This story ends with a demolished disk of cheese. Flattened by swooping baguette or scooped with a spoon until all that’s left is a withered wisp of wrinkly rind, it’s the first casualty of your cheese board every single time. But where did it begin? As in the case of most cheeses, a search for robiola’s origin story takes us back to an Old World village that seems frozen in time. Snow-capped peaks frame its green hillsides, dotted with bearded, carefully bred caprines perched on patches of terraced land.

That village is Roccaverano and the region is Piedmont: northwestern Italy’s gustatory heartland. It’s the land of white truffles, the Slow Food movement, and the Nebbiolo grape. Wedged between the Alps and the Mediterranean, Piedmont is where mountains meet hills. Agile goats have long roamed the slopes in a southeastern section called Alta Langa, grazing on herbs and shrubs, while isolated towns and villages bred distinct herds and developed eponymous cheeses.

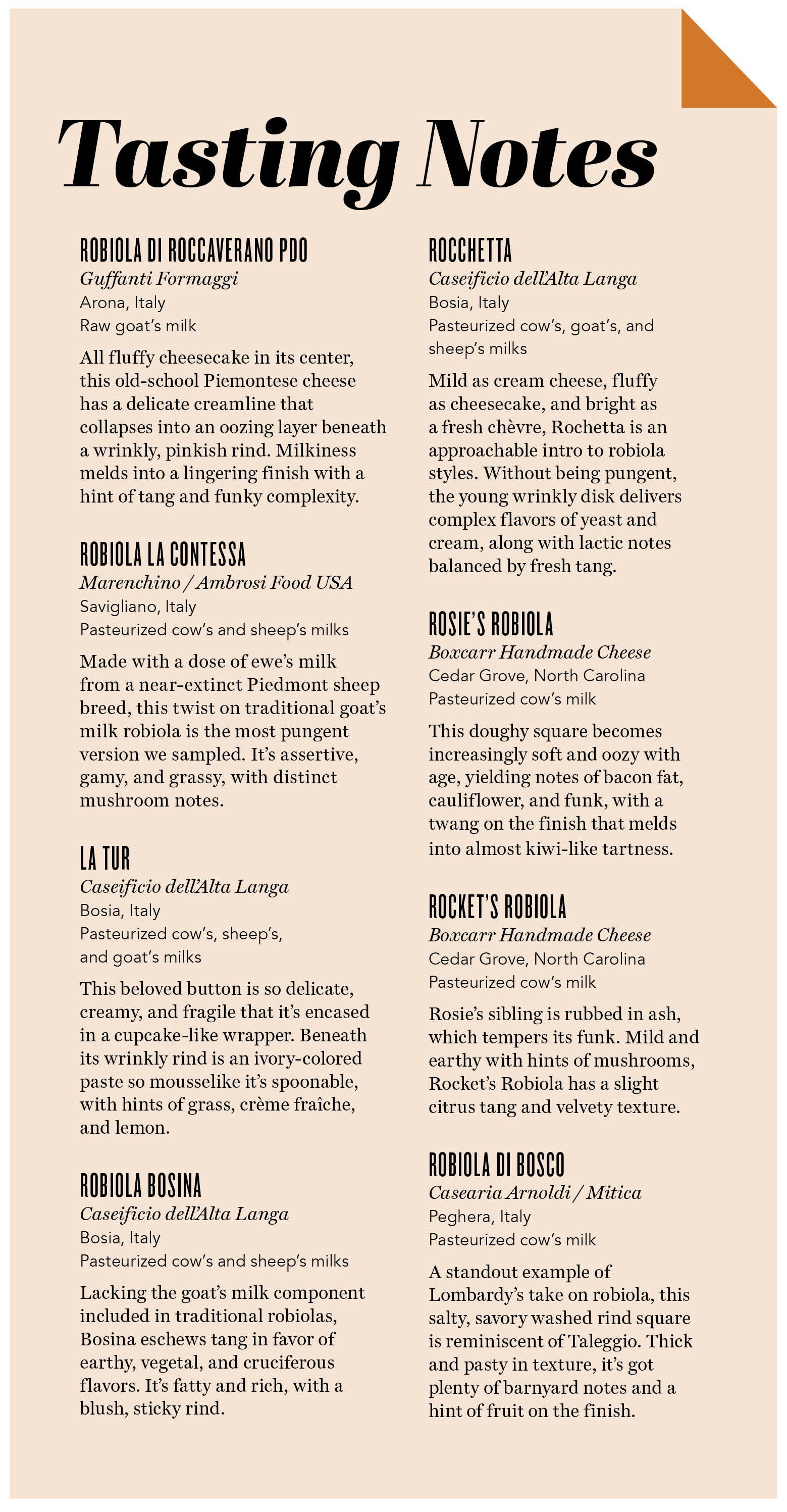

Rustic

The original Robiola di Roccaverano cheese, made from milk of the Roccaverano goat, probably came from a place called—you guessed it—Roccaverano. According to Fabrizio Garbarino, a farmer and cheesemaker from that same hilltop Piedmont village, robiola was made in Roccaverano before the Romans arrived; its origins could date back as far as 1,200 years to the time of Arab invasions, when goats were first introduced to the area.

La Tur and Robiola Bosina

In the landscape of cheese from Italy—a country famous for rock-hard grana wheels and stretched-curd pasta filatas like mozzarella and provolone—soft, bloomy-rind robiola is unique. “It’s one of the most ancient goat’s milk cheeses in Italy,” says Garbarino, who also serves as president of the Robiola di Roccaverano PDO consortium, the country’s only Protected Designation of Origin label for a goat’s milk cheese. “It’s one of the only ancient Italian cheeses made with lactic transformation,” he adds, referring to a long acidification that occurs before milk coagulates—a process more often found in the traditional goat’s milk cheeses of France.

The practice is simple and slow. Raw goat’s milk (or a mix of goat’s milk and up to 50 percent cow’s milk) is left to acidify for up to 36 hours. Bacteria—present in the raw milk and sometimes boosted with a bit of leftover whey—consume the milk’s sugars and create acid until a yogurt-y consistency develops. A small amount of animal rennet might be added to slightly firm up the curd, which is then left in a tall cylindrical mold as whey drains out slowly over two days. After salting and four subsequent days of aging, the cheese earns its PDO label and can be sold.

Young fresco versions are soft and spreadable, either rindless or with a velvety layer of mold. After 10 days of aging, disks become affinato, or “ripened.” They’re still supple and yielding in the paste, but they’ve grown a rind, its hue and texture dictated by the microbes present in the raw milk and in the environment on the farm. It’s a mix of fuzz and wrinkles; a range from bone-white to light pink-orange.

In cheese time, 10 days is not so long; most versions of Robiola di Roccaverano are essentially sold fresh. But in the United States, it’s a different story. Since it’s made with unpasteurized milk, Robiola di Roccaverano must be aged at least 60 days to be sold legally. For such a young and soft cheese, a two-month maturation is a challenge—a timeline that fundamentally changes the cheese. Garabino, one of only 17 producers of the mostly farmstead PDO cheese, sighs with exasperation—and a hint of pity—when he describes the cheese’s absence from American cheese counters. “We are very clean, and you should trust in us,” he says. “But…you are scared from the raw milk.” He’s right—and if you’ve never heard of Robiola di Roccaverano, that’s probably why.

Rochetta

Renewed

Even if you’ve never heard of Robiola di Roccaverano, you’ve probably heard of La Tur. When Piedmont-based dairy Caseificio dell’Alta Langa introduced this pasteurized twist on robiola to the US in the early 2000s, it was singular on the market; a mixed-milk, soft-ripened cheese from Italy was uncommon. The caseificio began by exporting small quantities of two other robiola-style cheeses, Rochetta (a fresh cow’s, sheep’s, and goat’s milk mix) and Robiola Bosina (a cow’s and sheep’s milk blend). Soon, distributors in the US took notice. When The Cheese Works (now known as CWI Specialty Foods) began placing big orders for Alta Langa’s super-soft, triple-milk button La Tur, it wasn’t long before the robiola-style cheese gained a cult following.

It’s not hard to understand why: with a beguiling mix of approachability and complexity, La Tur is easy to love. In her cheese column for the San Francisco Chronicle, writer Janet Fletcher dubbed it “as close to love as a cheese can get.” In a piece for Thrillist, cheese blogger Erika Kubick described it as “the cream dream.” In Bon Appétit, digital director Carey Polis called it “everything I want in a cheese.” La Tur’s mousse-like paste is as crowd-pleasing and spreadable as that of ubiquitous supermarket brie—but it lacks the brie’s chewy, obtrusive rind. Flavors are mild and creamy, yet a closer sniff reveals multi-layered notes of sour cream, butter, and mushrooms, prolonged by a fatty stratum that sticks around.

When a cheese is that likeable, selling it is a cinch. “Actually, we never relied on marketing strategies,” says Nicola Merlo, CEO of Caseificio dell’Alta Langa. “Our approach was to make customers try the products, and we relied on word of mouth.” As a result of its “unexpected success,” she adds, “La Tur started selling very well before other cheeses in the robiola category.”

Rosie’s Robiola and Rocket’s Robiola

In bringing robiola styles stateside, Alta Langa achieved a feat that was previously out of reach for the typical Piedmont producer. The caseificio is set in robiola country, just a stone’s throw from the village of Roccaverano (and it even produces a PDO version of the traditional cheese for its non-US customers), but it’s decidedly larger and more modern than the family farms that surround it.

Today the dairy exports a multitude of robiola styles in varying milk mixes and stages of maturation. According to Merlo, that variation itself riffs on regional tradition; in an area where cheese was typically made on small farms that kept a mix of animals, milk supply changed with the seasons (that’s also the reason traditional Robiola di Roccaverano PDO can be made with up to 50 percent cow’s milk).

“Farmers would mix different milks, and we wanted to reinterpret this old tradition in our cheeses,” Merlo says, adding that every milk has its own taste and character. Combining them in the right percentages brings out the best in each, without any one dominating. “The cow’s milk is the base, the sheep’s milk adds the sweetness, and the goat’s milk adds the sharpness,” she says.

Reinvented

Merlo doesn’t hesitate to use the term “robiola” to describe all her cheeses. While Robiola di Roccaverano PDO might be traced to a single goat breed and a single village, she says, “robiola” is a moniker with a much broader meaning. “It’s a general name that indicates a soft-ripened cheese which is not too aged,” she explains, adding that it may originate from the Latin term ruber (“red” or “ruddy”),a reference to the slight scarlet tinge that sometimes develops on its rind.

Following the success of cheeses like La Tur, plenty of Italian producers are now exporting soft-ripened robiola styles and experimenting with mixed-milk alchemy. Robiola La Contessa, for example, is a cow’s and sheep’s milk robiola imported by Ambrosi Food. Made at a dairy called Marenchino in the Alta Langa region, the cheese’s success has helped save the Pecora della Langa sheep from extinction. Guffanti Formaggi, an affineur based in Piedmont, ages and exports over a dozen twists on robiola—from the buffalo’s milk Robiola di Bufala, a dense, ultra-buttery disk that feels more like an Italian take on a brie or camembert, to versions wrapped in fig, cherry, chestnut, or cabbage leaves.

Robiola di Bosco

Of course, it follows that American producers are now experimenting with their own versions of the Italian cheese. Samantha Genke of North Carolina–based Boxcarr Handmade Cheese first discovered Robiola di Roccaverano PDO while traveling in Piedmont, visiting producers and staying with local friends. “We had the real thing fresh,” she says. “Actually, I don’t think we ate much else for about a month.” But after she got home, a search for the fresh Italian cheese was fruitless. “By the time we get access to robiolas herein North Carolina, they tend to be a little too ripe,” she says. “So we started making robiola because we love robiola. And we wanted robiola.”

Genke teamed up with close friend Alessandra Trompeo, a Piedmont transplant, to create an homage to the Italian cheese. Fully aware that their milk and local terroir would render this robiola very different, the duo didn’t stick to a specific recipe. The idea was to use Robiola di Roccaverano as inspiration, and just experiment. After years of testing, it’s evolved into a cow’s milk square called Rosie’s Robiola, a gorgeous cheese with a blushing, wrinkly rind and an oozing cream line that creeps towards a chalky paste. The team also makes Rocket’s Robiola, a version dusted in ash inspired by cheeses from the Loire Valley in France. Neither of these is Robiola di Roccaverano, Genke admits. They’re adaptations. “We kind of winged it. We totally Americanized it,” Genke says.

Ripened

As for the cheese that first inspired Genke, it’s not impossible to find in the United States. The family at Guffanti Formaggi ages a version of Robiola di Roccaverano PDO for two months in order to sell it in the US, slowing down the maturation process by keeping the disks at slightly cooler temperatures. Giovanni Guffanti Fiori, second-generation co-owner of the company, notes that it’s not uncommon to find Robiola di Roccaverano sold after 60 or 70 days of maturation in Italy—sometimes, it’s even aged up to a year and grated onto pasta. It’s still good, he adds, as long as “the taste fills the palate without becoming aggressive or spicy.”

Even if you’ve never met a robiola style you didn’t like, there’s something about this one that sets it apart—like the added oomph you get from a taste of cultured butter instead of a stick from the supermarket. It’s clean and creamy, with a fluffy, cheesecake-like center, but a bite yields a complex finish balanced with bitterness, tang, and funk. The rind is soft with an almost liquid cream line that readily collapses unless it’s handled with utmost gentleness.

It’s not hard to imagine why all those disks, from La Tur to Rosie’s Robiola, pay tribute to this Piedmont cheese. Maybe it’s the unpasteurized base, or the fact that this version is made with 100 percent goat’s milk. Or maybe it’s the image of the Alta Langa, with its hills and vineyards and stone villages. Either way, everything about this cheese is easy to love. Pass the spoon?

Photographed by Nina Gallant.

Styled by Chantal Lambeth.

Are the Vermont Creamery Bon Bouche & Cremont

Similar?

They’re similar in that they’re both aged creamy cheeses. But the Bon Bouche is a goat’s milk, ash-ripened cheese and Cremont is goat and cow’s milk.