When I spoke to Mateo Kehler, he was a floating head against a Zoom background. All around him was a night skylit by a blue cheese moon: the painting on his milking barn at Jasper Hill Farm. This mural is a familiar sight to cheese industry folks, and its comforting presence has accompanied Kehler into round-the-clock meetings since the start of the pandemic.

Jasper Hill made national headlines in the spring for selling off its entire herd of Ayrshire cows, a decision made so the creamery could continue buying milk from the farms that surround them in Greensboro, Vermont. They’re currently paying more than double the commodity market rate for milk, trying to keep their community alive amid what Kehler calls an existential moment for the cheese world.

Mateo Kehler, Jasper Hill Farm

Over the past 10 months, a pandemic that has blindsided the nation has not spared a dairy industry already hanging on by its teeth. In March and early April, some farmers dumped excess milk and culled herds to deal with the drop in sales. “Supply exceeded demand by at least 10 percent in the early days,” says Theresa Sweeney-Murphy with the National Milk Producers Federation. This was in large part due to the closure of restaurants and schools, which typically absorb half the milk produced in the US. With this income evaporated, farmers and makers were left scrambling to reinvent their businesses overnight.

—

The first confirmed case of the coronavirus was reported in a suburb outside Seattle on January 21, 2020, and the first deaths not long after.

“When Seattle started getting hit hard by COVID, we decided to stock up on our PPE, but we honestly didn’t think we’d be affected,” says Marci Shuman of Cascadia Creamery in Trout Lake, Washington. When Governor Jay Inslee mandated a statewide shutdown, Shuman and her partner John were shell-shocked. “We didn’t realize how much of our sales went to restaurants and food service.”

I heard this sentiment echoed industry-wide. “There’s nothing like every restaurant in the world shutting down to help you understand how your market is segmented,” says Kehler, who lost 40 percent of his business when restaurants closed. Cascadia quickly cut production and laid off their staff. The Shumans hunkered down, and six quiet weeks passed without an order.

As news of Washington’s fate spread across the nation, panic set in—and with it, panic buying. In Brooklyn, New York, cheese shop Greene Grape Provisions had to rent out fridge space to store the eggs and milk they were ordering to meet demand. But while basics like flour and yeast sold out, washed rinds and funky tommes weren’t exactly flying out the door.

“There seems to be a general misunderstanding that anyone in food production is doing well because the grocery stores are so overwhelmed,” says Lindsay Slevin, president of the Washington State Cheesemakers Association. To get farmstead cheese into more people’s carts, WASCA applied pressure to retailers, and the stores were responsive—local chains offered buy-one-get-one local cheeses and expedited the often-tedious wholesale onboarding process. National chains soon joined them, and the Oregon Cheese Guild followed WASCA’s lead.

Lindsay Slevin and Her Family of Twin Sisters Creamery

But even with smoother onboarding available, many cheesemakers are still excluded from chain retail by packaging demands. National grocers rarely buy or sell cheese cut to order from whole wheels, which leaves a lot of farmstead makers on the outside. Kehler bought an exact-weight cheese-cutting machine in mid-March and will start selling pouches of grated cheese soon, but the packaging dilemma is a major barrier for the Shumans. Being certified organic, Cascadia can’t outsource packaging to third party, and it doesn’t help that these cost-prohibitive updates are needed at a time of record-low sales. The Shumans have applied for government loans and grants, but the process is slow. In the meantime, they’re leaning into online orders to sustain them.

—

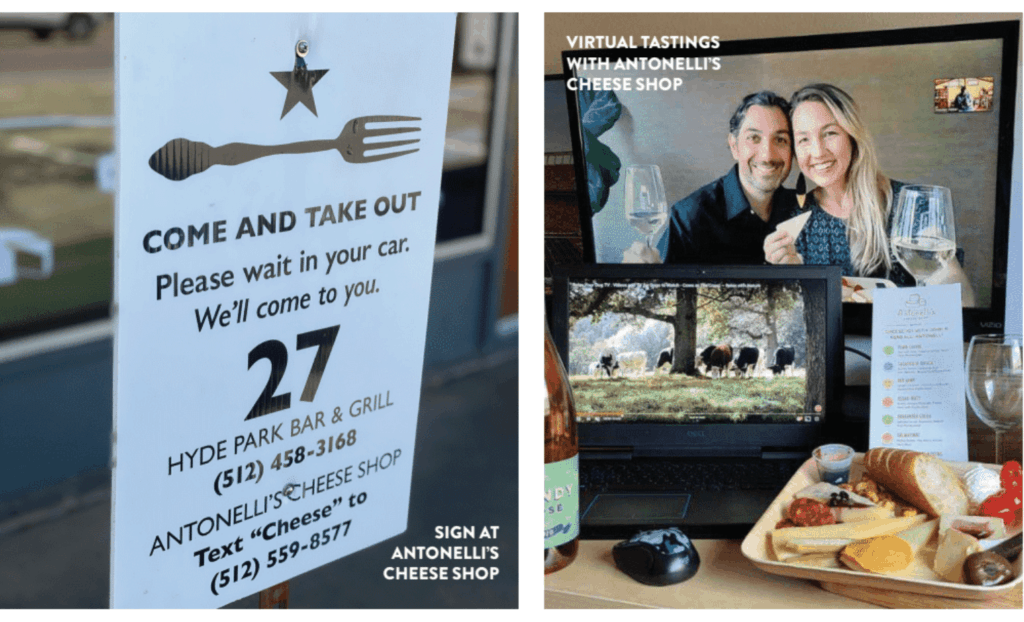

“We like to say we changed more in 10 days than we had in 10 years of business,” says Kendall Antonelli, co-owner of Antonelli’s Cheese Shop in Austin, Texas. She’s been renting extra fridge space for the ice packs needed to fulfill her mail orders this year; in the midst of a recession, she’s hiring to meet online demand, as is Jasper Hill. “Turns out shipping pallets of cheese out into the world is fairly straightforward compared to cutting and wrapping and getting all those little pieces of cheese in a box,” says Kehler. “Feels like we’re working for UPS some days.”

Nowhere is the e-commerce pivot more apparent than with Victory Cheese, a volunteer organization that facilitates the distribution of domestic cheese boxes curated by makers, mongers, chefs, and farmers. “Our first meetings were in early April and I think for a lot of us, it felt like a lifeline,” says Victory Cheese co-founder Molly Browne. These virtual meetings brought together heavy hitters like Greg O’Neill, Carlos Yescas, Janet Fletcher, Jeremy Stevenson, Stephanie Skinner (co-founder of culture) and Anne Saxelby—the cheese-world equivalent of a Vanity Fair roundtable. The fledgling organization met every Monday, and the calls became a linchpin in each member’s sanity. Uplands Cheese Company in Dodgeville, Wisconsin was one of the first vendors to come online, and sold 400 of its Badger-state boxes in just a few weeks. Since then, Rick Bayless, Dan Barber, and Marcus Samuelsson have created boxes, and retailers across the country (including Whole Foods) sell them online and in stores.

“It makes my heart swell when I think of all the hard work and creativity that the Victory Cheese folks put in to support small cheese producers,” says Marci Shuman, whose sales picked back up in May due to inclusion in a Victory box.

Victory also helped Sweet Grass Dairy in Georgia stave off an untimely fate. “Our accountant looked at our numbers at the end of April and said that if those trends continued, we would only be able to stay in business for three to six months,” says Sweet Grass co-owner Jessica Little. “It felt like a terminal diagnosis.” Since then, Little has put together a Victory box with fellow southern cheesemakers Boxcarr Handmade Cheese, Goat Lady Dairy, and Sequatchie Cove Creamery.

Forming Green Hill Cheese at Sweet Grass Dairy

It should come as no surprise that a community accustomed to gathering at conferences and food shows would have trouble spending a year apart. The American Cheese Society hosted a spate of virtual programming in lieu of their July conference, and the Cheesemonger Invitational was reborn as the virtual Flattening the Curd event in October. You’ll find these tales of resilience in every corner of the industry—but unfortunately, resourcefulness isn’t always enough.

—

When Allison Lakin started Lakin’s Gorges Cheese in Waldoboro, Maine, in 2011, she geared it toward wholesale, with restaurants her primary customers.

“The week of March 16 it became clear that everything was about to change,”says Lakin, who lost 85 percent of her business that month. She pivoted her model right away, extending farm store hours and introducing handmade pastas and cannoli. As Maine warmed up, she guided tastings for small groups through the screen of her summer house and converted her supper series, normally held at a 20-person table under a grape arbor, into Cowside Dining, with tables throughout the pasture and vintage picnic baskets full of food.

Seeking to bring more customers to the farm and help her neighbors, Lakin created a Google Sheet of food producers, updated regularly to reflect availability and pandemic protocols. When she asked the University of Maine Cooperative Extension office to help promote it, they did her one better, converting the database into an interactive map. To date, it has 475 listings and has been viewed over 1 million times.

She also created the Long Cove Farmer’s Market, which boosted sales at first. But in the fall, these markets dropped off a cliff. “The plan had been to run until Oct. 12, but the visitors declined from 200 to 60 to 10,” says Lakin. Her experience with e-commerce mirrored this—a spring boom followed by crickets. She’s installing a wood stove and buying heaters to keep dinners going all year, figuring out how to offer virtual tastings, and looking into creating a Victory box, but feels frustrated by reports of cheesemakers having their biggest online sales ever. “I keep adapting, but at this point I’m wondering if we can survive,”she says. “I’d really like one less thing to be hard.”

There’s an article like this about every industry now, and each comes with its high and low points. In the cheese world—where cash flow follows a seasonal rhythm and aging decisions must be made months ahead—the unpredictability of this moment will be felt for years to come. Melancholy tinged many of my conversations as the old ways receded in the rearview, but that nostalgia was accompanied by something I didn’t expect: dogged optimism, and a little pride.

In just a few short months, an industry with its roots in tradition has proven itself flexible, modern, open to embracing whatever it takes to stay alive—be it grated cheese or grocery chain lobbying, dry ice or Zoom. Whiplash brought with it fresh perspective, and most businesses have had no choice but to reevaluate…well, everything.

Over in Vermont, Mateo Kehler’s team spent the summer scheming. They’re tearing down their milking barn to make room for a new building, and planning to not only bring cows back, but double the herd size. The blue cheese moon will set for good, but Kehler is inviting the muralist who painted it back to create something twice as big on the new barn. “It’s sad to see something go,” Kehler says, “but hopefully what we build on top of it will be even better.”

FARM AID

—

Collaboration and innovation got cheesemakers far this year, but as sales bottomed out, nothing helped quite like cash. In 2020, American dairy farmers have received upwards of a billion dollars in federal assistance. These are a few of the programs giving them a leg up:

CORONAVIRUS FOOD ASSISTANCE PROGRAM: Funded through the CARES Act, CFAP earmarked $16 billion for direct payments to farmers. At press time, dairy farmers had received $2.6 billion through this USDA program.

FARMERS TO FAMILIES FOOD BOX PROGRAM: Under the umbrella of CFAP, the federal government purchased approximately $600 million in dairy products from struggling farmers this year. This dairy is delivered to food banks and nonprofits that assist Americans experiencing food insecurity.

PAYCHECK PROTECTION PROGRAM: The CARES Act allocated $349 billion to the PPP, which offers loans up to $10 million. But according to the National Milk Producers Federation, a requirement that sole-proprietor farms apply using their 2019 net profit as a benchmark has complicated access—for many farms, that number is zero.

ECONOMIC INJURY DISASTER LOAN: Offered through the Small Business Administration, the EIDL is offered as either a forgivable grant of up to $10,000 (no longer available), or a low-interest loan of up to $150,000. Over $191 billion has been approved so far.

STATE GRANTS: Several cheesemakers availed themselves of state-level aid, too. Cascadia, for example, received a Working Washington Emergency Grant. Over in Pennsylvania, the state’s $5 million Dairy Investment Program can help farmers revamp marketing or business plans.

THE SHIFTING COUNTER

—

One breed of essential worker has never been far from my mind this year, and that is the food retailer. Grocers remained open this spring, dealing with record business while adjusting to new norms every day. Here are two dispatches from their front lines:

Emilia D’Albero

Cheese department manager: Greene Grape Provisions, Brooklyn, NY

Emilia D’Albero recalls walking past refrigerated trucks holding morgue overflow and riding empty subway cars reeking of bleach to get to work last spring. “The physical and emotional toll the pandemic took on us as a staff is difficult to put into words,” she says. At one point, D’Albero was working between 60 and 80 hours a week. “The backs of our ears literally bled from wearing the masks for so many hours…I started each day with a coffee and a panic attack.”

Nearly a year in, D’Albero is pushing domestic cheeses and keeping wheels moving via her grab-and-go case, but not offering samples: “I’ve been telling customers if they don’t love the cheese we recommend, they can just bring it back and we’ll find them something different.”

Maura Rice

Cheese buyer: France 44 Cheese Shop, Minneapolis, MN

When things got serious in Minneapolis, France 44 emailed their customers a plea for help—and got over 250 orders. “I was in a blackout for most of that pickup day,” says Maura Rice, whose staff immediately started pulling triple duty as mongers, bouncers, and order runners. The store stopped taking cash and started handing out masks.

They also ceased sampling, which, according to Rice, has its benefits. “It’s undeniably easier to sell a cheese based solely on your pitch,” she says. With so much digital content abounding, she’s also finding it easier to learn about the makers she represents. “I have never felt more empowered to take risks with my cheese buying. I really believe at this point we could sell anything.”