Photographed by Nina Gallant | Styled by Elle Simone Scott

Buffalo milk cheeses make me feel the way I do after throwing back an oyster—which is to say, like I just dove off a salt-stained dock into the Atlantic Ocean. I’m refreshed, invigorated, awake, alive. There’s something almost hydrating about them. The stark white paste feels pure as the driven snow. It brings the word “clean” to mind.

This is ironic, considering water buffalo spend most of their time in the mud. The animals got their name from all the time they spend submerged in water, which they do to regulate their body temperature as they lack sweat glands. They even have cloven hooves to give them traction when tromping around mucky riverbeds.

If you’re having trouble picturing them, you’re not alone. Somewhere along the line, early American settlers got it in their heads to start calling bison (the wooly brown humpbacked creatures that graze our western grasslands) “buffalo,” despite having very few similarities to the black species with ram-like antlers that originated in India. This type, known as the Asian or river buffalo (not to be confused with the African buffalo—stay with me), has been around for centuries, and you’re still more likely to find cultured dairy products (think: paneer, yogurt) made of buffalo milk instead of cow’s milk in India today. How and when this species got to Italy and morphed into the mozzarella kingpin called the Mediterranean buffalo is wildly disputed, though most accounts say it happened somewhere between the second and seventh centuries and had something todo with their hardiness as draft animals. (They also eventually wound up in South America, where a fledgling buffalo milk cheese industry is on the rise today.)

Our inability to identify these creatures in a line-up has not kept food people from elevating their products to cult status. Buffalo mozzarella has been referred to as the white whale of the cheese world, and much ink has been spilled over Proustian first experiences with it and epic hunts for it. So why are these beloved cheeses so rare outside of a select few countries? Why aren’t American cheese cases full of them?

For starters, the animals get a bad rap. Many farmers and makers view the buffalo as a bit of a diva, requiring very specific conditions to release her milk. “One must learn their peculiarities, which are many,” says Bruno Gritti, who makes buffalo milk cheeses with his brother Alfio at their farm, Quattro Portoni, in northern Italy. Their animals are given access to massagers and spray showers, 15 square meters of space per head, and corridors that allow them to move freely, which can reduce stress (and don’t we know it).

The animals are also larger than cows and highly intelligent. “Any time any thought crosses your mind such as, ‘They can’t open that gate latch,’ you have to train yourself to go put a better closure,” says North Carolina buffalo farmer David DiLoreto. He keeps his animals happy by sticking to a regimen of no new people on the farm, no change in their feed, and no new noises or smells in the milking parlor.

Buf Mozzarella

Not everyone wants to take on that extra work (and cost). Here in the U.S., one of the largest buffalo dairy farms is actually on a prison complex in Colorado, where the additional effort is taken on by a literally captive (and low-cost) workforce. That said, some farmers are willing to take their chances on these animals of ill repute. “Water buffalo are actually quite calm,” says Alejandro Gomez Torres, founder of Colombian buffalo cheese producer Buf Creamery. “They just need a defined routine with a lot of patience.” At Buf, that still means a relaxing cool shower before milking, calves kept by their mother’s side during milking, and the freedom to dine on verdant Andean grassland year-round.

Whether or not a would-be cheesemaker considers these peculiarities prohibitive to a business model, there’s another problem: buffalo produce a lot less milk—only six liters a day, relative to the average dairy cow’s 30. Buffalo also have a longer gestation period and a longer dry period. More milk solids per liter of milk help to balance this, but it doesn’t totally offset the discrepancy. “Although the yield, cheese-wise, of buffalo milk may get to 20 percent vs. 12 percent of cheese made from cow’s milk, the costs of raw materials and what it takes to raise a buffalo is still much greater,” says Bruno.

DiLoreto echoed this. “Buffalo produce the volume of a goat and eat like a cow,” he says. The milk buffalo do produce, though, is liquid gold. Relative to cow’s milk, it has 40 percent less cholesterol but more protein, fat, calcium, iron, magnesium, phosphorous, potassium, and Vitamins A, B, and E. It also may be easier for lactose intolerant people to digest. And according to Alfio, who manages the animals at Quattro Portoni, buffalo contract fewer diseases, have a lower incidence of lameness, and are able to undergo about twice the number of lactations than the average dairy cow. All that’s to say nothing of the flavor. In Italy, balls of fresh buffalo milk cheeses are often served still warm from being stretched, a multi-sensory experience that will haunt your dreams. But therein lies another layer of difficulty—fresh buffalo milk cheeses are highly perishable. To really experience their unique softness and sour tang, they should be eaten within a week, which has no doubt played into the black-market aura that surrounds them. Your ability to get a fresh ball often depends on your proximity to the nearest buffalo farm.

In Colombia, Buf has devised a workaround: Their balls of burrata and mozzarella hitch a ride on the refrigerated trucks and planes of their country’s fresh flower industry. (It also doesn’t hurt that they’re much closer to the U.S. market than Europe.)

So how can Italian makers get around the perishability issue? Age. Bruno and Alfio grew up on a cow farm, but when it was their turn to inherit the family business, they wanted to do something different. They decided to raise buffalo—not to make the fresh mozzarella popular further south in Campania, but to create aged cheeses linked to the Lombardian tradition, like buffalo Taleggio and pungent blues. “I told my idea to make aged cheeses using buffalo milk to a friend, one of the most important farmers in the region,” recalls Bruno. “He responded, ‘Why should a consumer buy buffalo milk cheese that costs much more money to the same one made from cow’s milk?’”

Their friends thought they were crazy, but they knew there was a big market beyond Italy and started attending local trade shows. “We always aroused curiosity since this was the first aged cheese made 100 percent from buffalo milk,” says Bruno. At the 2007 TUTTO FOOD show in Milan, one curious scouter was Michele Buster of Forever Cheese. She took one bite of their Blu di Bufala and became Quattro Portoni’s first U.S. importer.

“It has been a great experience,” says Buster. “A challenging one due to the costs, however rewarding as we’re working with something so delicious and groundbreaking in nature.”

Crown Finish Caves Bufarolo

Though few makers have attempted aged buffalo milk cheese in the States, affineurs at Crown Finish Caves in Brooklyn, New York, are making magic out of green (young) wheels shipped to them from Quattro Portoni. Washed in a Brooklyn beer and aged in old lagering tunnels that run beneath the city, their resulting Bufarolo is a CFC staff favorite that’s broadening the appeal of buffalo milk cheeses stateside. CFC sales manager Caroline Hesse says buffalo milk, which she describes as “effervescent,” has become her favorite of all the cheesemaking milks. “I think cow’s milk cheeses are very much the default of our dairy landscape,” she says, “Buffalo milk cheeses are anything but default.”

Tasting Notes

FADING D FARMS MOZZARELLA (North Carolina, U.S.)

On a fated trip to Italy, Faythe and David DiLoreto became so obsessed with buffalo mozzarella, they had no choice but to recreate it when they got back home. Many training courses and research trips later, they finally coaxed a lush and supple mozzarella out of their pasture-raised buffalo that was worthy of their Italian memories.

CROWN FINISH CAVES BUFAROLO (Bergamo, Italy/New York, U.S.)

Washed in beer from neighboring brewery Transmitter, this Taleggio-style square is firmer and chalkier than the Italian classic, with sour funk at the rind and a paste that is both crumbly and somehow thirst-quenching. Approachable yet utterly unique, this one is hard to stop eating.

BUF MOZZARELLA (El Rosal, Colombia)

Looking to understand the difference between a cow’s milk mozzarella and a buffalo’s? Let this pillowy-soft Andean offering, made from the milk of buffalo grazing wild mountain grasses at 9,000 feet, be your guide. One bite of the stuff and you’ll no longer be able to understand how it ever held its round shape—it becomes silk beneath your spoon.

DECA & OTTO BURRATA (Northern Colombia)

Happy buffalo are the priority at Deca & Otto, a Colombian company named after their first buffalo and the bird that regularly perches on her head. Their 100 percent grass-fed burrata feels like drinking (or maybe diving headfirst into) a glass of raw milk. We didn’t know it was possible to make burrata MORE indulgent, but apparently it’s easy: just add buffalo.

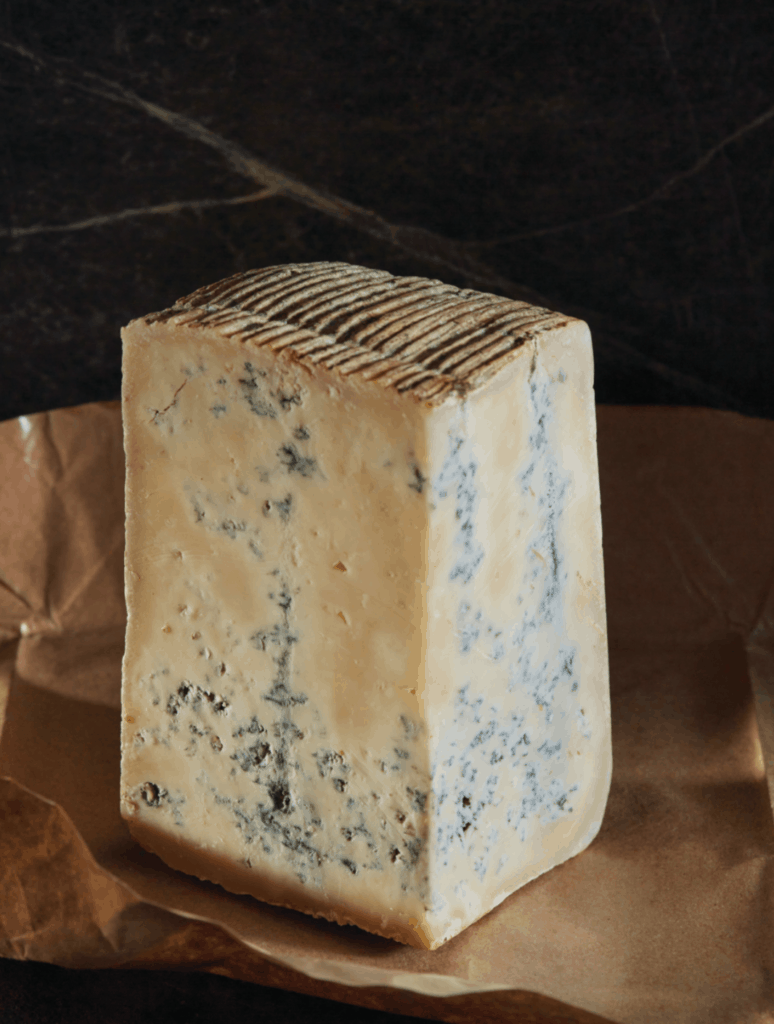

QUATTRO PORTONI BLU DI BUFALA (Bergamo, Italy)

It’s hard to choose from QP’s range of a dozen buffalo milk cheeses—if you see their Moringhello or Porta Rocca anywhere, be sure to snag ‘em. But this is the one that started it all, and it’s easy to see why. With a sweet, mild buffalo milk paste, the mold’s mossy funk gets to be the star here. Also unmissable is QP’s Surfin’ Blu—Blu di Bufala washed in Italy’s Toccalmatto Brewery Surfing Hop beer.

RIVERINE RANCH FARMSTEAD AGED (New Jersey, U.S.)

More earthy and nutty than anything else on this list, this wedge is a great table cheese reminiscent of a French tomme. Made on a ranch that also produces killer buffalo milk labneh, paneer, and yogurt, this cheese proves that there’s a world beyond mozzarella for American buffalo milk cheesemakers.

LA CASERA CAMEMBERT DI BUFALA (Verbania, Italy)

I will never forget the first time I cut into this wheel’s unassuming bloomy rind. The white velvet that oozed out is burned onto my retinas, its milky and delicate sweetness a tattoo on my tongue. If you come across this cheese, you’ll need nothing more than a loaf of crusty bread—hell, you may only need a spoon.

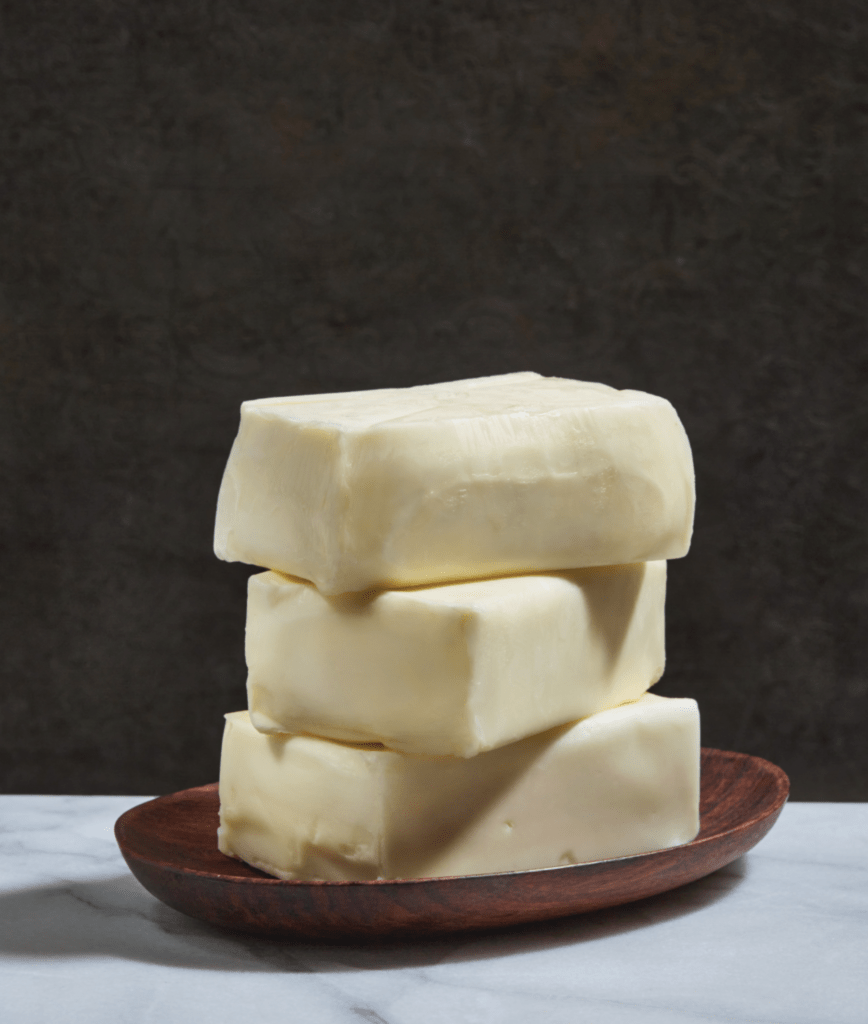

DELITIA WATER BUFFALO BUTTER (Lazio, Italy)

Ok, so, not technically a cheese, but this is nearly a foregone conclusion for a milk type known for its abundance of fat. When you peel back the parchment on this glistening block of porcelain butter crafted in the Italian province of Latina, you’ll be tempted to go at it like carnival fudge. I’d tell you not to, except…that’s exactly what I did. However you use this stuff, just make sure you savor it.