Illustration by Sonic Yonix

Consider yourself lucky if you’ve seen a sign with that phrase, which translates to “queso fresco for sale,” anywhere in the US. I used to see it often in my old neighborhood in Brooklyn. Since I moved to Michigan, I started making my own cheese at home. I’ve still never found some of the more unique cheeses from Mexico that I miss: Mountain Cotija, Queso de Bola de Ocosingo, or queso del moral enchilado.

We like to think that we “vote with our dollars,” but we often misjudge that the products in our neighborhood stores are there because of social, cultural, and even political decisions made by importers, distributors, legislators, and regulators. If you want to learn more about these decisions, just consider: Who is or is not present in the cheese case?

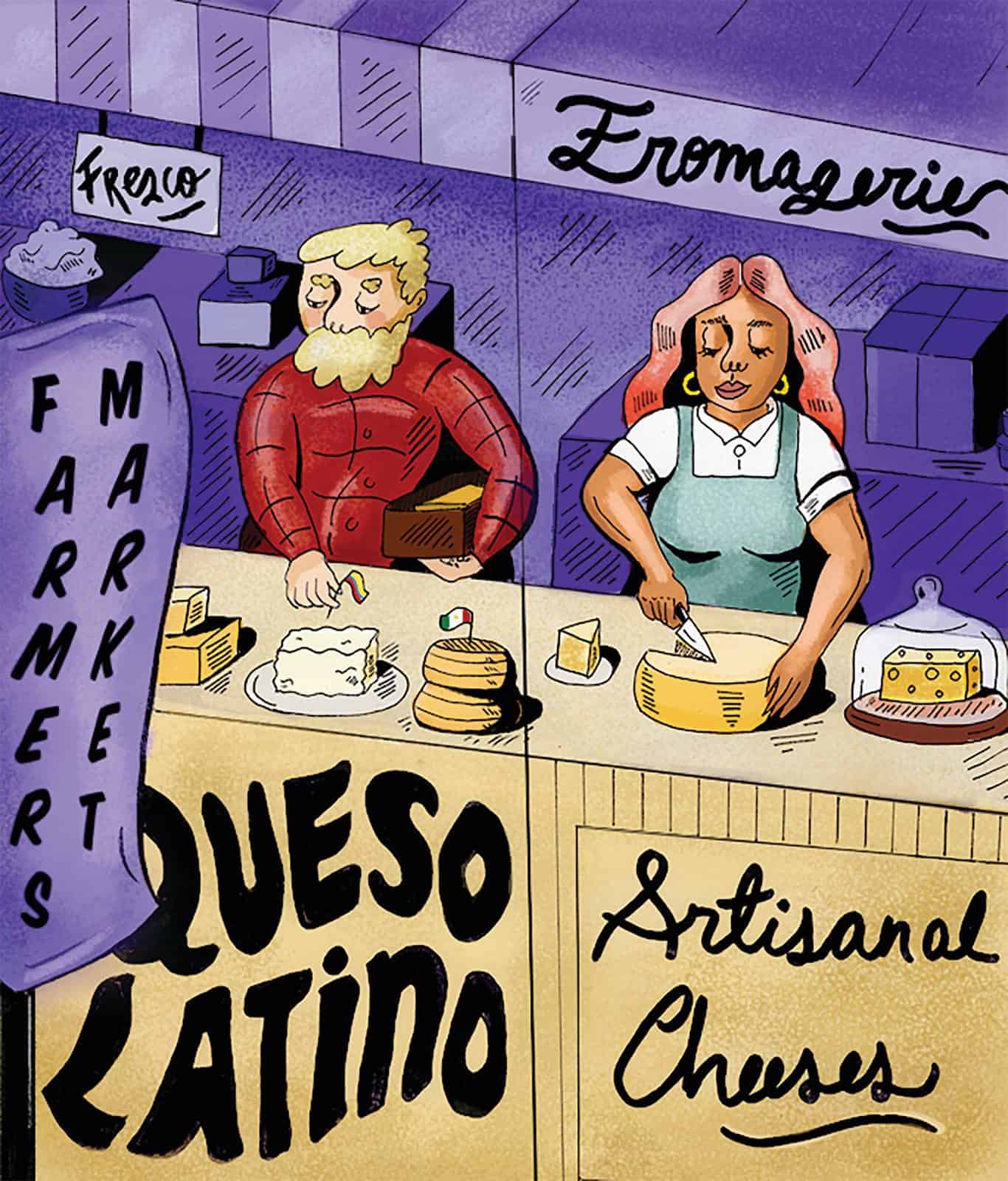

Behind America’s most prestigious cheese counters, Latin American cheeses are remarkably absent. Of course, you can find some of these cheeses in ethnic stores—but even then, the quality is only comparable to what you would find in a generic supermarket in their countries of origin. This doesn’t mean that there aren’t high-quality artisanal cheeses in Argentina, Mexico, or Costa Rica. We just don’t get them yet.

Instead you’ll find cheeses made primarily in North America and in Europe. And when mongers and restaurant servers mention the craftspeople behind US-made cheeses, you’ll hear names of white Americans, or perhaps immigrant cheesemakers from France, the Netherlands, and the UK. Their craftsmanship is impeccable and their accolades merited—but the names you don’t often hear are those of Hispanic-American and Latin-American immigrants.

Some are well known—Mariano Gonzalez originally from Paraguay and now at Grafton Village Cheese; Veronica Pedraza from Miami, Florida of Cuban descent; and Emiliano Amir Tatar from Argentina, of Merion Park Cheese, for example. But what we often forget is that Latin American immigrants form the backbone of cheese plants and factories all over the country. Much like in restaurant kitchens, immigrants from Mexico, Guatemala, and El Salvador are the core personnel of many cheese operations. Even if the cheeses they produce are not in Latin American style, they are Latin American cheesemakers. Their indelible contribution should make us question how we define Latin American cheese.

Further complicating matters, you’ll find some artisan cheeses with Hispanic-sounding names that aren’t tied to any particular Latin American or Spanish cheese tradition. Take, for example, Queso de Mano from Haystack Mountain Cheese in Colorado, an aged raw goat’s milk cheese with deep almond notes and an aroma of warm hay, made by Jackie Chang, an immigrant from Taiwan. In Illinois, Prairie Fruits Farm & Creamery makes Pelota Roja, a semi-firm goat’s milk cheese that’s reminiscent of paprika-rubbed wheels from the Canary Islands—but it’s rubbed in guajillo chile, a common ingredient in Mexico.

You’ll also find stellar American-made takes on more typical Latin American styles. In Oregon, Mexican immigrant Francisco Ochoa makes Don Froylan Queso Oaxaca, a pulled curd cheese shaped into a knot inspired by Oaxacan quesillo de hebra. Narragansett Creamery, a Rhode Island company specializing in mozzarella, also makes versions of queso fresco and queso blanco that are fresh and tangy, with a perfect acidity as is common in their Latin American counterparts.

While it’s probably wrong to consider these cheeses “authentic,” it’s also oversimplifying to dismiss them as “stolen.” Not only do they have great stories behind them—they taste amazing. They break the mold of what we consider American cheese.

Instead of drawing imagined borders between “American” and “Latin American” cheeses, or between well-known cheesemakers and those who labor in the background, what if we focused instead on celebrating the work that goes into creating great cheese? That means creating conditions for all cheesemakers—named and unknown, lauded and novice, US-born or immigrant. Let’s reward that work not only by paying the full price for good food, but by working towards political changes—amnesty for undocumented migrants, healthcare access for all, freedom to relocate, and wealth redistribution—that give dignity to the makers behind the scenes.