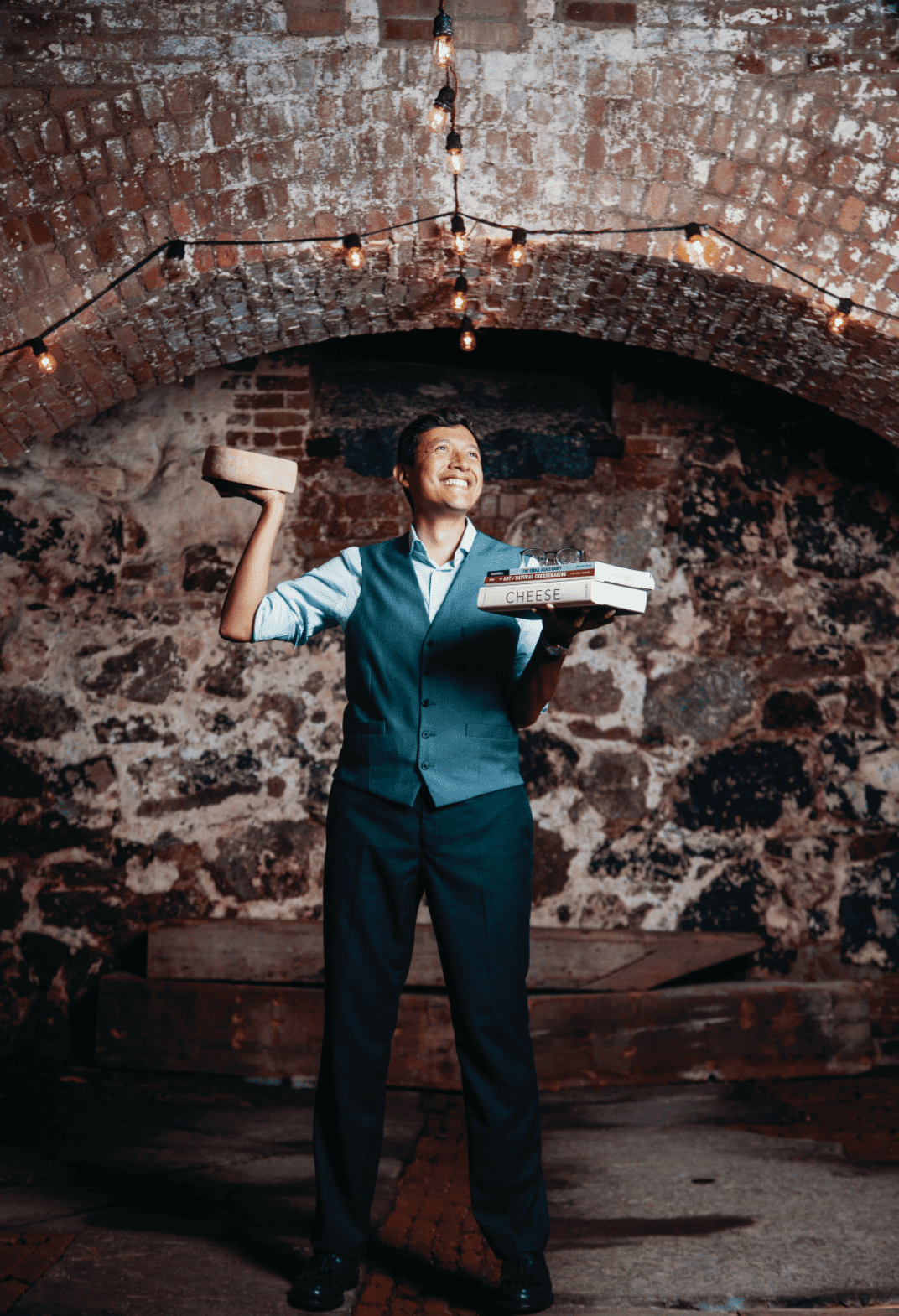

Photograph by Gomez Carbajal

The cheese world is lucky to have Carlos Yescas. During a career that began in diplomacy at the United Nations Development Program and progressed into a job at the Mexican Consulate in Boston, Yescas found his way to artisan cheese and has been advocating for it ever since. In 2009, he co-founded the first artisan cheese distributor in Mexico (Lactography) with his family, then created the LACTEO Network to educate and promote Latin American cheesemakers in 2019. He’s also served as a judge at the World Cheese Awards and taught courses on food law at New York University, and currently stumps for raw milk in his role as Program Director for the Oldways Cheese Coalition. Ever helpful, Yescas took some time to chat with us about how to make the cheese world work better for everyone.

culture: You’ve lived and worked all over the world—Ireland, France, China, Mexico, and here in the U.S. in NYC, Ann Arbor, and now Boston, to name just a few places! Where did you grow up, and where do you call home now?

CARLOS YESCAS: I was born in Mexico City and grew up between the city and a small town called Cocoyoc in the state of Morelos. I still don’t feel settled in a place as home, just yet. My husband and I are nomads, and we hope one day to settle down some place where we won’t ever need a car and with a nice cheese shop close by. I would love to live in Europe again. The one thing I have missed most during COVID-19 is street food, so I hope to find a place where markets are available.

You started your career at the United Nations—how did this morph into cheese advocacy?

CY: I started with a deep care for rural communities, concern for the environment, and my own experience as an immigrant. Growing up in Mexico […] many rural areas were being emptied by immigration to the U.S. and Canada. On the other hand, those left behind were suffering more and more from low agricultural yields and increasing use of pesticides. My father worked in agricultural development for the Mexican government, so these were topics I would hear about at home.

Later, I came to the U.S. for college. My first job after graduating involved working with migrant workers in New England. Through this, I realized how food production was interconnected with everything. I studied for a master’s degree in Human Rights Law in Ireland and then worked at the UN in New York on migration issues. There, I saw the need for global policy, but also for work on the ground. Cheese had also already become something more than a hobby, and I was visiting cheese farms in Mexico and helping the government of Chiapas to apply for a Denomination of Origin for a local cheese. (We didn’t get it.) Meanwhile, my family had started our company in Mexico City selling cheese, with an ethos of helping rural communities thrive. My sister stayed in Mexico to take care of the business, and my husband and I returned to the U.S. Eventually I landed the job at Oldways, which tied everything together.

The artisan cheese industry has a history of leaning very white and western, with cheese cases typically full of French, Italian, Spanish, and North American wheels. Why do you think the industry has been resistant to other cultures? And do you think that’s changing?

CY: English, Swiss, French, Greek, and Italian imports have long benefited from immigrants from those countries who settled in the U.S. They brought with them expertise to make cheese, but they also wanted original products from home, so strong trading connections were established […] Other cultures have brought other foods, but not as much dairy. For example, a number of Polish and Portuguese immigrants run delis in Northeastern cities, but we still don’t know many of their cheeses. Meanwhile, Latin America has produced dairy products of quality for a long time, but strict regulations prohibit much of it from crossing borders […] There are immigrants from Mexico and El Salvador domestically making products in the U.S. for local markets, often exclusively sold in Hispanic stores with little cross-over to mainstream markets.

Second, I think the gourmet industry that you are referring to has benefited from a foodie culture and discourse, which propels some products and techniques to prominence. This industry itself is still mostly white, and it serves affluent consumers. There is a growing awareness of blind spots in the industry, but I don’t think anything is changing yet in a substantial way. We are at a stage where people are focused on representation. Along with the larger food industry, it won’t become fundamentally more equitable until people start changing the structures that have allowed for disenfranchisement in the first place.

What are some ways the artisan cheese industry could better advocate for cheesemakers from minority communities?

CY: Increased transparency in pricing from the maker, to the distributor, to the retailer, to the final consumer would help small producers and workers in their plants. Fairer pricing and compensation would start to open a space for minoritized communities to get a footing in our industry […] For [these] communities, the barriers to entry are bigger and enforced by the market as well as the government. They are the result of discriminatory policies and dynamics that target Black Americans and are now also used to disenfranchise Hispanic migrants. Minoritized communities have historically been pushed from many rural [areas]. This has created a scarcity of Indigenous and Black farmers and opened the space for white farmers to benefit from the land. This has been made worse by the lack of access to capital through bank loans, institutional support, and continued discrimination at many levels, putting people in a huge disadvantage to become farmers or cheesemakers.

People often imagine that the imbalanced demographics of groups represented in the industry is a result of individual choices and interests, but I think it is clear that it is a product of the historical structures in place. To better advocate for cheesemakers and also open more spaces for minoritized people, we need to change the rules of the current game, which could involve some type of group reparations, access to land, and training. Above all, we need to change the system in place that drives everyone away from small agricultural production and allows for large corporate farms to establish themselves and limit competition.

Photograph by Vladimir Pudovkin

You champion raw milk in your work at the Oldways Cheese Coalition. Tell me your elevator pitch on the importance of using raw milk in cheese.

CY: Diversity is good! Raw milk cheese production helps to maintain microbial diversity. When consumers buy raw milk cheese, they are saying to a producer that they appreciate this diversity. Paying a fair price for these products ensures that someone will be able to continue making them. Also, raw milk cheesemakers, for the most part, have an approach to farming that is more in following with seasons and natural cycles, plus use distribution chains that are smaller. This translates to economies that may benefit more small actors, including independent shops and farmer’s markets.

Your work must have involved a lot of travel, pre-pandemic. How have you been adapting this year? I imagine it’s a lot of time zone math!

CY: Yes! You are definitely right. I attend a lot of meetings with people around the world. Most are informal conversations, quick text chats, or short emails to understand better what is happening on the ground in farms, stores, and distribution centers. Then I try to make sense of trends and issues. During this time, Oldways has also become more active in creating and strengthening networks of like-minded people to bring new people to the conversation. We are doing this in all our programs, not only in cheese. My co-workers in the Whole Grains Council, the African Heritage and Health program, and the Mediterranean Food Alliance are part of networks that educate consumers and help producers disseminate information in many topics around healthy eating and cultural practices.

I also spend a lot of time reading to keep up to date with the advances in cheese science and finding ways to communicate with consumers in an accessible way. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to visit any farms or producers, which is an important part of understanding the ways traditional cheesemakers work. I have tried to keep connected with producers by attending online tastings.

The pandemic has forced people in all industries to re-examine how they do business. Do you think the cheese industry has been forced to adjust in ways that could be beneficial in the long run?

CY: The industry has had to figure out how to sell direct to consumer. The jury is still out whether this will be beneficial in the long run for producers. Selling online is challenging and costly, and not everyone has been successful. Plus, the environmental impact is huge. Another way the industry is changing is in how it talks to consumers. It is not clear that the average consumer understands the differences between artisanal, farmstead, and specialty cheese producers. The big players in the industry benefit from a halo effect that small producers generate. Everyone working in the industry needs to face the uneven suffering that the pandemic has caused, hitting many small producers hardest, while at the same time some of the more established companies saw a very good fourth quarter in 2020.

I’ve definitely witnessed that in my reporting this year. Are there any areas where you think cheese professionals could better help these smaller makers?

CY: I see a huge opportunity in the cheeseboards, grazing tables, and cheese experiences projects that are starting to appear everywhere in the world. These entrepreneurs, mostly white women, are using the likability of cheese on Instagram to launch very successful businesses. However, for the most part, their cheese selections consist of products easily accessible in bulk at big box stores. I think there is huge opportunity in approaching them to introduce them to better cheeses and support small businesses. Two projects that are completely different and should be watched are Immortal Milk (@_immortalmilk), run by Alisha Norris Jones in Chicago, and Queso Crísto (@quesocrístocharcuterie), created by Alexander Eason in San Diego. They both come from a cheesemonger [and] kitchen background and are crafting gorgeous cheeseboards and experiences for their customers.

MEXICAN CHEESES YOU NEED TO TRY

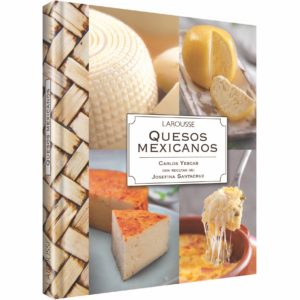

Carlos Yescas details a lot of excellent cheeses in his book, Quesos Mexicanos. We asked him to describe a few that he feels American cheese lovers should know about.

Quesillo de hebra: (a.k.a. queso Oaxaca) A pulled curd fresh cheese originally made in the state of Oaxaca, now made in many other states. It is easy to melt for quesadillas.

Queso fresco: A farmer’s cheese made using rennet and cow’s milk. It is easy to make at home and to sprinkle on top of antojitos (Mexican small dishes).

Mountain Cotija: The original cheese made in the Sierra Jalmich region, it is an umami bomb. Unfortunately, it is unavailable in the U.S., you will have to travel to Mexico to try this raw milk cheese.