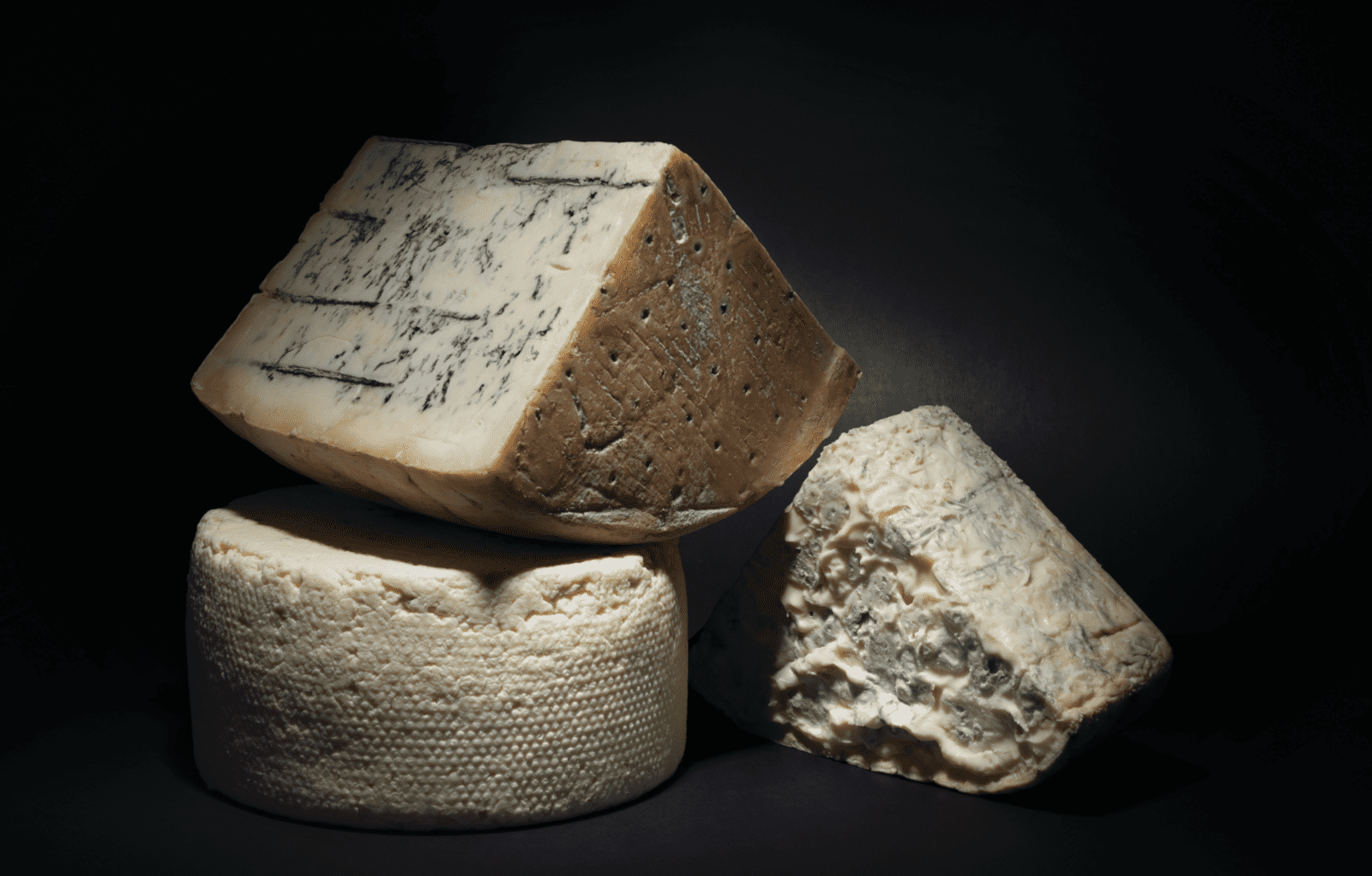

Photographed by Adam DeTour; Styled by Catrine Kelty

Folks like to spin yarns about blue cheese. Most frame it as an accidental discovery—in one French legend, a shepherd got drunk and passed out in a cave, leaving his rye bread and sheep cheese to comingle in the dank air. Another version paints the inventor as a lovesick cheesemaker who abandoned his curd to chase a farm girl, and it’s this lusty myth that people in the foothills of the Italian alps turn to when explaining the origins of one of Europe’s first blues: gorgonzola.

Not quite the oldest (Roquefort was mentioned by Pliny the Elder in 79 C.E.), gorgonzola is still up there—some claim it was created in 879 C.E., while others set the stage in the twilight years of the Roman Empire. Back then, the Valsassina mountain valley was the only passable route through the Italian Alps. It carried traffic from central Europe down to the fertile Po Valley, and cowherds shuffling transhumant cattle from summer highlands to their winter homes in the plains.

On their way through, these herders stopped in small towns to milk their cows, often leaving milk with their hosts as a thank you. The residents of villages like Valsassina and Gorgonzola had more milk than they could drink, so they made cheese—stracchino, from the Italian word for “tired,” to honor the roving cattle.

But how did stracchino become gorgonzola? “A dairy apprentice in love,”says Alberto Ciresa, a third-generation gorgonzola affinatore (someone who ages cheese). “The apprentice was left alone in charge of the cheese making, but instead of finishing the task he sneaked off to meet his girlfriend. The next morning, fungus was spreading over the curd, but he covered up his negligence by mixing the curd…with a new batch. Some months later, when the cheese matured, the marbled interior revealed the scam.

That scam became legend. “The two curds, obviously having different textures and different temperatures, did not perfectly mix, leaving spaces in the texture’s structure where the natural blue mold developed,” says Giovanni Guffanti Fiori, a fifth-generation gorgonzola affinatore. According to Fiori, this method is rare today: “To ensure that the blue mold develops in the cheese…the penicillin is placed directly into the curd.” Now, pasteurized milk is inoculated with Penicillium glaucum (native to the caves of Valsassina) right away, and the resulting curd drained, shaped, salted, and taken to a camerino (a hot, humid room) to develop internal mold. The cheeses are pierced with copper needles after four weeks to introduce oxygen to the interior, further stimulating that blue patina that Italians refer to as erborinatura, from their word for herbaceous.

Gorgonzola DOP Dolce

Some cheesemakers still use traditional methods, producing gorgonzola del nonno or gorgonzola antico with only naturally-occurring mold, or gorgonzola due paste by adding drained evening curd to morning milk. But whichever methods they use, all must follow the rules of the gorgonzola Consorzio. PDO gorgonzola must be made in specific provinces within Lombardy or Piedmont, using milk from cows inhabiting these provinces and eating at least 50 percent feed grown there. Today, there are 39 cheesemakers in the Consorzio, with 1,800 farms supplying their milk. In 2019, Consorzio members produced 5,025,785 wheels of gorgonzola PDO.

This popularity derives, in part, from variety. “The spectrum gorgonzola swings is wide and unlike any other blue cheese family,” says Tess McNamara, head of salumi and formaggi for Eataly North America. “It’s such a time-honored cheese because gorgonzola captures the blue cheese lover with both versions.” Those two versions are gorgonzola piccante and gorgonzola dolce. The piccante came first, and is also referred to as gorgonzola naturale, gorgonzola stagionato, or gorgonzola mountain (the last of which sounds like a ride at Disneyland Italy). It’s dried longer, aged a minimum of 80 days, and can be made with penicillium Roqueforti as well. Its butter-yellow paste is streaked with deep marine veining and tends to be firmer. “During the production of gorgonzola piccante, the curd is cut in really small pieces,” said Alesso Ciani, of gorgonzola affinatore La Casera. “That’s what makes the cheese paste harder.”

Gorgonzola dolce came along after World War II, when both milk production and refrigeration shot up. “The piccante type could be stored and maintained for a longer time,” said Ciresa. “The introduction of technology allowed consumers to handle a softer type.” This milder, creamier gorgonzola (aged a minimum of 50 days) became a fast favorite—nowadays, the spicier piccante makes up just 10% of total gorgonzola PDO production.

Non-Italian riffs on the style straddle a line between sweet and spicy. At Rogue Creamery in Oregon, David Gremmels creates a variety aged long enough to be considered piccante, but uses native yeast strains for a result that is fruitier than its Italian counterpart. In Wisconsin, Sartori Cheese infuses its Dolcina Reserve with cream for an extra-rich paste, but ages it long enough to be sliceable. American artisan gorgonzolas also tend to be farmstead, which is less common in Italy.

“Gorgonzola producers usually don’t have their own farms,” says Ciani. “Most of them have dozens of milk-bestower farms who give their milk to the producers.” In this production ladder, farmers give milk to cheesemakers, who in turn give wheels to affinatores to age them. In this way, today’s model mirrors the founding set-up in Valsassina and Gorgonzola, when herders gave milk to village cheesemakers—only now, that mold is no accident.

Valley Ford Cheese Grazin’ Girl

GORGING ON GORGONZOLA

Though eating it straight is never out of the question, we have some tips on how to enjoy this blue to the fullest.

+ POLENTA: “One of the most common recipes of northern Italy is polenta and gorgonzola,” says La Casera’s Alessio Ciani. Eataly’s Tess McNamara echoes this suggestion: “There’s nothing better than a steaming bowl of slow-cooked polenta topped with gorgonzola. Add a dollop of butter, too.”

+ CRESPELLE: Ciani recommends filling these paper-thin Italian pancakes with gorgonzola—try with radicchio and pancetta folded in, too.

+ FRUIT SALAD: Though pears and walnuts are traditional, McNamara says any fruit will do (though her preference is stone fruit—think peaches or dried cherries).

+ GRISSINI: “Grissini, the Italian ‘breadstick,’ is the perfect companion to gorgonzola dolce,” says McNamara. “Northern Italy makes grissini for this very reason, I am convinced!” The soft cheese can be easily scooped up by these crispy batons.

+ PIZZA: Liven up a white pie with gorgonzola, pear, walnuts, and prosciutto.

+ RICE/PASTA: Both piccante and dolce can be transformed into a decadent cream sauce or stirred into a risotto just before serving.

Tasting Notes

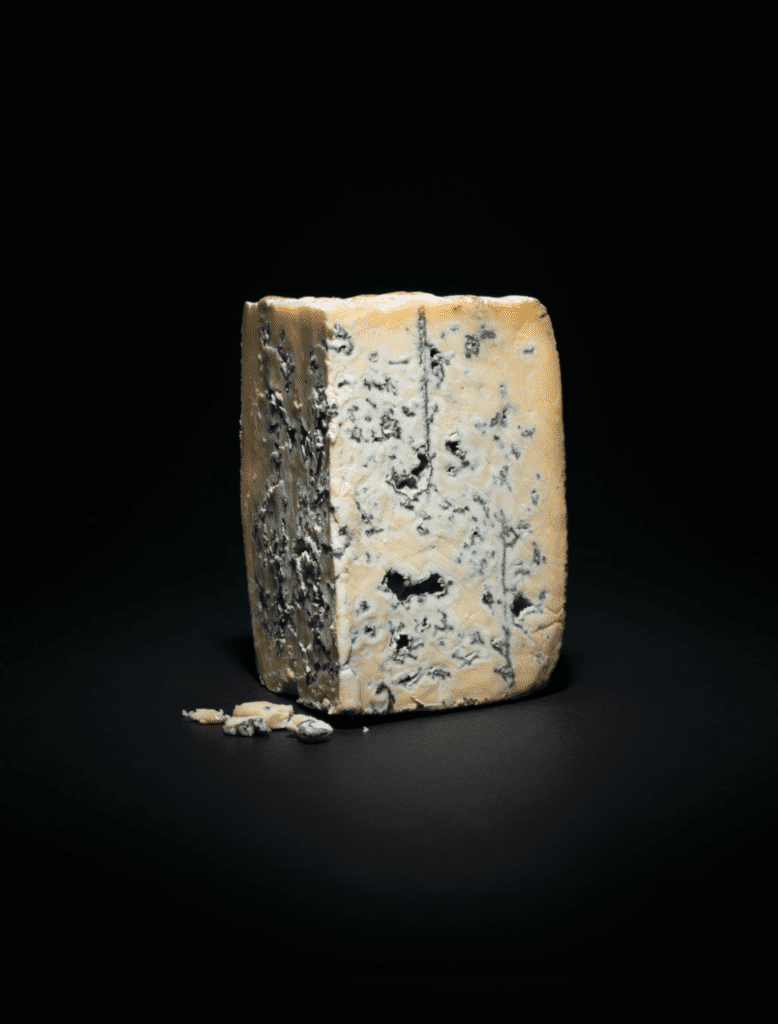

Gorgonzola DOP Piccante

Novara, Piedmont

Pasteurized cow’s milk

Luigi Guffanti started seasoning cheese in a depleted silver mine in 1876; today, his grandsons maturew heels in a former sausage factory. Their piccante ages for at least 90 days and sometimes up to 300, producing a dense ivory paste with navy dappling and invigorating sharpness.

Gorgonzola Prelibato

Novara, Piedmont

Pasteurized cow’s milk

Alberto Ciresa ages gorgonzola made at Caseificio Pedretti, right in the beautiful Parco Ticino nature preserve. Until last year, the Pedretti’s 92-year-old Nonna was still making cheese with her three sons—she attributed her youth to eating gorgonzola every day. Their Prelibato is spoonable at fridge temp, with a milky white paste, thirst-quenching effervescence, and crags of pale blue mold that evoke a forest after rain.

Dolcina Gorgonzola Reserve

Plymouth, Wisconsin

Pasteurized cow’s milk

Using milk from neighboring family farms, the cheesemakers at Sartori craft a gorgonzola that takes “dolce” to a whole new level. Infused with cream, the Dolcina Reserve’s white paste takes on the richness of ice cream, with pops of spicy teal to keep you on your feet.

Gorgonzola DOP Dolce

Verbania, Piedmont

Pasteurized cow’s milk

La Casera’s Eros Burrati grew up behind the counter of his parents’ cheese shop. Today, he ages a melty gorgonzola dolce that many mongers sell by the scoop rather than the wedge—some even display whole wheels in a dramatic top-down presentation. Burrati ages his three months to get its characteristic citrus tang, cream-top hue, and soft blue bumps.

Gorgonzola Cremificato “Spoon Gorg”

Bergamo, Lombardy

Pasteurized Cow’s Milk

Arrigoni Battista began making gorgonzola from a family recipe in 1920; to this day, Arrigoni crafts cheese using the milk of their own dairy cows. Their cremificato will defy your cheese slicer—as the nickname suggests, it’s best served with spoons. Arrigoni even suggests pouring a little champagne float over the cheese on special occasions!

Oregonzola

Grants Pass, Oregon

Raw cow’s milk

To create an American gorgonzola, Rogue’s David Gremmels turned to his friend Ig Vella, a fourth-generation Italian cheesemaker, for help sourcing mold from Italy. Aged six months and laced with intermittent ocean-green veining, his Oregonzola hits you with a histamine spice at first, then relaxes into a fudgy cream finish full of pineapple sweetness that’s hard to put down.

Grazin’ Girl

Valley Ford, CA

Raw cow’s milk

Karen Bianchi-Moreda runs Valley Ford Cheese with her son, cheesemaker Joe Moreda, Jr. Their Swiss-Italian family heritage inspired Joe to attempt this Alpine blue—his version is aged 90 days to achieve its compact, slightly crunchy paste full of Christmas-cookie spice, citrus zest, and barnyard funk.y