In a recent #TBT post on Instagram, 20-something Marcus Samuelsson wears a black chef’s jacket and a serious, focused expression. “When I became the executive chef at Aquavit, there were times I felt like I was attached to a rocket. And to think I was just getting started,” the caption reads. At the time, in mid-1990s Manhattan, Aquavit was among the most celebrated restaurants in the world and Samuelsson was the youngest chef ever to receive a three-star review from The New York Times. Born in Ethiopia and adopted by a Swedish couple after his mother died when he was three, he was then thoroughly European in his approach to food and cooking. “No African memories claim him,” wrote Felicia R. Lee in a 1996 profile in the Times.

Samuelsson has since made his own African memories, traveling multiple times to Ethiopia, meeting his birth father, and immersing himself in the food and culture. His career has meanwhile flown well into the stratosphere—a journey fueled by talent, drive, and the search for a place to land. He found it in Harlem, where he has lived since 2004, and where he opened the first Red Rooster, a lively (pre-pandemic) restaurant serving an eclectic menu of comfort food, in 2011. Samuelsson’s empire now includes Red Rooster outposts in Miami and London, plus other restaurants in New Jersey, Chicago, California, Montreal, Bermuda, and Scandinavia. He has authored or co-authored seven cookbooks and a memoir; he’s also won Top Chef Masters, Chopped All Stars, and six James Beard Awards, including one for his current PBS television show, No Passport Required. In 2009 he married Ethiopian-born model Maya Haile; they have a four-year-old son, Zion Mandela.

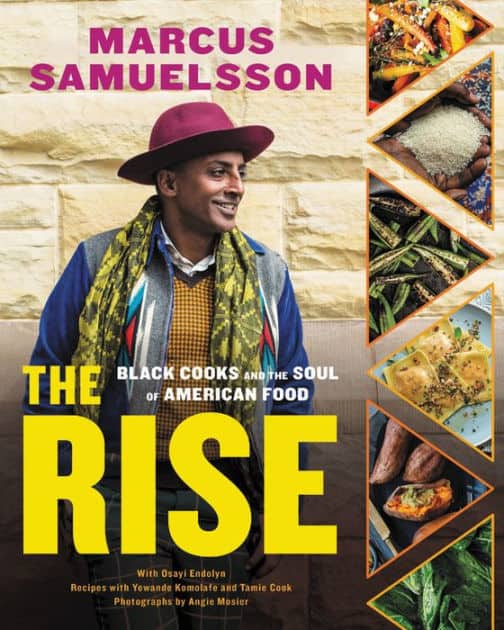

Last October, Samuelsson debuted his latest achievement, The Rise, an ambitious cookbook and treatise on Black cooking in America, co-authored by acclaimed Southern food writer Osayi Endolyn. Each of the first four chapters is dedicated to a pantheon of Black chefs, home cooks, authors and activists—from New York winemaker André Hueston Mack and television host Carla Hall to Seattle restaurateur Edouardo Jordan and the late New Orleans icon Leah Chase. The rich, multilayered story of what Samuelsson calls “the soul of American food” is woven through their stories and the companion recipes. The book is both beautiful and a powerful, compelling read, its significance compounded by the confluence of the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement. In addition to his usually frenetic schedule, Samuelsson and his team have been feeding the hungry from his restaurants in predominantly Black neighborhoods, including Harlem. He agreed to answer questions via email.

Susan Axelrod: You write in your poignant Author’s Note that The Rise is a response to a pivotal moment in American history. However, a book of this depth and breadth must have been in the works well before the pandemic and visible police brutality pushed the crisis of systemic racism into the spotlight. When did you conceive the book, and did its focus shift as a result of the events of the past year?

MARCUS SAMUELSSON: We started working on the book four years ago. Once we completed the book, I felt the need to address both the pandemic and systemic racism that made national attention in early 2020. After the devastating news about Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and COVID I had no choice but to stop and reflect on that within the first pages.

I remember the excitement around the opening of your original Red Rooster in Harlem—your first foray into cooking Black food for the public. How has your understanding of Black food changed in the last decade? Is there a discovery that especially surprised you?

MS: Black food is many things and I am continuing to learn about its evolution. I cooked African and Ethiopian food for years before opening up Red Rooster. I’ve cooked in Africa and have enjoyed eating the local cuisine. The goal of the book is to unpack how Black food is not monolithic, it’s many things. I learned more about the foods of the migration and southern foods at Red Rooster. I learned a lot about the lack of Black authorship from the incredible profiled chefs, farmers and historians in The Rise. I’m having a parallel journey with my readers since I’m evolving and learning as well.

The countries of your heritage—Sweden and Ethiopia—seem as though they would be on opposite ends of a spectrum when it comes to food and food culture. Yet you have been able to meld both into your culinary career. How are they similar, and how does each tradition continue to inspire you?

MS: They’re similar in terms of the enormous amount of pride in both countries. Both have traditions of preserving whether it’s salt and sugar in Sweden or berbere in Ethiopia. Both have raw culture as well; in Ethiopia there’s kitfo and in Sweden there’s gravlax. Unique breads such as injera in Ethiopia and crispbread in Sweden are huge in each country. In Ethiopia, there’s a much larger emphasis on spiritual cooking and the connectivity between spirituality and food. I constantly draw inspiration from both countries in my cooking and have so much fun combining the two.

What is the most important thing that people can do to be more aware of the fact that Black food is “the soul of American food?”

MS: What Yewande [Komolafe] and Osayi do so well here is draw out these unique stories from these incredible Black chefs and experts in the culinary field. I hope readers will cook from the book, be curious, and order from their local Black restaurants. More importantly I want food to create a dialogue surrounding race, culture and identity in a way we haven’t before—similar to the way we’ve been able to have these discussions in relation to music and art.

At culture, we support efforts to bring diversity to the largely white artisan cheese world, and we want to include more Black voices in our stories. Do you have any ideas for us?

MS: Black craftsmanship inspires me in many ways. I always look to music and artists like Derrick Adams, Julie Mehretu and Sanford Biggers. There are many people in the food space I admire like Mashama Bailey, Adrienne Cheatham, Nyesha Arrington, Ron Finley and Karen Washington. I see the present and future within the intersection of artistry and craftsmanship within these chefs.

Recipes reprinted with permission from The Rise by Marcus Samuelsson (Voracious, October 2020)

Berbere Spice Brown Butter

Ingredients

- 1 pound butter

- 1 small red onion chopped

- 3- inch piece fresh ginger peeled and coarsely chopped

- 3 cloves garlic minced

- 1 cinnamon stick

- 4 cardamom pods

- 1 teaspoon fenugreek seeds

- 1 teaspoon ground cumin

- 1 teaspoon dried oregano

- ½ teaspoon ground turmeric

- 4 sprigs fresh thyme

- 1 tablespoon berbere seasoning

Instructions

- ►Melt butter in a medium saucepan over low heat, stirring occasionally. As foam rises to the top, skim and discard it. Continue cooking, without letting the butter brown, until no more foam appears. Add all ingredients except for berbere seasoning and continue cooking for 15 minutes, stirring occasionally, until onion is lightly browned and aromatic.

- ►Remove from heat and set aside to infuse for 30 minutes.

- ►Strain through a fine mesh strainer lined with cheesecloth and return to a clean saucepan over low heat. Add berbere spice and stir to combine.

- ►Store refrigerated in an airtight container for up to 3 weeks.