One Bite Ahead is featured in our Cheese+ 2017 issue.

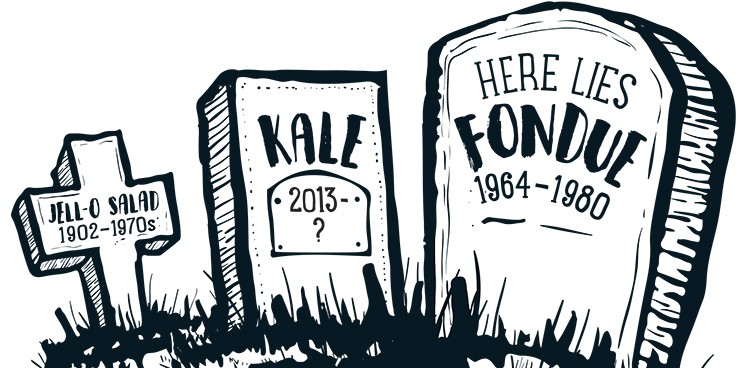

Picture polyester pantsuits, lava lamps, shag carpeting—and right in the middle of it all, a pot of bubbling cheese. Is there an image that better captures 1970s nostalgia? Food fads have existed since at least the Pleistocene era—when humans helped chase the woolly mammoth into extinction—but among modern culinary crazes, fondue is king. It’s “the great mid-century American food trend,” says David Sax, journalist and author of The Tastemakers (PublicAffairs, 2014).

My quest to unravel the many forces shaping our collective appetite began with a seemingly simple question: Where do food trends begin? Fondue seemed a good starting point. Sure enough, beneath the melty cheese were trendsetting forces at work. In my head it’s rather James Bond: Men sitting around a long table in a gilded room, faces obscured by darkness, plotting a path to global fondue domination. Indeed, it was the Swiss Cheese Union—a cartel that controlled cheese production in Switzerland for decades—that intentionally jumpstarted the fondue fanaticism that ultimately swept our nation.

In Switzerland, there were always plenty of wedges and wheels to sell. But unlike French diners, for example, Swiss and American consumers didn’t eat a cheese course with every meal, explains Dominik Flammer, author of Swiss Cheese: Origins, Traditional Cheese Varieties and New Creations (Shoppenkochen, 2010). To promote consumption, the union decided to push a little-known dish from the Alps, made entirely of molten curds.

“They invested a lot of money in marketing campaigns for fondue worldwide,” Flammer explains. “And the United States was a very important market for them.” It worked: After debuting at the New York World’s Fair in 1964, the dish oozed its way into American restaurants and homes from coast to coast.

Becoming Trendy

Is an aggressive marketing campaign the key to creating a food obsession? Perhaps in the past, says Dana McCauley, food trend consultant and CEO of Toronto-based startup incubator Food Starter. Traditionally companies pushed trends to market by advertising, pitching journalists, and coercing cookbook authors to seduce the masses. Today, however, trends can start with people. “A person with an Instagram account can [roll] a pebble down a mountain, and it can snowball,” McCauley says. “That wasn’t the case 20 years ago.”

Take the Cronut. Sure, we’ll give New York chef Dominique Ansel props for creativity—but would his donut-croissant mashup have exploded as it did without the web? Before he even released the pastry in May 2013, a blog post about the Cronut went viral. By the third sales day, a line of 100 people snaked around the block. This happened around the time Instagram was becoming popular. Soon enough, photo feeds were plastered with the flaky disks.

Not only does this overnight celebrity illustrate the fickleness of modern appetites—it shows how arbitrary trends can be. Post-Cronut, Ansel continued to pursue hybrid-pastry glory, inventing the Waffogato, the Cookie Shot, and the Frozen S’more. But none of his newer creations ever quite caught on.

“Creating a food trend is kind of like creating a hit song,” Sax says. “There’s no formula to it. You can try and try, and it just doesn’t work.”

Complicating all this are influencers aplenty vying for our attention. In one corner, imaginative chefs introduce new concepts to the mainstream. Before René Redzepi started scouring Danish countryside for mosses and seaweeds to stock Noma’s kitchen, few of us were eating foraged foods; if David Chang hadn’t launched Momofuku, we might not be stuffed with pork buns and ramen today. Then there are cutting-edge scientists who enhance flavors via chemical engineering and conceive new hybrid plants and meat substitutes. Meanwhile health evangelists develop diets—from South Beach to Atkins to Paleo—that outline what not to eat to achieve slimness, strength, and longevity (or so they claim).

Eager to understand these myriad forces, companies devote substantial resources to staying ahead of the curve. That may mean hiring someone like Christine Couvelier, CEO of consulting company Culinary Concierge. I asked her how she’s able to spot trends as they emerge. “Being externally focused,” Couvelier says. “Keeping my eyes open and my taste buds willing to try new things.” She travels to food shows worldwide, cooks with chefs, tours farmers’ markets and gourmet shops, and reflects constantly on everything she’s seen.

Another forecasting challenge: Trendiness straddles a line between a consumer’s desire to fit in and his or her desire for novelty. The moment a fad crosses the threshold into widespread popular culture, it’s the beginning of the end. By the time Dunkin’ Donuts released the Croissant Donut, for example, social media-savvy foodies had already moved on to cake pops and matcha macarons.

“It’s almost like you only know it’s a trend after it’s happened,” Sax says. Luckier crazes might lose their buzz but find a permanent place in our cupboards (i.e. olive oil). Others fade into the background or become punchlines (sorry, Cronut).

Can Fondue Make a Comeback?

To me, a child of the 80s, fondue was always more symbolic of a dusty Goodwill shelf than a dinner party. That is, until I moved to Switzerland—where the iconic dish still reigns supreme—and tasted it for the first time. Smothering crispy bread crusts in an amalgamation of the world’s best cheeses and scraping the browned bits from the bottom of the pot, I was instantly hooked. Since then I’ve gone to great lengths—working in a cheese cave, scaling mountains to high-altitude restaurants, even marrying a Swiss guy—just to eat more of it.

After all of my research, I began to wonder if trends ever die, really. Selfishly I wanted to know if there’s any hope for a stateside resurgence of my favorite Swiss meal.

“Sorry, Molly, no,” McCauley says. “It’s like the ’67 Mustang your uncle keeps in the garage and brings out once a year. You’re going to do it every once in a while, because it’s retro. But no, I don’t think it will come back.”

Until she sees a fondue restaurant with lines out the door, McCauley is skeptical. Plus, she says, buzzy foods typically fit into broader health trends, and fondue contains two of the ingredients that folks eschew most often these days: bread and dairy.

Despite his book title’s discouraging subtitle (Why We’re . . . Fed Up with Fondue), Sax is slightly more optimistic. First, he assures me that I’m not crazy. “When a food trend dies,” Sax says, “that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s any less tasty.” And there are a few things that reinvigorate trends, he adds. One is culinary ingenuity or the reinvention of a familiar dish. “What can you do to fondue to make it different, to make it unique and relevant to the way people eat today, the types of flavors and ingredients they want?” Sax asks.

Denise Purcell, the Specialty Food Association’s resident trend expert, tells me that people are craving wellness drinks with apple cider vinegar, DIY kits, and chickpea crisps currently. According to McCauley, it’s cauliflower and Korean cuisine. And Couvelier points to turmeric, mocktail mixology, and a waffle-everything movement.

Anyone for gochujang-and-turmeric fondue with chickpea crackers, DIY waffles, and pickled cauliflower for dipping, washed down with an alcohol-free, apple cider vinegar tipple?

OK, maybe not. But there’s hope for forgotten foods yet, as certain cultural shifts encourage nostalgia. When people feel confident (if the economy is strong, for example), they’re more willing to try bold new flavors, Sax says. In times of uncertainty, they revert to comforting foods.

So on the days I’m feeling sentimental, I’ll mix up the Alpine wedges, light the fondue pot, post a pic on Instagram, and hope you’ll join me. If not, I’ll still find solace in all that gooey goodness.