Written by Culture Staff

You can’t have artisan cheese without art…

Sounds like something you’d see on a motivational poster. But if art is about creating beauty, at the heart of artisan cheesemaking is a desire to create something beautiful and delicious. Time, patience, practice, money, and a whole lot of elbow grease are the foundations of every artisan cheese recipe, but what lies at the root of the craft is creativity.

Artisan cheese differs from commercially produced curds in myriad ways, but the most visible to the consumer may be the cost. Why, when a block of sharp cheddar can be had at the grocery store for under five dollars, does the same amount go for well over 30 dollars per pound at the independent cheese shop? The answer starts with the human hand.

The American Cheese Society defines artisan cheese as being produced primarily by hand, from the highest-quality ingredients, with as little mechanization as possible. Artisan makers will often look to traditional, non-mechanized methods of milking, molding, and aging cheese, which adds to the time and people power needed to turn out a single wheel. And like any dedicated artist, artisan cheesemakers are willing to take the long route to perfection in the name of their craft—the payoff being a unique, aesthetically striking, and nuanced product, worth the effort a hundredfold.

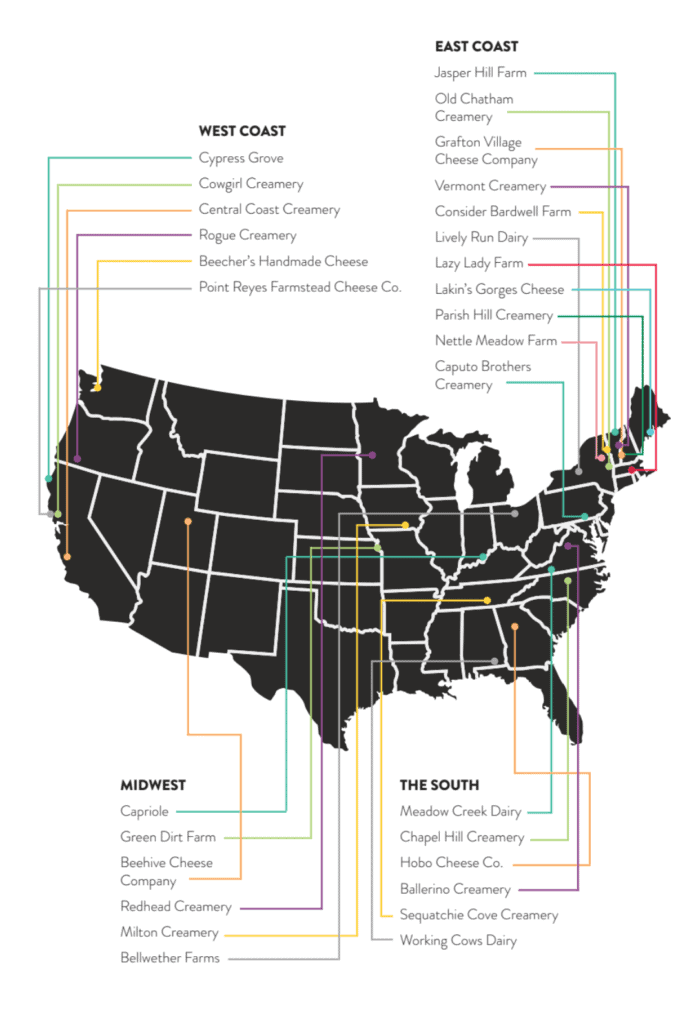

WHERE IN THE WORLD?

Sure, we’ve all got our favorite local makers, but do you know about the artisan cheese efforts happening elsewhere? (Please note that this is not an exhaustive list.)

LIFE CYCLE OF CHEESE

“For us, the cheese is artisan because of the people who make it. Our cheesemakers carefully handle every cheese we make. Those cheeses are hooped and salted, turned daily, and lovingly packaged for our consumers, all by hand. During each step of the process the makers meticulously inspect each wheel and evaluate and cater to whatever its needs are, using the knowledge gained here and elsewhere to guide their decisions. The term artisan should be applied to anyone who cares deeply and personally for the product they make.” —ERIC GLASGOW, co-owner, The Grey Barn and Farm, Chilmark, Massachusetts

ANDY HATCH AND SCOTT MERICKA, UPLANDS CHEESE COMPANY

In the rolling hills of southern Wisconsin, Uplands Cheese Company is located in the heart of a rich and storied American cheesemaking region. But the dairy farming practices that produce Uplands’ award-winning cheeses originated hundreds of miles away in Vermont, where rotational grazing to feed cows was introduced in the late 1980s. The founders of Uplands Cheese were among the first farmers in the country to adopt the practice to feed their dairy herd. These cheesemaking pioneers turned the raw, grass-fed milk into traditional, Alpine-style hard cheeses, the precursors of today’s Pleasant Ridge Reserve—the most-awarded cheese in American history.

Uplands’ current owners, the creators of Pleasant Ridge Reserve, came to work at the farm after studying dairy farming and cheesemaking—Andy Hatch at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Scott Mericka at Warren Wilson College in Asheville, North Carolina. The two men, along with their families, purchased Uplands Cheese in 2014; Mericka oversees the barn, while Hatch runs the creamery, which turns out just two cheeses. Crafted in the tradition of Gruyère and Beaufort, Pleasant Ridge Reserve is made only from May through October; and Rush Creek Reserve, a rich, soft round wrapped in spruce bark, is made only in the fall. “We walk the tightrope of a truly seasonal business, trying to balance inventory in one hand and cash in the other,” says Hatch. “We gamble about a million dollars every summer, making cheese and tucking it away until it becomes next year’s income. It makes for a very hardworking summer, and if things have gone well, a very content winter.”

A Wisconsin native who didn’t grow up in the dairy business, Hatch remains closely connected to the people and resources of the University of Wisconsin’s College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, especially the Center for Dairy Research, which he calls “a national treasure.” The location of the farm, relatively close to Madison, the state capital, gives him access to the political side of the state’s diary industry. “We’re a very small producer, but we have a seat at the table when we need to learn something or make our thoughts known,” says Hatch. “People in Wisconsin’s dairy industry tend to be very cooperative and generous, and no one excludes us from the conversation because we pasture our cows and use raw milk and natural rinds. Most of the old guys grew up that way and respect it.”

Artisanal cheesemakers all over the country cite the importance of being connected to a community, and Hatch and Mericka are no exception. Many cheesemaking operations are in remote, rural areas, so having neighbors—even if they are not right next door—who also farm and make cheese “makes a world of difference, both for finding new solutions to business problems and for feeling supported in the midst of what can be some pretty difficult circumstances,” says Hatch. “Just drinking beer at a bar next to a guy who also blew his whole afternoon trying to fix a frozen manure spreader…it feels less isolating.” Uplands shares equipment and harvest work with a few farmers nearby and consolidates pallet shipments with a couple of other local cheesemakers. “It helps keep everyone’s costs down,” he says.

Hatch makes artisan cheeses prized by turophiles, but in keeping with his midwestern roots, he takes a pragmatic, rather than esoteric and worshipful approach to the farm-to-table, “slow foods” agriculture movement. “There are some very important economic and ecological reasons to support sustainable agriculture but I think the proof also has to be in the pudding,” he says. “It may be that the more destructive elements of modern agriculture will eventually be eliminated by regulation, but if that leaves us with foods that are equally responsible and boring, no one is going to be inspired and it will wither.” Ultimately, he says, “farming and food have to be responsible but they should also be joyful. I think that’s why grazing dairy cattle is so important. It’s better for the climate and for the soil, water and animals, but it also produces really sublime cheese. It’s a win-win-win.”

“What thrills me to no end is working with other cheesemakers and encouraging people to go backwards. To really look to traditional methods, look at what they were doing, look at the resources they had in hand, and really try and make the most of those. I feel like what is the next step for American cheesemakers is to stop trying to make cheese that other people make. Really looking at what is unique and special about their particular milk and their particular situation, and what does their milk do best, instead of trying to wrangle it into being something it’s not. To see what it is in and of itself.” —RACHEL FRITZ SCHAAL, co-owner, Parish Hill Creamery, Westminster West, Vermont

JESSICA AND JEREMY LITTLE, SWEET GRASS DAIRY

At Sweet Grass Dairy in historic Thomasville, Georgia, Jessica and Jeremy Little’s Jersey cows graze on grass 365 days a year. The herd’s rich milk is made into award-winning artisan cheeses, including double cream, Camembert-style Green Hill; earthy yet mild Asher Blue; and semi-soft, natural-rinded Thomasville Tomme—the very first cheese the creamery produced in 2002. “We hired a French cheesemaker to come to Georgia for two months to teach us more about cheesemaking,” says Jessica. “He is from the Pyrenees mountain region—where tomme-style cheeses originated—so it was a good place to start.” The second cheese added to the roster was Green Hill, which has become Sweet Grass Dairy’s flagship cheese. “It is such a good representation of our rich, buttery, grassy, and mushroomy milk,” she says.

The seeds of Sweet Grass Dairy were planted in 1993, when Jessica’s parents—her dad is a fourth-generation dairy farmer—switched their conventional dairy operation to a rotational grazing model. “Almost immediately, my mom wanted to tell the story of the high quality and flavor of the milk combined with the health and longevity of the cows,” says Jessica. Cheesemaking became the family’s storytelling platform, conveying the message of “humane animal husbandry, regenerative agriculture, and the importance of understanding the origins of our foodstuffs.” Jessica and Jeremy, who had met at college, were invited to join the business in 2002 and purchase the creamery three years later. “We have been trying to make an impact on our community region, and industry since then,” Jessica says.

In the early days, Sweet Grass didn’t have much competition. While agriculture has a long history in theSouth, cheesemaking is a more recent development there than in other parts of the country; prior to refrigeration, there wasn’t a way to keep cheeses cold during the aging process. “It has been such a fun journey to watch the rise of the farm-to-table movement in the South,” says Jessica. Along the way, the Littles have traveled across the country to visit other cheesemakers, “learning about blue cheese at Point Reyes, looking at soft-ripened aging-cooler design at Vermont Creamery, talking about wooden shelving with Brian Fiscalini at Fiscalini Farms, getting a deeper understanding of the science of cheesemaking at Jasper Hill, and learning about the importance of affinage at Uplands.” Having experienced the support and mentorship of the cheesemaking community, she and Jeremy feel it is now their duty to help fledgling cheesemakers in their region.

As part of that effort, the Littles are members of the Southern Cheese Guild, with which Jessica’s mother had been involved in its early days. The first group eventually disbanded, but reorganized in 2018 and is now a vibrant nonprofit organization. “Through outreach and education, we help cheesemakers and their cheese stories to ‘spread,’” says Jessica. “I think that it is hard for rural cheesemakers when we are so faraway from major cities to interact with customers. We need cheesemongers to tell our stories and what makes each artisan cheese so special. We do not have large marketing and public relations budgets so we depend on the grassroots word of mouth. We work really hard to have strong distribution partner relationships and will continue to work on fostering friendships with our retailer partners as well.” The Littles also connect directly to consumers right in downtown Thomasville, where their popular cheese shop and restaurant is part of a supportive community of artisans and makers. “The shop gives us the opportunity to try out new projects and get great feedback,” says Jessica. Asked to name her favorite Sweet Grass Dairy cheese, she says it’s like asking her to choose a favorite child, but she admits that she especially loves Green Hill because of her fondness for soft-ripened cheese. For Jeremy, who “loves all blue cheeses so much,” it’s Asher Blue. “We probably eat more Thomasville Tomme than anything because of its versatility,” Jessica continues. “Our kids make quesadillas, grilled cheese sandwiches and mac and cheese with it.”

Next up for Sweet Grass Dairy is the completion of a new cheese plant, which the Littles and their team expect to occupy this fall. The project was delayed due to the pandemic, but Jessica maintains that the challenges posed by the coronavirus have actually been beneficial. “I think we will be a better business when this is all over,” she says. “We are looking forward to a robust research and development program and the ability to make more handcrafted cheeses safely and consistently.”

“Success for the American artisan cheese producer is determined almost entirely by his or her ability to make a cheese that is uniquely delicious and premium, and therefore differentiates itself from others within the marketplace. Creating a cheese that possesses complex, unique, and memorable flavors—often representative of a geographical locale—is the main goal. Achieving these qualities often means getting back to the basics of cheesemaking, which realistically translates into removing much of the mechanization process and investing heavily in milk quality, skilled labor, and other production costs.” —KATE ARDING, culture co-founder, cheesemaking consultant, and co-owner of Talbott & Arding Cheese and Provisions, Hudson, New York

STEVE BURGER AND SARAH WIEDERKEHR, WINTER HILL FARM

Close in miles but a world away in ethos from downtown Freeport’s sprawling L.L.Bean campus, Winter Hill Farm covers 55 acres of permanently preserved Maine farmland. Its current stewards are Steve Burger and Sarah Wiederkehr, who continue a cheesemaking tradition established in 2004 by a pair of retired teachers who then owned the farm. In the rolling pastures below the hilltop barns and farmhouse where Burger and Wiederkehr live with their two children, rare Randall cattle graze alongside Jersey cows; their milk goes into bottled, unpasteurized whole milk and yogurt, as well as nine different cheeses, two of which have won American Cheese Society awards. Burger manages the cows while Wiederkehr is the cheesemaker, although that wasn’t her plan when the couple moved from California to Maine to run Winter Hill Farm in 2011. “She will swear up and down that she never intended to be a cheesemaker,” says Burger. “I wish she would stop referring to herself as a reluctant amateur and admit that she’s really good at this.”

In California, where they lived on a small farm focused on education, Burger milked a few Jersey cows and Oberhasli goats, and Wiederkehr taught courses in food systems and agroecology at Stanford University, experimenting with cheesemaking in the farmhouse kitchen as time allowed. “When the opportunity to take over operations at Winter Hill Farm arose, I thought moving to Maine to milk cows and operate a small farmstead creamery seemed like a perfect idea,” says Burger. “Sarah was dubious, but I somehow convinced her that her home-scale skills would translate easily.”

An established revenue stream from bottled milk and yogurt sales allowed Winter Hill Farm to flourish while Wiederkehr developed cheese recipes, combining her skills as a trained scientist with the intuition she says still guide her process. Bringing pigs onto the farm proved to be fortuitous. “Our Berkshire pork quickly gained a reputation as some of the tastiest pork available—our secret was the volume of cheese failures our pigs regularly dined on,” says Burger. “I like to say: ‘Bad cheese equals good porkchops.’” Winter Hill Farm’s first two cheeses were Frost Gully and Tide Line, both Camembert-style rounds made from the same basic recipe. Tide Line differs in that it features a layer of vegetable ash running through the center and covering the cheese. Next came two aged raw milk cheeses with natural rinds: Everett’s Tome, a tomme-style cheese deliberately misspelled as a tribute to Everett Randall, the “father” of Randall cattle; and Bradbury Mountain Blue, the cheese of which Wiederkehr is most proud.“Bradbury was the most challenging cheese to develop—it took two years for me to get it to the point that I was consistently happy with it,” she says. “It has never won an award, but the feedback we’ve gotten from our customers, from cheese mongers, and from competition judges means so much to me. When someone tells you it’s the best blue they’ve ever tasted, you feel like you’re doing something right.”

Photo by Greta Rybus

While Wiederkehr made cheeses, Burger focused on increasing milk production through herd and pasture improvements. But by 2018, demand for the cheeses outpaced the farm’s milk supply. “Rather than expand our own herd, we were fortunate to be able to begin purchasing milk from the Milkhouse in Monmouth, Maine,”says Burger. “Their organic Jersey herd is managed very similarly to the Winter Hill herd, which translates to milk that blends seamlessly in our cheesemaking; 25 percent of the milk we use in cheese production comes from the Milkhouse.”

Burger touts Maine’s active cheesemaking community, which comprises close to 100 licensed creameries scattered about the largely rural state. “People in Maine are willing to support their neighbors and want to participate in a local economy—that lends itself to a thriving local food scene,” he says. “There are world-class cheeses being made here produced on such a small scale that no one from outside the state even knows they exist.” After the pandemic halted sales to restaurants, he and Wiederkehr partnered with other farmers, bakers, and makers to stock a self-serve farm stand, and turned down the temperature in their caves to slow the aging process of the wheels. “At the same time we realized that people wanted milk and yogurt—so much yogurt,” Burger says. “We could barely keep up.”

In addition to top-notch artisan cheese, Maine also has the nation’s highest number of breweries per capita, and collaborations between brewers and other makers are common. Winter Hill Farm regular partners with Maine Beer Company of Freeport, which offered the cheeses alongside their beers for pandemic pickup. A Valentine’s Day pairing with Portland’s Foundation Brewing featured Frost Gully with a raspberry kettle sour, a pairing Burger compares to “your favorite bread right out of the oven slathered in butter and raspberry jam.” Asked by Allagash Brewing Company in Portland to make a beer-washed cheese the brewery could sell in their tasting room, Wiederkehr came up with what remains her husband’s favorite cheese: Terzetto, a pasteurized round washed with Allagash Tripel and aged six weeks. “Have you ever walked into a tasting room expecting to smell beer and smelled the joyous funk of dirty feet instead? It was a problem,” says Burger. “The original was a much softer, ooey-gooey, eat-it-with-a-spoon little round that was pure unctuous joy—and it stank to high heaven. It was a hit at Allagash, but after a few months we changed the recipe—larger mold format, longer age—both of which robbed it of some of its joyous aroma and made it an acceptable guest in the tasting room.” He’s still hoping that someday Wiederkehr will bring the stinky original back. Perhaps it could include a warning label: Best enjoyed in Maine’s great outdoors.

WHY IS ARTISAN CHEESE SO EXPENSIVE?

Data is based on a 75-cow dairy farm model designed in 2011 by the University of Missouri, and a 2013 study published in the Journal of Dairy Science on the yearly cost of cheese production totaling 60,000 pounds.

1. Dairy farm operations (veterinary bills, feed, staff, quality tests, utilities, transport): $140,000/year

2. High-quality milk cost (if purchasing from second party): $12,000/year

3. Cheese production (utilities, lab tests, sanitation, payroll): $600,000/year

4. Other costs: packaging, transport

TOTAL ESTIMATED YEARLY COST: $800,000

Cheese produced at this facility would need to sell wholesale at $13/pound just for the makers to break even. Retail markups are often 100 percent.

SIDE PROJECTS

For many artisan cheesemakers, byproducts are a crucial way to make additional income and keep their creameries afloat. Makers across the country have gotten creative in this realm, embracing nuanced ways to reimagine their dairy animals’ products—sometimes from the confines of their own kitchens—and provide customers with goods that are farm fresh, artisan, and unique. Everything from sheep’s milk soap to goat’s milk caramels have helped boost independent creamery sales and kept these businesses going—even when faced with the staggering effects of COVID-19. And each product’s creation story is unique, coming from a place of passion and creativity.

WOOL

Brad and Meg Gregory of Black Sheep Creamery in Washington had no plans to become cheesemakers—they started milking sheep in 2001 when they realized the milk was better suited for their son, who was suffering eczema breakouts from cow’s milk. Eventually, they decided to start making cheese with the leftover milk. Then cheese production from milk turned into yarn production from wool, which has broadened their customer base to a wider demographic. “We’ve cultivated a following at fiber festival events,” Meg says. “People camp there and have their wine and cheese pairings after along day of festivaling.”

SOAPS AND LOTIONS

Colleen and Michael Histon of Shepherds Manor Creamery in Maryland started making soaps after realizing some of their sheep’s milk was going to waste. “When you run the milk through the pipeline, there’s about a half-gallon of milk that doesn’t go through the filter system,” Colleen explains. “So even if I wanted to take it and use it to make cheese, I can’t.” She decided to use that leftover milk to make batches of soap—3,500 a year to be exact, all from their own kitchen.

Using milk to make lotion has countless skincare benefits. Sheep’s milk has twice as much fat content than goat’s orc ow’s milks, and mixing that with olive, coconut, and palm oils—as in Colleen’s recipe—results in soap that makes hands consistently soft (no lotion needed). Goat’s milk soaps and lotions, such as those from Jollity Farm in California, have their own benefits as well: They’re rich in fatty acids, vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients that leave skin feeling moisturized, and can even prevent acne. It’s no surprise that the farm’s owners, MaryLisa and Charley Cornell, reported an increase in their soap and lotion sales during the COVID-19 pandemic, when people started furiously washing their hands and looking to support small businesses.

VODKA

Looking Glass Creamery in North Carolina had already seen success using cow’s milk to make their creamy Dulce de Leche sauce, Carmoolita, alongside their cheese selection. Now they’re planning on expanding their product line with some byproduct-based booze. “The idea has been rolling around in the back of my head for years,” says owner Jennifer Perkins. “But COVID brought it to the forefront.” After having to dump so much of their milk due to a drop in sales, Jennifer reached out to a former coworker at Oak and Grist Distilling to collaborate on milk fermentation to make vodka,“or Cowcohol, as we’re calling it in-house,” Jennifer says. The team has plans to start working on this product in the coming months.

CARAMELS

Using fresh milk in caramel is a no-brainer, which is why it’s caught on at multiple creameries. Louisa Conrad and Lucas Farrell of Big Picture Farm in Vermont started producing goat’s milk caramels with cheeses as a way to stand out as a company 10 years ago.“It was kind of a daunting competitive landscape,” she says. “We wanted to do something a little different.” Now, she swears by the use of goat’s milk in the production of the candy, explaining that since the milk components have shorter fatty acid chains, the act of caramelization results in a velvety texture that’s less grainy that cow’s milk caramel. But when asked which dairy product Louisa prefers making, she can’t help herself. “Cheesemaking is so sexy, it’s such a beautiful pure product,” she says. “And so I think you can’t really compete with that.”