Let’s get one thing straight: Gooseberries are only related to geese by name, but otherwise bear no scientific connection. Etymologists are divided on the origin of this berry’s name and the answer will vary depending on who you ask. Some say the “goose” comes from a devolved form of the Dutch word for the berries (kruisbes), or the French groseille (currant). Oxford English Dictionary editors believe a pattern emerges in traditional recipes featuring gooseberries. The French word for gooseberry, groseillier à maquereau, literally translates to “mackerel berries” because the berries are used in a classic mackerel dish. By this logic, perhaps Old Englishmen prepared roast goose with gooseberry sauce and this is the name that stuck. Linguistic debates aside, the exact association with fowl remains unknown.

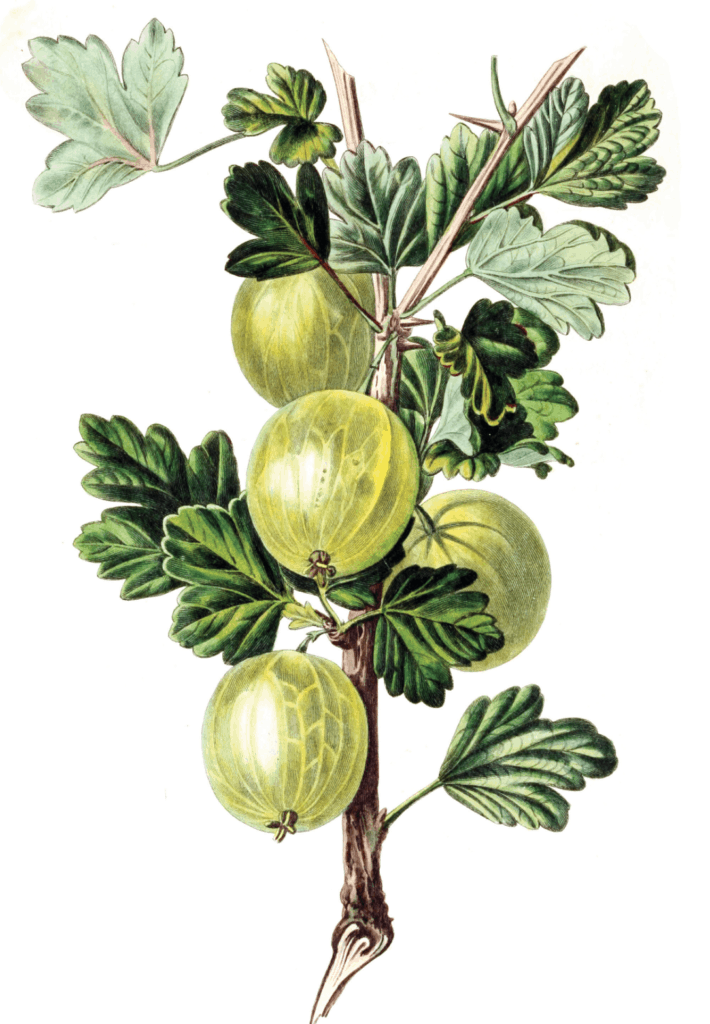

The gooseberry, or Ribes uva-crispa, is a cousin of the common currant (another member of the Ribes family) and second cousin once removed of the grape. Known as goosegogs to the Brits—arguably the first growers of the gooseberry—, these grape look-alikes are indigenous to most of Europe and western Asia, though the climate of the British Isles is particularly suited for gooseberry cultivation.

Gooseberry bushes, which grow up to 5 feet in width and height, have been around for so long (we’re talking Ancient Rome) that it’s difficult to pinpoint their exact origin. To further complicate the issue, these bushes grow wild across the European and Asian continents and it’s near impossible to distinguish between feral and domesticated plants. There are vague references to gooseberry-like foods in Ancient Roman texts, but the first indisputable reference to a gooseberry doesn’t appear until naturalist William Turner’s 16th century Herbal, and soon after in an 18th century poem by farmer-turned-poet Thomas Tusser. By the end of the 18th century, the gooseberry had become a garden go-to for cottage horticulturalists across Britain.

For fresh gooseberries in the year 2020, stop by an English market or grocery store beginning in late June through the end of July and look for green and pink varietals. This is peak gooseberry season, when you’re likely to get the sweetest, most ready-to-eat product; but even when they’re at their ripest these berries have a tartness somewhere between a kiwi and a kumquat. Many grocers sell their gooseberries underripe, so take care to let these ripen for a day or two or use the sour berries for cooking. Early pickings make for great jammy desserts like pies and crumbles.

If you’re not planning to make it across the pond anytime soon, fear not; North America has several of its own gooseberry subspecies, available in places like Maine and the Canadian Maritimes alongside other summer crops. For a festive dessert, whip up a Gooseberry Fool (recipe below) and you’ll be transported to the English countryside with this 16th century British treat.

Gooseberry Fool

Ingredients

- 3 cups pink or green gooseberries about 1 pound

- ½ cup granulated sugar

- ½ cup heavy cream chilled

- ¼ cup mascarpone

- ¼ cup superfine granulated sugar

- Mint for garnish (optional)

Instructions

- ►Pull off tops and stems of gooseberries and halve berries lengthwise. In a heavy skillet cook berries and granulated sugar over moderate heat, stirring occasionally until liquid is thickened, about 5 minutes. Add water as needed to prevent gooseberries and sugar from sticking to the pan or burning.

- ►Simmer mixture, mashing with fork for an additional 2 minutes over heat.

- ►Remove from heat. Cover gooseberry pulp and chill until cold, about 1 hour, and up to 1 day.

- ►In a medium-sized bowl, use an electric mixer to beat heavy cream with mascarpone until it holds soft peaks. Add superfine sugar and beat until mixture just holds stiff peaks. Fold chilled gooseberry pulp into cream mixture until well-combined. Fool may be made 3 hours ahead and chilled, covered. Garnish with mint when serving.