This is the second in a blog series about Raw-Milk Cheese. This section focuses on the science behind the benefits of consuming cheese made from unpasteurized milk. Missed last week’s post on the health risks of consuming cheese made from unpasteurized milk? Check it out!

As discussed in last week’s post, raw-milk cheese looks like it’s relatively safe to eat, although not definitively so. But that’s only half the equation. Forget why I wouldn’t want to eat it—what about all those reasons I hear from my home-schooling cousin about why I should eat it? Well, I don’t know about how sleek and voluminous it will make your hair, but there is plenty reason to want to eat raw-milk cheese.

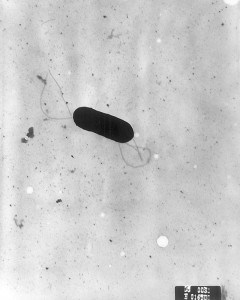

The first thing any advocate will point out is the native microbiota in raw-milk cheese. This is the thriving community of harmless organisms that is a casualty of pasteurization. Included amongst them are some anti-pathogenic agents. Though some journal articles are quite snarky about this point (“Unpasteurized milk. The hazards of a health fetish.”), there are studies that laud natural cheesy bacteria.

In addition, the microbiota purportedly strengthen the quality of your gut bacteria, improving your immune and digestive systems. This seems to be more speculative that strictly scientific, but the claim seems fairly plausible. Diversity of microbes in your digestive tract has been linked to general goodness like weight-loss and less colon cancer. This assumes, of course, that diversity doesn’t include pathogens. Most importantly, native microbiota create a rich flavor profile and give cheese volatility (think deliciously stinky).

There is also, in fact, evidence that raw-milk is safer than pasteurized milk. Listeria is possibly the most worrying word in the dairy world, and this 2001 study suggests that it is actually more prevalent in pasteurized milk. The common explanation is that if milk is contaminated, it takes the full arsenal of native microbiota to eliminate the contaminant. Pasteurized milk is vulnerable in that regard, and Listeria roams unchecked. This is just one of a handful of concerning pathogens, but it’s the big one of the bunch.

The Pursuit of Healthiness-ness

The prevailing feeling (and we’re delving into waters where feeling matters a whole lot) is that raw milk has good-sounding things like nutrients and fortifiers that make you a generally healthy person. The Weston A. Price Foundation is a food advocacy group that emphasizes “wise” and “ancient” traditions in food. The sidebar on their homepage shows a picture of a family that looks straight out of an L.L. Bean catalogue. They’re all smiling and (visibly) happy. The caption reads:

They are happy because they eat butter! They also eat plenty of raw milk, cream, cheese, eggs, liver, meat, cod liver oil, seafood, and other nutrient-dense foods that have nourished generations of healthy people worldwide! Learn more about the foods that support radiant health for your family.

Not to be overly disparaging, but it’s easy to see how this rhetoric of nourishment and tradition sails right past scientific discourse like the proverbial ship in the night. It’s not just health—it’s radiant health that we’re after now, which seems to have a moral and even contrarian component. Eating raw-milk cheese, therefore, is not only healthy but an ethical subversion of the nutritional-industrial complex. And so on.

There is a format to the raw-milk-heals narrative. A person (usually white and wealthy) will tell a crowd about how sickly and diseased they used to be. These diseases are generally chronic, bothersome, but not life-threatening (tooth decay and eczema on one end of the spectrum, Crohn’s disease on the other). They will then relate their lifestyle switch, which usually hinges on raw milk but might be better classified as “going organic.” The conclusion, of course, is general strength, healthiness, and happiness. It’s easy to see the allegory for modern society: these chronic conditions could easily describe the aches and pains of American industrialized existence, and the “cure” of raw-milk represents anything all-natural, local, organic, etc.

Interestingly, anti-raw advocates will use the same format to respond to these claims. For every CDC study, there is a mess of accompanying videos with footage of distraught mothers. The narrative here is, “We tried raw milk because we listened to those other stories, and look where it got us.” Frankly, I find it easy to sympathize with the raw-milk camp in this comparison. How are they ever expected to get anywhere when they are levying their eczema-free skin against footage of dying kids on loop? It seems like the tit-for-tat approach of storytelling is a emotional trap, and perhaps best avoided all together.

Our society values risk-centric analyses. The argument that raw-milk cheese has benevolent, tasty microbes will always seem weak in comparison to CDC indictments, flawed though they may be. Oftentimes, it feels like raw-milk cheese health claims are pulled out of a hat as a means to compete in the cost-benefit analysis. We can better ignore the risk of pathogens if we convince ourselves that raw cheese is a magical cure-all. This seems silly and a little dispiriting. It can be tough to discern how clear a threat needs to be in order to make us rule out a given behavior. Should even the word “pathogen” be enough to send us running to the Kraft aisle? Is our goal only to minimize risk and maximize sterility and hygiene? Probably not, but drawing a line in these murky waters still seems difficult.

So We’re Two Posts in and I’m Still Crippled by Indecision at the Checkout Line

Look, the jury really still is out on raw cheese. My official recommendation would be to avoid thinking of it as medicinal in any way, just because the science is so underdeveloped and the evidence so specious. Then again, if you find yourself incredibly beautiful or able to speak several languages after eating raw-milk cheese, by all means don’t stop. Once again, the concerns over its safety seem rather mild. It is possible to eat raw-milk cheese after coming to an informed conclusion.

It also might be helpful not to think of raw-milk cheese as a single entity but rather a regionally distinct product. In a 2010 study in the Journal of Dairy Science, Vermont cheesemakers were lauded as paragons of safety. Despite frequent repeat testing on a wide range of small-scale artisan cheese operations, the study found “no detectable target pathogens.” Vermont enacts a system that permits raw milk and raw-milk cheese, but under strict regulation. Most famously, consumers retain the right to visit the farms themselves to inspect the process (although I doubt how effective the average consumer is at assessing the presence of Listeria in cheese). Vermont also has access to the Vermont Cheese Council, who will pay for cheesemakers to take classes on safety and quality control. If we as a society want to have access to the benefits of raw-milk cheese, we should pay attention to what works and what doesn’t. Vermont would be a good starting point.

Next week, I’ll get sociological with a look into the culture and politics of rawctivism. Stay organic my friends!