In 1904, cornflake kingpin John Harvey Kellogg created a soft, spreadable nut pâté called Nuttolene that he marketed as a dairy-free replacement for cream cheese, unwittingly kicking off a debate that riles our industry to this day.

Kellogg was a turn-of-the-century hippie, fixated on the personal spiritual benefits of veganism in an era when purity and abstinence were cardinal virtues. His work dovetailed with that of Upton Sinclair, whose exposure of unsanitary practices in the meatpacking industry fueled widespread fears of diseases traceable to tainted animal products. This era’s interest in veganism was based on individual aspirations and fears—it was niche, and it didn’t last long. A depression and two world wars pretty much knocked it out.

But one hundred years later, vegan cheese is back on the menu and bigger than ever. In 2021, the global vegan cheese market was valued at $2.43 billion, and Silicon Valley is pouring more money into alt milks every year. So what’s changed? The planet is heating up, and it’s not just about us anymore.

“Cheeses that are coagulated with rennet have elasticity to them because of the manner in which the proteins connect. This is why lactic goat cheeses are not made in large formats, they will fall apart. In vegan alternatives, there is no coagulum, nothing to cheddar or press. It doesn’t stretch or knot together. Unless you start adding gums, stabilizers, and emulsifiers, your product texture would be like a lactic cheese, like a goat or cream cheese.”

—Yoav Perry on why you don’t see more long-aged vegan cheeses

What’s in a Name?

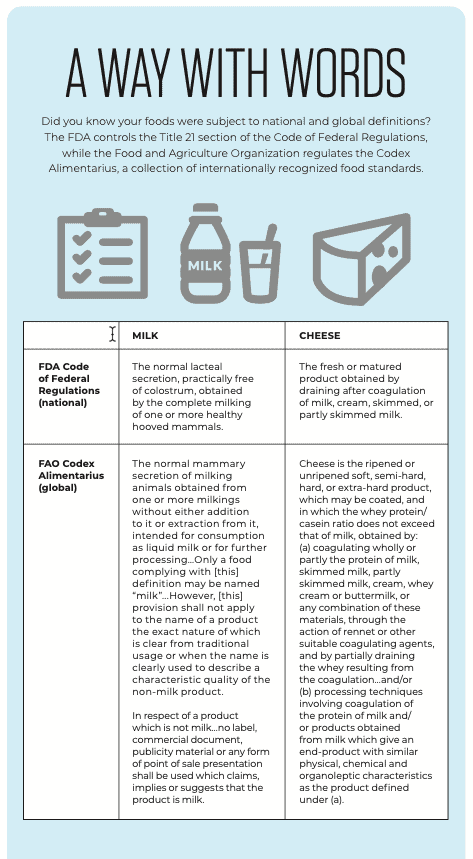

Vegan “cheese” is a bit of a sore subject. In 2019, the American Cheese Society filed comment with the Food and Drug Administration requesting that the words “cheese” and “milk” be reserved for animal products in order to not mislead consumers, a position they stand by today. To counter this, vegan advocates have invoked items like peanut butter and coconut milk to demonstrate that consumers aren’t so easily fooled. The debates get heated, and mud is often slung— earlier this year, New York City vegan mayor Eric Adams referred to cheese as being as addictive as heroin.

“Essentially, ‘cheese’ is a preserving technique,” says Bo Babaki of Philadelphia-based vegan creamery Conscious Cultures (now Bandit, see note). “If you’re taking the same technique and applying it to a different substrate, to me that’s cheese.” Babaki’s cashew milk wheels are crafted with traditional cultures, enzymes, and aging, and they look a heck of a lot like the real thing—in fact, one of his long-term goals is to enter them in (and win) a dairy cheese competition. For now, though, he avoids putting the word “cheese” on his labels, using descriptors like “ash-ripened” or “bloomy rind” to clue customers in.

Yoav Perry, fellow Philly resident and founder of Perrystead Dairy, is a friend and adviser to Babaki, but he disagrees with him on naming. A major figure in the artisan cheese community, Perry straddles a unique line—he has consulted for vegan cheesemakers, though he says he’d never regard their wares as “cheese.”

“The word ‘cheese’ defines a huge variety of products, the only connection among them is that they are made from mammal’s milk,” Perry says. “The vegan alternative has zero connection to this concept.” Perry thinks that as vegan makers forge their own path, pitting the two against each other will eventually become irrelevant. But in an industry where name control is everything, that moment feels far away.

“I personally have an issue with the use of the word ‘cheese,’” says Shannon Tallman, a Whole Foods cheese buyer in Portland, Maine. “It’s the same issue I have with cheesemakers calling their cheeses things that they’re obviously not, like Gruyère.” Perry echoes this: “It’s absurd that I am not allowed to call my product ‘cream cheese’ if it wasn’t tested for a minimal amount of butterfat, but vegan producers can call their nut paste ‘cream cheese.’”

The FDA currently has no standards of identity for plant-based cheeses but says it’s studying the issue. Meanwhile, vegan makers are already finding workarounds via label constructs like “just like FETA” or “SMOKED GOUDA STYLE” in big letters, with “cheese alternative” in smaller font.

At Tallman’s store, vegan dairy products are kept in the Grocery department rather than at the specialty cheese counter, and she says the future of that placement really depends on how artisanal vegan wheels become. They’re making headway, as Babaki exemplifies, but vegan brie doesn’t exactly disrupt the factory farming model.

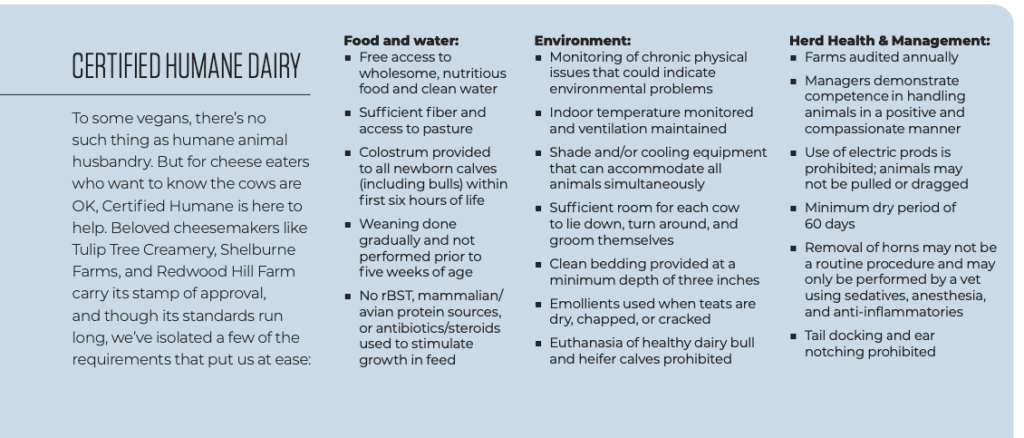

“CAFOs (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations) are not the milk source of specialty cheese, small family farmers are,” says Perry, “many of whom go to great lengths to ensure healthy regenerative soil and exemplary animal husbandry.” Most of the operations covered in this magazine fit that description, with several carrying Certified HumaneR status and others enacting carbon drawdown plans. A prime example is Shelburne Farms in Vermont, where historic land preservation is part of their business model. On top of sequestering tons of carbon in their landscape, they also maintain grasslands which their cows share with nesting bobolink and sparrow populations.

Vegan alternatives to industrial commodity cheese (think: shredded mozzarella and cheddar) could have a wider effect than artisan analogs, especially if used in school cafeterias or fast-food chains. But even in that scenario, vegan brie may play an important role.

In New York City’s Essex Market, the entire case at Michaela Grob’s cheese shop Riverdel is vegan. And while most of her customers are, too, she says about a third come in because they’re lactose intolerant, avoiding cheese for other reasons, or just plain curious. “A lot of people realize they don’t digest dairy well but still want their cheese,” she says. Plant-based artisan options may be bringing folks who’ve avoided dairy for years back to the counter— something the whole industry can get excited about.

Farm to Table

“Right now, our goal is to share the stage with animal milk, butter, and cheese,” says Miyoko Schinner, founder of dairy-free brand Miyoko’s Creamery, which occupies shelf space in roughly 30,000 retailers around the country. Schinner, who has “Phenomenally Vegan” tattooed on her right bicep, is just as passionate about transforming animal husbandry as she is about bringing dairy farmers along for the ride.

“Most small stakeholder farmers are third-, fourth-generation good people just working the land and doing what they’ve always done to create food for their communities,” says Schinner. “Many are getting squeezed out and are barely scraping by.” She recalled one farmer she met when picking up a calf from him to bring back to her Rancho Compasión animal sanctuary. The 75-year-old was shutting down operations because he wasn’t making money, and his devastation broke Schinner’s heart. Schinner’s team began research in 2019 that would eventually become Dairy Farm Transition (DFT), an organization that supports dairy farmers’ exploration of alternative crops.

“As a company paving the way for a new future of cheesemaking from plant milks, we thought it would be beautiful to help one of those farmers transition to growing crops for our product line,” she says. DFT is currently compiling a package that will include transitional income, a business coaching toolkit, and hands-on training to assist farmers interested in shifting from cows to crops. And some are already making the shift without support—in 2017, long-time New York dairy Elmhurst 1925 transitioned from cow to retail nut milks. “We want dairy farmers to see plant-milk cheese as an opportunity,” Schinner says, “not a threat.”

Yet there’s a limit to what farmers can grow stateside. Miyoko’s cheeses are made with cashews and coconuts, while others are made with almonds and soy. The origins of these crops— and what would happen to them if vegan cheese demand were to skyrocket—is a common talking point for dairy cheesemakers.

“Trucking billions of bees from New York to California to pollinate water-guzzling almonds during a drought, deforestation of rainforests for expanded soybean demand, the child labor horrors without which the cashew trade would collapse, these are not my ideas of ethics and sustainability,” says Yoav Perry. “If you really want the vegan product for its supposed environmental benefits, the soil must be organic, but what are organic fertilizers? Cow manure, fish bone meal, worm castings, animal products. It’s a spectacular irony, the crops that make ethical vegan animal alternatives are carnivores, while milking animals are strictly vegan.”

Schinner sources her cashews from a sustainable farm in Vietnam, and a third-party life-cycle analysis reported that her products release 98 percent lower greenhouse gas emissions than cheese. “It seems counterintuitive,” she says, “but transportation is actually a very small part of a food’s GHG footprint.” Babaki also sources his cashews from Vietnam (as well as Ghana, Ivory Coast, and India), through a company called Red River Foods. He says that although his supplier uses all the right words on their website, the claims are difficult to verify from afar. “It’s really hard when you’re sourcing things that aren’t local,” he says.

That word, “local,” feels indistinguishable from artisan cheese. The twenty-first-century interest in farm-to-table eating has helped small farmers stay afloat by securing additional income from ecotourism while providing transparency to customers. When I asked Schinner about “farmstead” vegan cheese, she said she’d have to move to the rainforest to make that. But she’s currently experimenting with US-grown pumpkin and watermelon seeds, so she didn’t rule the idea out.

The Future of Food

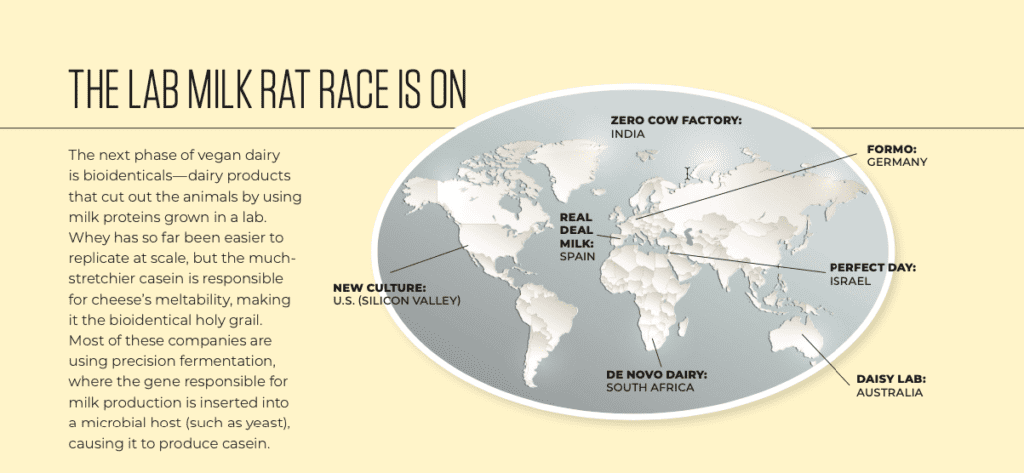

We may not have to worry about the provenance of cashews for long. Just as MorningStar walked so Impossible could run, vegan cheese is making the leap to bioidenticals— cheeses that look, taste, and (perhaps most importantly) stretch like the real thing. The stretch in a cheese pull is created by casein, a protein that scientists have recently discovered how to grow in a lab using a synthetic biology technique called precision fermentation.

But will the artisan industry go for lab-grown cheese? Cheese counters often refrain from stocking vegan cheeses— not out of a loyalty to dairy, but because of the processing they undergo. Neither plant-based cheeses nor processed dairy products are allowed to compete at the American Cheese Society Judging and Competition (bad news for Bo Babaki).

Are processed products inherently bad for us, or are we just being snobs? Leslie Murray, a registered dietician for the Duke University Health System, says it all depends on your nutritional goals. “Vegan cheese is a processed food,” she says, “meaning it contains saturated fat, sodium, preservatives, and color additives.” But she notes that plant-based and dairy cheese each have their benefits and downfalls: Vegan cheese is good for those with dairy allergies, but it doesn’t do much for the soy- or nut-allergic. And though vegan cheese may be lower in cholesterol, dairy cheese is much higher in protein and calcium. In the end, it’s a choice a person must make based on their own needs—and their own ethics.

“Consumers are becoming increasingly aware of the environmental impacts of animal agriculture, as well as the condition of factory farms,” says Schinner. “Younger people, especially Gen Zers, feel empowered to affect change through their food choices.” This condition of youth is not unique to 2022, and the vegan movement has failed to go mainstream before—the 1960s picked up where Kellogg and Sinclair left off, but even the free love generation had to grow up eventually. The trick seems to be creating a culture that is not fringe, where vegan products are seen as another option rather than a substitute. Embracing the best of both vegan and dairy could lead us to a sustainable and diversified global food system, the need for which gets louder every day.

“I don’t think this is a fad that is going away,” says Schinner. “It is, in fact, a growing movement globally, and the pace will only pick up.”

Editor’s note: Shortly after this story was published, Conscious Cultures rebranded as Bandit.