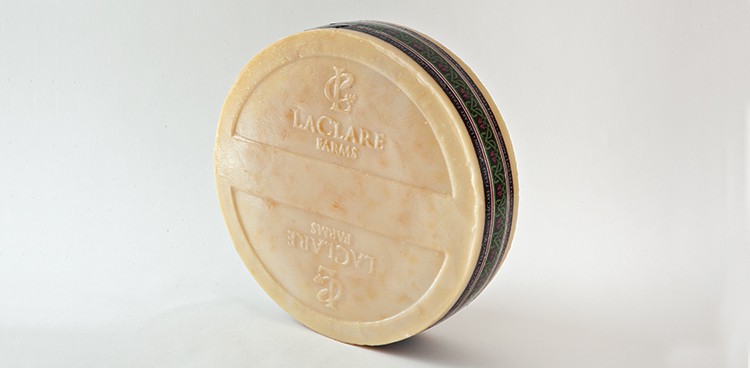

Today LaClare Farms makes 20 to 30 variations on five different cheeses, in a sparkling new plant the Hedrichs opened in 2013. Some, like Evalon, are crafted with raw milk from the LaClare goatherd, while others—such as fruity, cheddar-like Chandoka—have pasteurized cow’s milk in the mix. (Some wheels of Chandoka are sent to aging caves at Standard Market outside of Chicago, where they’re bound in cloth and aged for up to two years.) The awards keep coming: Evalon won first in its class at the 2012 American Cheese Society Judging & Competition, while cave-aged Chandoka won runner-up for Best of Show there in 2015.

Cheddar-style goat’s and cow’s milk Chandoka

The company released a line of goat’s milk yogurts in June and plans to begin processing whey next year. The new facility—which includes a farm, creamery, aging cave, retail shop, and café—employs 20 locals, including three more of Larry and Clara’s children: Greg is the business manager; Anna, the herd manager; and Jessica runs the retail shop and café.

The return of the family has been a lucky surprise. “You can’t pound a square peg into a round hole,” says Larry, who never intended to mold his children into farmers. “My children had to go out and find their passions. But they learned skills that we needed for this business, and brought those back to us. That was good fortune.”

It’s all the more remarkable given the struggles faced by family farms today. Despite a thriving cheese industry, 20,000 acres of farmland are lost in Wisconsin each year, while the average age of a farmer is 57. Small farms face pressure to increase their size, and more than 50 percent of farmers hold off-farm jobs.

LaClare Farms goats in the barn attached to the family’s new creamery in Malone.

The Story Continues…

Fuhrmann believes that goats have promise. “In my opinion, goat farming is the new family farming,” she says. After all, goat farmers can increase herd size without needing the same infrastructure as they might with dairy cows, while benefiting from a growing milk market. If goats represent opportunity in Wisconsin, it’s likely in part because the Hedrichs have pursued their dreams with the wider community in mind. Today Larry is president of the Quality Dairy Goat Producers Co-op; at least two new family farms will join the organization this year.

Having apprenticed alongside many Wisconsin Master Cheesemakers and en route to becoming one herself, Furhmann understands the value of cooperation. “Good cheesemakers breed other good cheesemakers, and people collaborate and make the area better for everybody,” she says. LaClare’s store sells cheeses from other local producers, as well as goods from the region.

LaClare has grown to an extent that nobody imagined possible. “It’s not like a lot of other businesses, where it’s like, let’s see if this works,” Larry says. “We have to make it work. We don’t have any other options. We are all in.”

If there’s one thing the LaClare story shares with that of Wisconsin cheese, it’s the idea of passing down traditions to the next generation. The land on which the Hedrichs opened their new farm once belonged to Larry’s grandfather, and today Larry and Clara’s grandkids scuttle around it, chasing goats. Theirs isn’t a story that began in Europe. It’s homegrown, a new kind of Dairyland cheese legend that’s still unfolding—with the Hedrich family at the helm.

The Hedrich family members who work at LaClare Farms, from left to right: Katie Furhmann, Greg Hedrich, Anna Zastrow, Larry Hedrich, Jessica Mayer, and Clara Hedrich.

Photography by Chris Homayouni