A cheese ingredient label invariably lists four essential components: milk, salt, rennet, and cultures. This tried-and-true combination is now standard, but you might be surprised to learn that the idea of cultures as an added ingredient is relatively new.

As a commercial product, cultures—the bacteria, yeasts, and molds used to make cheese—have been available since the late 19th century. But cheese has been made for nearly 9,000 years. Prior to the mid-1850s, milk’s transformation into cheese was poorly understood. Sans modern sanitation standards and refrigeration, milk soured and curdled on its own. While this was attributed to a range of forces, from angels to chemical reactions, in reality it was due to cultures: particularly lactic acid bacteria.

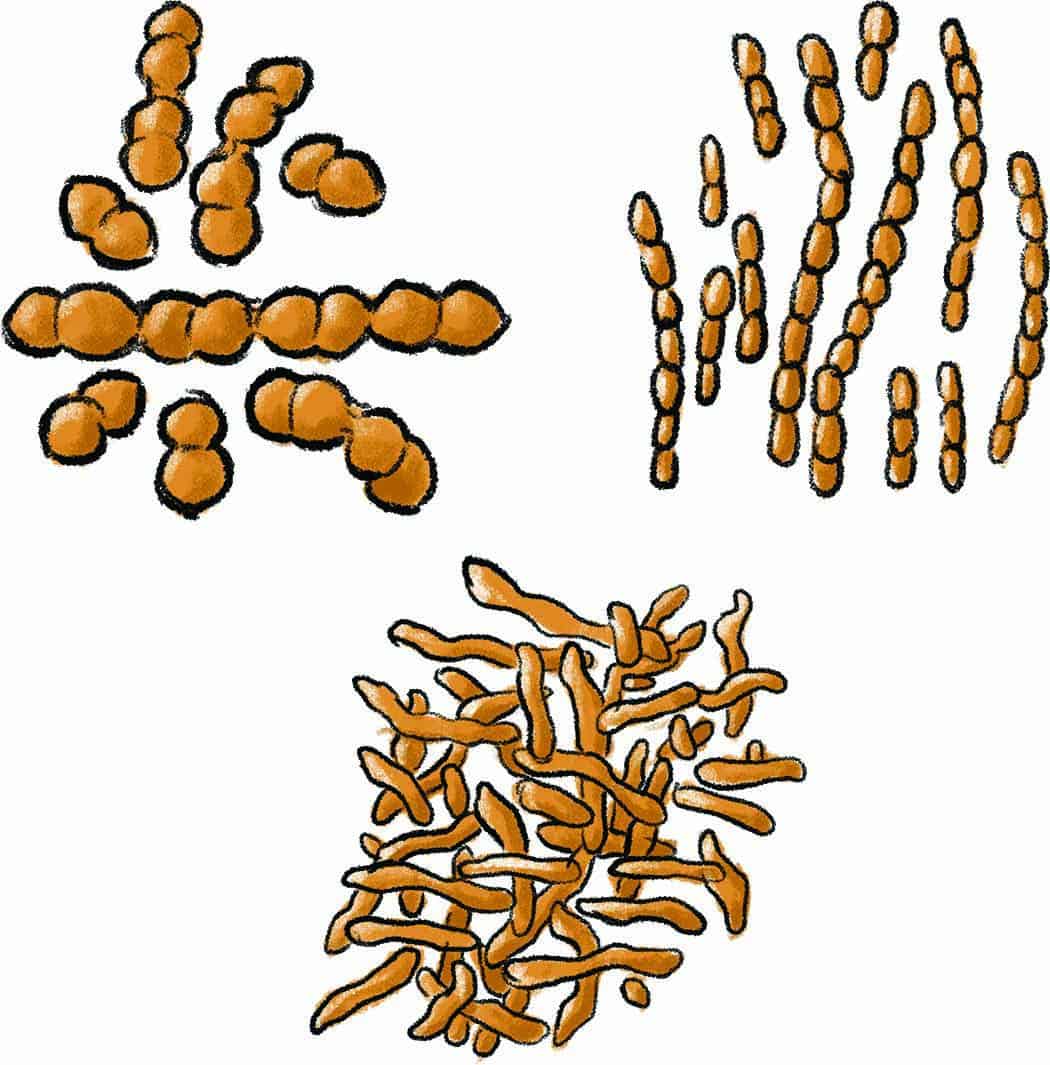

These types of bacteria are found all around us: in milk, in grass, and on our hands. In milk they consume sugar and convert it to acid, kick-starting curdling. The dirty milk buckets and ambient temperatures of yore were cheesemakers’ unwitting partners, allowing bacteria to thrive. Each region—each farm, really—unknowingly bred its own unique set of microbes.

Throughout millennia, microbes evolved, adapted, and thrived as the bases of traditional cheeses—until the acceptance of germ theory in the 1850s prompted a deeper investigation into the microbial world. In dairy, the result was twofold: A push was made to pasteurize milk in order to free it of potentially pathogenic microbes; at the same time, because cheese could not be made without microbes, commercially derived cultures were developed that could be added to milk for cheese manufacturing.

Today most cheesemakers use commercial cultures. The small number of biotech companies producing these freeze-dried microbes control much of the propagation and distribution of what has become a vital single-use ingredient—and some argue that this tramples diversity. In their 2017 book Reinventing the Wheel (University of California Press), authors Bronwen and Francis Percival call this trend a “holocaust of raw-milk microbes… [a] catastrophic destruction of microbes on which cheesemakers rely to make their raw-milk cheeses distinctive and unique.” Despite more than a century of homogenization, a small number of cheesemakers are pushing back, taking the time and effort to foster native microbes and increase biodiversity.

A slightly more traditional method than commercial starters, bulk farmhouse cultures are still going strong among some cheesemakers in Europe. These cultures were isolated from farms back when starters first became an added ingredient, and sometimes contain a more diverse mix of microbes than commercial starters. Such microbe-filled slurries have been propagated continuously by laboratories like that of Barber’s, a cheddar-maker in Somerset, England, which supplies the cultures to other traditional producers in its region.

Other cheesemakers are using methods that harken further back, harnessing their very own populations of bacteria. This can be achieved in a few different ways. One is though “backslopping”: using one day’s whey to culture the next day’s batch of milk. This method was traditionally used to make lactic-set cheeses. Another is by utilizing biofilms, communities of microorganisms that form residues adhering to a surface or are absorbed into a porous environment. For most of cheesemaking history, the material of choice was wood—which may seem solid, but it’s quite permeable. Raw milk can be stored in a wood bucket, its pores absorbing a rich community of microbes, including lactic acid bacteria. When the next day’s milk interacts with the wood surface, dormant microbes awaken to set the acidification process in motion. Though this method is uncommon, it’s an important component in the case of a few cheeses, including Salers Tradition from France, and Bethlehem from the Abbey of Regina Laudis in Connecticut.

Cornerstone from Birchrun Hills Farm

Another method of harnessing native microbes is through milk cultures, or “clabber”—that’s the secret behind Cornerstone. Each maker of the terroir-driven cheese—Peter Dixon and Rachel Fritz Schaal at Parish Hill Creamery, Mark Gillman at Cato Corner Farm, and Sue Miller at Birchrun Hills Farm—captured their own cultures in a similar way: Cows were hand-milked, then milk was put in sterile jars and left to “clabber” until natural microbes caused them to curdle. The best samples—those with a clean yogurt flavor and no gas bubbles—were added to pasteurized milk and incubated again. These “grandmother cultures” are the source from which all subsequent Cornerstone cultures are propagated.

Other more experimental methods have also been proposed for culturing milk. Kefir grains are gelatinous clusters of microbes, similar to the SCOBY you might use to make kombucha. Author and traditional cheesemaking advocate David Asher has argued that the grains can be used to make certain cheeses because of the goldmine of genetic material they harbor from bacteria, fungi, and yeasts. These cultures don’t fall into the FDA category “Generally Regarded as Safe” for commercial use, however; for now, they’re limited to home kitchen experiments.

Using native cultures doesn’t come without its challenges. Cheesemakers must produce them carefully and painstakingly to ensure consistency—a challenge even for the most seasoned. “It’s an investment of time, and it’s another dairy product you have to maintain,” says Parish Hill Creamery’s Fritz Schaal of the company’s microbe-rich clabber. But to her, the pros outweigh the cons: “It’s an expression of terroir, an ability to create a taste of place. It’s microbial and biological diversity. It’s about what matters to us,” she says. “Plus, we also happen to think the cheese is pretty damn good.”